Mar 02, 2010

Key Strategy Issues Vol.K289

Perspectives on deflation in Japan – 3

Lessons for the world from Japan’s experience with deflation

~Creating demand is the most pressing issue; consumptio

Japan has experienced a type of deflation that had never been seen before. As the yen appreciated to penalize Japan, wages became extremely high in relation to what workers earned in other countries. The result was strong and constant downward pressure on wages in Japan. Furthermore, Japan lost its superiority with regard to all three factors that had fueled its rapid economic growth in the past: capital, labor, and technology and access to markets. Japanese companies were subjected to powerful corrective forces that brought down wages that was a remote cause of deflation. Since these forces do not exist in the United States, there is no danger of the U.S. economy entering a period of Japanese-style deflation. But what about another type of deflation? Anti-globalists believe that the outflow of U.S. jobs to emerging economies may cause U.S. unemployment to rise, income disparity to widen and give rise to new poverty. It is conceivable that deflation could start in the United States if the income it gained from its global advantages dissipated. This could trigger a downward spiral in which U.S. wages fall as unemployment rises, resulting in declining prices. My examination of the U.S. economy following the financial crisis reveals that there is only a very small chance of this deflation scenario occurring. U.S. companies now have an unprecedented amount of capacity to grow. Since there is still enormous pressure holding down consumption, there will be an explosion in jobs and consumption sooner or later. I believe that growth in hiring and spending will be backed by the U.S. government’s determination to do everything possible to create jobs, a characteristic that sets the United States apart from other countries. We must remember that the global economy faces the risk of a shortage of demand because the financial crisis pushed the world to the brink of a depression. Thanks to economic globalization and the information technology revolution, the world is now in a period of unprecedented growth in productivity (which rapidly increases the ability to supply goods). Creating demand is thus vital to stabilizing the global economy. This is why spending is a virtue and saving is not. In particular, industrialized nations must not look back on their excessive consumption as a mistake. Instead, these countries must encourage people to buy goods and services in order to raise living standards. Contents (1) The unique causes of Japan’s deflation and why there will be no U.S. deflation (2) Unprecedented room for growth at U.S. companies – On the verge of a rebound in jobs and consumption (3) Creating demand is the global economy’s most urgent issue – Spending is a virtue, not saving

(1) The unique causes of Japan’s deflation and why there will be no U.S. deflation

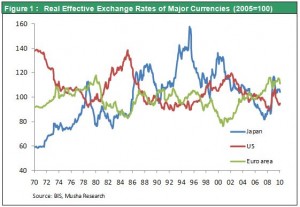

A drop in wages caused by an excessively strong currency will not happen in the United States

Deflation in Japan was caused by factors that were unique to this country. First, an upswing in the yen’s value that went way too far caused Japan’s wages to become much higher than in other countries. Corrective forces pushed down wages, creating steady deflationary forces. But these forces never appeared in the United States and there is no reason they should emerge in the future. As the holder of the world’s key currency, the United States is able to manipulate the dollar’s value as it wishes. This ability also makes it possible to trigger an excessive appreciation of the dollar. For instance, starting in 1995, the United States under the leadership of Secretary of the Treasury Robert Rubin are thought to have adopted a policy of artificially strengthening the dollar. There is no doubt that the high volume of capital inflows along with a strong dollar was what made strong consumer spending and large overseas investments possible. But is it really true that the dollar’s value was raised artificially? Artificial implies that the dollar was pushed up to a point beyond its purchasing power (differential in inflation rates). To see that this did not happen, we need only note that there has been no big change in U.S. prices compared to those of other countries’ (Figure 1). Even if we believe that the dollar’s value was boosted artificially, then the Balassa-Samuelson hypothesis tells us that we should start to see downward pressure on U.S. wages that become higher than in other countries as the dollar strengthens. But this did not happen at all.

