A historic drop in long-term interest rates is an indicator of demand concerns

The steep downturn in interest rates during the past month clearly demonstrates the fundamental error of people who use the “sovereign debt crisis” as an explanation for the current situation. S&P downgraded U.S. debt. Nevertheless, U.S. long-term interest rates, which are the borrowing cost for the U.S. government, have declined to the lowest point since the 1950s. U.K. long-term interest rates have not been this low since the 1890s. In other words, U.K. interest rates are at the lowest level in more than a century. In Germany, long-term interest rates have dropped much faster than in other EU countries. Last week, German interest rates reached a new all-time low by falling below the September 2010 record. As everyone is well aware, interest rates are unusually low in Japan, too. Financial markets are screaming for help because of insufficient demand in all developed countries and the mistaken government policies that are causing this problem.

Today, the U.S., Japan, Germany and U.K. are all struggling with a severe demand gap (insufficient demand). In the private sector, insufficient demand has created a massive volume of excess savings. The most pressing problem right now is to find a way to use these excess savings effectively to create demand and improve living standards. Pessimists often adopt the fatalistic stance that “we should endure insufficient demand because there was too much consumption and too much debt in the past.” But this view is useless for finding a solution to the demand problem. However, during the past month, politicians, financial authorities, rating agencies and others have shifted their focus to cutting debt and preventing undue exposure to risk by financial institutions. As a result, financial markets have been subjected to a constant flow of considerable static. The current situation differs from the subprime loan crisis of 2008. This time, a negative cycle of fear in financial markets has triggered a plunge in stock prices even though no new problem has emerged with regard to the real economy. Many events are causing this turmoil: record-low long-term interest rates; record-high strength of the yen; a record-high gold price; a growing credit risk premium; a rapid increase in the euro LIBOR-OIS spread (risk premium for euro interbank transactions); and rumors that European financial institutions will no longer be able to function. These events are fueling fears about a return to a global economic downturn unless something is done to prevent the European financial crisis from growing into a global crisis.

In addition, the deluge of speculative positions to avoid risk is not centered only on U.S., German, Japanese and U.K. government bonds. Currency speculation is also growing as investors move funds to gold and the yen, the Swiss franc and other currencies. No demand is being created by these movements of capital. This is nothing more than a flow of funds to instruments where there is no demand for capital. These fund movements are extremely harmful to the economy. Action must be taken before this disease destroys the economy.

Growth policies are needed to eliminate the huge supply-demand gap

There are three causes of the enormous supply-demand gap that currently exists in developed countries: (1) a big increase worldwide in the ability to supply goods and services because of the productivity revolution backed by economic globalization and the Internet; (2) the demand side is shrinking because of negative sentiment since the collapse of Lehman Brothers; and (3) the lack of progress with financial and policy initiatives is blocking the creation of new demand. At this time, both government and financial actions are required to generate demand. Only economic growth can solve the debt problem. Furthermore, the conditions needed for growth are in place because productivity is increasing.

In Europe, Germany must decide how to use its large amount of excess savings. Should these funds be channeled to domestic consumption? Or should Germany support emerging EU countries by extending loans and other financial assistance? There is no indication yet of what Germany will do. In the worse case, the financial collapse of small European countries will cause European financial institutions to become insolvent, resulting in a financial crisis in Europe. If this happens, the German economy would probably drop sharply because of excess supply and massive problem loans at financial institutions. There is only one way to avoid this crisis. European fiscal unification is required so that Germany can officially extend fiscal assistance to countries in southern Europe. But time will be needed to achieve a consensus in Germany to take this step. Apparently, we are witnessing a game of chicken with financial markets.

The United States requires (1) Fed chairman Ben Bernanke to take the lead in sustaining the animal spirits that are just now reappearing so that funds are used for longer-term expenditures (for durable goods and up-front investments by companies); (2) an extension of fiscal support to underpin the foundation of demand; and (3) deregulation, tighter regulations and other measures to encourage investments in clean energy, infrastructure and other sectors to create new demand. Japan as well must take actions that can stimulate growth. Aggressive financial initiatives and measures to end deflation are needed in order to increase domestic demand by boosting wages.

However, there is increasing reticence about risk exposure, growth in the risk premium, another drop in prices of mortgage-backed bonds and other problems for a number of reasons. Among them are:

(1) Emergence of a scenario in which Germany and France are lukewarm in their support of the euro, resulting in financial collapse of smaller European countries, a crisis at major European banks and eventually financial panic

(2) Tighter financial regulations (Basel III, Dodd-Frank Act) leading to risk avoidance and serious problems at European banks

(3) Memories of the nightmare of 1937 when U.S. spending cuts ended an economic recovery brought back by the U.S. debt ceiling problem and S&P rating cut

(4) Universal agreement among economists about the need to improve government fiscal soundness

This is not 2008 again.

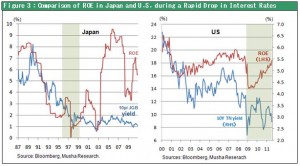

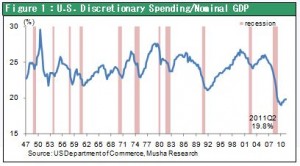

Mounting pessimism is caused by nothing more than the belief that governments have been putting off a final resolution to the 2008 crisis. Pessimists confidently state that current events have revealed this fact. There is no doubt that this view is partially true. But the differences between the real economy in 2008 and now are more important. When the financial crisis started in 2008, there were many excesses in the real economy: consumption, debt and asset prices (a bubble). A recession was unavoidable as the means of compressing demand to trim away these excesses. Today the situation is precisely the opposite. As Figure 1 shows, the ratio of U.S. discretionary spending (spending that is not needed or not urgent: durable goods, housing and capital expenditures) to GDP is at the lowest point in the post-war era. Consequently, even if a double-dip recession starts in the United States, there is very little room for a further decline in real demand since it has already shrunk to an unprecedented level. In fact, there is probably a very high probability that the recession will end with a powerful recovery.