The historic causes of Japan’s deflation

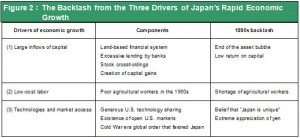

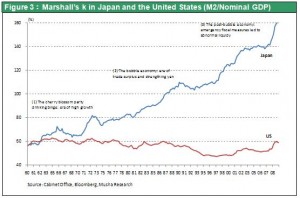

One source of Japan’s deflation was high wages caused by an extremely overvalued yen. But I think one more historic factor deserves to be mentioned. Changes occurred in all three elements that supported Japan’s period of rapid economic growth: (1) large input of capital, (2) low-cost labor and (3) outstanding technologies and easy access to global markets. In 1990, Japanese companies had such an enormous competitive edge that they had become threats to other countries. However, no one noticed that Japan was losing the three elements of its competitive edge at that time.  The three factors that fueled Japan’s era of rapid economic growth were capital input, cheap labor, and technology and market access. When Japan’s economy was expanding rapidly, all three factors were favorable for Japan to the point of being abnormal. Regarding capital input, there was a constant increase in the money supply as a percentage of Japan’s GDP (Marshallian k). With a financial system based on land, Japan’s economy had a built-in ability to make an almost unlimited amount of investments. These investments fueled economic growth through the 1980s. Then the asset bubble burst in 1990. No longer could investors receive a suitable return on the massive amount of invested capital. The result was declines in the productivity of capital and interest rates. Consequently, Japan learned that excessive accumulation of capital produce enormous limitations rather than benefits.

The three factors that fueled Japan’s era of rapid economic growth were capital input, cheap labor, and technology and market access. When Japan’s economy was expanding rapidly, all three factors were favorable for Japan to the point of being abnormal. Regarding capital input, there was a constant increase in the money supply as a percentage of Japan’s GDP (Marshallian k). With a financial system based on land, Japan’s economy had a built-in ability to make an almost unlimited amount of investments. These investments fueled economic growth through the 1980s. Then the asset bubble burst in 1990. No longer could investors receive a suitable return on the massive amount of invested capital. The result was declines in the productivity of capital and interest rates. Consequently, Japan learned that excessive accumulation of capital produce enormous limitations rather than benefits.  Regarding cheap labor, Japan’s rapid economic growth was backed by a supply of low-cost workers coming from farms. This is precisely what is happening in China right now. Between the end of the war and the 1970s, there was an increase in the population of Japan’s agricultural areas. A large number of these people served as a source of cheap factory labor for many years.

Regarding cheap labor, Japan’s rapid economic growth was backed by a supply of low-cost workers coming from farms. This is precisely what is happening in China right now. Between the end of the war and the 1970s, there was an increase in the population of Japan’s agricultural areas. A large number of these people served as a source of cheap factory labor for many years.

The Backlash from the Three Drivers

Finally, let’s look at technology and market access. Many people are convinced that Japan enjoyed a free ride for a long time in the postwar years. In the Cold War era, Japan had somewhat privileged access to U.S. technologies and markets. Because of this privilege, Japan caught up with other countries at low cost. I think that this was a free ride. Everything started to change in the late 1980s, though. Japan was instead subject to unusually unfavorable market terms, as is exemplified by the “Japan is unique” belief and the extreme appreciation of the yen. Following the bursting of Japan’s asset bubble, all three factors that had fueled Japan’s rapid growth became negative factors. The stagnation of the Japanese economy after the end of the bubble was merely the final chapter of the same characteristics that drove growth in the past. In a sense, this was unavoidable. After losing these three advantages, Japanese companies were forced to hold down labor costs even more in order to remain competitive. This explains why falling wages were a distant cause of the start of deflation.

(2) Unprecedented growth potential at U.S. companies – On the verge of a rebound in jobs and consumption

For the reasons that I have just explained, starting in the 1990s, rising labor productivity in Japan failed to improve the country’s standard of living. Any improvement was blocked by the yen’s excessive strength and changes in the three historic factors that fueled Japan’s economic growth in the past. All of these forces are unique to Japan. Therefore, the probability of the United States experiencing Japanese-style deflation is very small.

The reactionary views of anti-globalists

But even if this view is correct, anti-globalists could adopt the stance that there is still no guarantee that the United States will never see deflation created as rising labor productivity causes companies to lay off workers, resulting in an excess supply of labor that pushes down wages and triggers deflation. I cannot deny the possibility that the U.S. could lose the benefits of rising labor productivity to other countries, resulting in falling domestic employment and wages. Anti-globalization forces believe that unemployment will rise, income disparity will widen and give rise to new poverty in the United States as emerging economies take away U.S. jobs. This stance rejects the very causes of improvements in productivity. In this respect, people who embrace this view are adopting a reactionary stance that is equivalent to the Luddite movement (early 19th century) that urged the destruction of machinery because machines take away jobs.

J.A. Hobson’s idea

This stance shares similarities to the observations of J.A. Hobson about the British economy around 1900. He believed that mis-distribution of income in Britain in favor of entrepreneurs and financiers left too little for consumption and created excessive capital surplus. This capital gave Britain the opportunity to overextend itself with imperialistic expansion and invasions. But if this surplus is given to workers in the form of higher wages or to the country in the form of taxes, it would be spent rather than saved. As a result, it would help increase consumption rather than become a cause of overseas expansion. (J.A. Hobson, A study of Imperialism, Iwanami Bunko). Hobson was proposing a Keynesian solution. This is precisely the point where the U.S. economy stands today concerning the benefits of rising productivity backed by globalization. Will these benefits cause U.S. unemployment to rise and consumption to fall (the anti-globalization stance)? Or will globalization create more U.S. jobs and consumption (the stance of optimists and Hobson’s idea).

The unprecedented untapped strength of U.S. companies

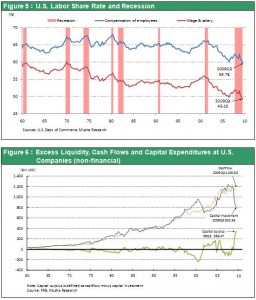

So which of the two scenarios is likely to come true? To determine the answer, let’s take a look at the U.S. economy in the wake of the financial crisis. Based on the following analysis, I believe that scenario 2 is more likely to become a reality. I believe the most significant characteristic of the U.S. economy today is the unprecedented degree of untapped strength in the corporate sector. This strength is evident in the all-time low for labor’s share of income (Figure 5) and the all-time high for idle funds on companies’ balance sheets (Figure 6). The United States moved faster to cut jobs than any other country. Because of this speed, workforce reductions are mostly over. In 2009, the U.S. GDP contracted by 2.4%. Even though this was the smallest decline among major countries, the U.S. unemployment rate posted the largest increase. This figure surged by four percentage points from 5.3% to 9.3% between the second quarters of 2008 and 2009. Only the United States cut employment by more than production among the world’s major countries. This explains why U.S. productivity improved even during a recession. Cutting employment reduced labor’s share of income in the United States to an all-time low in the third quarter of 2009. Normally, labor’s share rises significantly during a recession because the workforce utilization rate falls. But this time, the United States experienced no such increase. Instead, U.S. companies succeeded in holding down expenses to a remarkable degree. U.S. companies also made great progress in reducing the amount of equipment and in improving cash flows. Capital expenditures plunged as factory utilization rates dropped sharply. Of course, this held down the economic growth rate. Capital expenditures fell to a record low of 9.4% of GDP. Despite this drop, corporate cash flows remained generally flat even amid a deep recession. Moreover, free cash flows (an indicator of the amount of excess liquidity) posted the largest-ever increase. These accomplishments show that U.S. companies were able to protect their earnings by reacting rapidly to the economic downturn. This is a defining characteristic of the current recession and one that is inconsistent with newspaper headlines proclaiming the deepest recession of the postwar era.

How are U.S. companies using all their liquidity?

U.S. companies have no problems with bloated workforces or high cost structures. This is why these companies have so much cash on their balance sheets. With all this money to spend, once their confidence in the economy returns, corporate executives are in an excellent position to jump-start the economy by recruiting workers and making positive investments (capital expenditures, acquisitions, stock repurchases, dividend increases). Companies have finished adapting to the downturn and have greatly lowered their break-even points. Furthermore, U.S. manufacturers are seeing a strong rebound in new orders. All these developments point to a big increase in corporate production and earnings in 2010. This gives investors good reason to expect positive surprises from U.S. companies when they announce earnings. At the same time, the unprecedented liquidity on corporate balance sheets will flow to stock markets in the form of acquisitions, stock repurchases and higher dividends. The bottom line is that we now have an excellent environment for a rally in stock prices from the standpoint of both earnings and supply and demand.

U.S. employment and consumption are both likely to climb

Moreover, consumer spending, which is the key component of the U.S. economy, has undergone a correction that definitely went too far. Automobile sales have dropped by half from the peak. Demand for single-family homes is only one-fourth of the peak. We have clearly reached the bottom. In addition, the household saving rate, which is reversely proportional to consumer sentiment, appears to have reached its peak in May 2009. This figure rose from 1.2% in 2008 1Q to 3.7% in 1Q 2009 and then climbed to 4.9% in April and 6.4% in May. The saving rate then declined to 4.9% in June, 4.3% in July, 3.4% in August, 4.2% in September, and 4.1% in October and November. The rate was 4.2% in December and 3.3% in January 2010. A steady improvement in consumer sentiment is almost certain for two reasons. First, job cuts are largely over. The peak was in January 2009 when 740,000 jobs were lost. In December 2009, there was a decline of only 20,000. Second, stock prices are increasing and housing prices have stopped falling. That means consumers are benefiting from the wealth effect as the value of their holdings climbs. By comparison, net assets of U.S. households peaked at $66 trillion in 2007 2Q and then fell all the way to $48.5 trillion in 2009 1Q. By the third quarter of 2009, net assets had rebounded to $53.4 trillion, an increase of $5 trillion in only six months. About another $2 trillion was probably added in the fourth quarter. The impact of this ¥7 trillion increase in U.S. household net assets in the nine months between the second and fourth quarters of 2009 was about half of GDP and can hardly be ignored. As I have just explained, U.S. companies have achieved remarkable improvements in earnings and liquidity while consumption has been under severe pressure. I believe this makes upturns in employment, wages and financial income inevitable, all of which will contribute to higher household income. Creating jobs in order to boost household income is the highest priority of the U.S. government. Elections always focus on this issue. We can even say that doing everything possible to create jobs is the defining characteristic of U.S. politics. If necessary, I think the government is prepared to take follow-up actions to put more people back to work. For these reasons, I have reached the conclusion that deflation will not occur in the United States.

(3) Creating demand is the global economy’s most urgent issue – Spending is a virtue, not saving

The benefits of globalization

Why have U.S. companies performed so well? The reasons are obvious: Companies are benefiting from globalization and the revolution in information technology. However, these two factors are creating a new potential problem for the global economy.

The risk of insufficient demand

The global recession sparked by the financial crisis has created the risk of insufficient demand in the global economy. Globalization and the information technology revolution have produced an age of unprecedented growth in productivity (rapid increase in the ability to supply goods). Agricultural workers in China, India and other emerging countries have migrated to factory jobs. The result is a breathtaking revolution in productivity. But this revolution differs from what happened during the industrial revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries in a critical way: speed. During the industrial revolution, steam engines were the most advanced technology available for workers to use. But today, companies give their employees much more sophisticated equipment (driven by electricity, semiconductors, etc) that raises productivity hundreds of times. Emerging countries with a combined population measured in billions are using this technology to raise productivity rapidly. At this stage, the question is whether or not enough new demand can be created to offset growth in the capacity to supply goods. Depending on the answer, there are two quite different outlooks for the world. If enough demand can be created, the world will see a remarkable improvement in the standard of living in many countries. If enough demand cannot be created, there will be a destructive recession caused by too much production capacity.

How much can we increase consumption in industrialized countries?

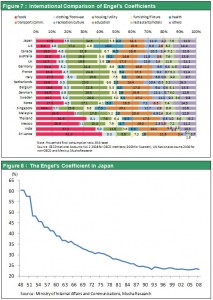

The first place to look for new demand is growth in the internal demand of emerging countries. But productivity in these countries has been increasing too fast for internal demand alone to cover the higher supply. Creating new demand in industrialized countries too is thus imperative. Furthermore, rising productivity in emerging countries is made possible in part by the provision of technologies, capital and markets by industrialized countries. As a result, the industrialized countries as well have a right to create new demand in order to improve their own standards of living. In the early stage of globalization between 2004 and 2007, the United States alone had to bear the responsibility of creating new demand. Fulfilling this responsibility produced excessive consumption and an asset bubble. But both of these excesses were needed. In fact, I think the worldwide recession of 2008 and 2009 happened because this U.S. new-demand-creation mechanism broke down. If this is true, there is no reason for the United States and other industrialized countries to feel any remorse about their excessive consumption. In fact, these countries must aggressively urge their citizens to spend their money in order to improve standards of living. But can industrialized countries realistically hope for an even higher standard of living? My answer is yes. After all, the Engel’s coefficients of these countries are still far from zero. This coefficient divides the expenditures (work) of people into two categories: expenditures needed to put food on the table and expenditures used for higher purposes. In prehistoric days, people had an Engel’s coefficient of 100%. In emerging countries, the coefficient is between 30% and 50%. In industrialized countries, the coefficient is between 10% and 20% (see Figure 7). The conclusion is clear. Even industrialized countries still have more potential to improve standards of living. As explained above, it is highly unlikely that the U. S. and the world will slip back into a recession this year and next. Nevertheless, we cannot overlook the fact that the world economy is constantly exposed to the risk of "excessive supply capacity." My conclusion: What must be done to avoid global deflation Four measures are needed to prevent the outbreak of deflation on a global scale. First is creating advanced consumer-based societies in countries with emerging economies. Second is creating new demand in industrialized countries, which will lead to an even higher standard of living. Third is “depreciating the earth” which means shifting from industries that consume the earth resources to ones that can revitalize the earth (the modern equivalent of building pyramids). Fourth is enacting the required Keynesian initiatives as emergency measures. (See the July 2008 Key Strategy Issue No. 276 titled “Japan must create a means of valuing the Earth” for more information about the theme of depreciating the earth.)