The situation is different from Japan, too.

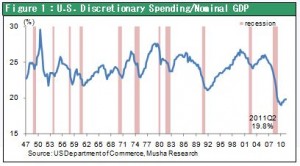

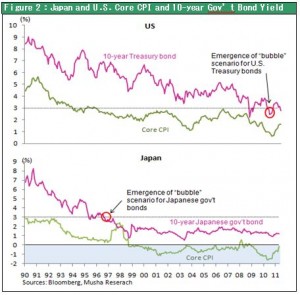

A comparison with Japan (Figure 2) shows that people are very likely to be mistaken to believe that the United States and Europe will go down the same path as Japan: the end of an asset bubble leading to excess debt and finally deflation. If this happens, U.S. long-term interest rates would fall even more. That means investors should sell stocks and buy Treasury bonds. But this is an extremely illogical view. The private sector has an enormous volume of financial assets with returns that are far higher than Treasury bonds. Locking in a return of 2% or thereabouts for 10 years with these bonds is obviously not a reasonable course of action.

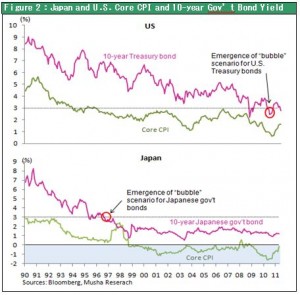

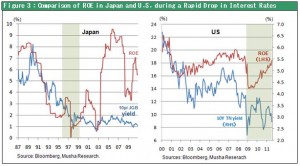

In 1996, the yield on Japanese government bonds was below 3% and deflation was about to begin. The key difference between Japan then and the United States today is a rising stock market backed by strong earnings at U.S. companies. In 1996, Japanese companies were falling behind with restructuring measures to deal with steadily rising fixed expenses and other issues. Along with the consistently strong yen, the result was a downturn in earnings. Moreover, Japan still had not yet determined the actual amount of non-performing loans. U.S. companies, on the other hand, quickly completed restructuring programs and raised labor productivity. Taking these actions produced a sharp rebound in earnings that has reached the previous all-time high. In addition, U.S. financial institutions have completed measures to deal with non-performing loans. In 1996, long-term interest rates in Japan reflected the deflationary economy and declining returns on capital. Today, the situation in the United States is the opposite as interest rates fall as the return on capital improves. Therefore, unlike Japan in 1996, the United States is in a position for an upturn in stock prices based on sound economic principles. Figure 3 shows the significant difference in the relationship between corporate profitability (ROE) and interest rates Japan and the United States when there was a danger of deflation beginning. In the United States, household debt servicing cost coverage (interest expenses divided by disposable income) has dropped sharply and the affordability of housing has climbed to an unprecedented level. Consumer and housing loans are still declining. But the start of an upturn in business loans and other positive signs show that a steady recovery is taking place at financial institutions, too.

Global economic growth will probably continue

In the United States, the debt ceiling has already been raised and President Obama is considering additional economic stimulus measures. With further monetary easing possible as well, it will be difficult for the current one-way negative cycle of pessimism to continue. If the United States can shield itself from the negative effects of the game of chicken between European politicians and the financial markets, prospects will be good for the U.S. economy to continue to stage a steady recovery.

Japan should create a sovereign wealth fund.

In Japan, deepening deflation caused by the yen’s unprecedented strength is creating a crisis. At this point, Japan should do as much as possible to contribute to global economic growth. Enacting extensive growth-oriented measures will stop deflation in Japan. To bring down the yen’s value, Japan should create a sovereign wealth fund for reinvesting the country’s foreign currency reserves overseas.(to is not required) As one of the world’s largest sources of capital, Japan should adopt a stance of risk-taking to support global economic growth. The country should clearly indicate that it intends to channel certain portion of its foreign currency reserves into foreign high-risk, high-return assets rather than U.S. Treasury bonds. Making these investments would contribute to global economic growth and heighten Japan’s stature in overseas financial markets as other investors are running away from risk. Furthermore, Japan should reinforce this stance of utilizing assets to capitalize on benefits of the yen’s strength. If Japan does this, other countries will most likely realize that making the yen too strong is not in their best interests in an international foreign exchange market in which each country is seeking the greatest possible benefits for itself.

In 1996, the yield on Japanese government bonds was below 3% and deflation was about to begin. The key difference between Japan then and the United States today is a rising stock market backed by strong earnings at U.S. companies. In 1996, Japanese companies were falling behind with restructuring measures to deal with steadily rising fixed expenses and other issues. Along with the consistently strong yen, the result was a downturn in earnings. Moreover, Japan still had not yet determined the actual amount of non-performing loans. U.S. companies, on the other hand, quickly completed restructuring programs and raised labor productivity. Taking these actions produced a sharp rebound in earnings that has reached the previous all-time high. In addition, U.S. financial institutions have completed measures to deal with non-performing loans. In 1996, long-term interest rates in Japan reflected the deflationary economy and declining returns on capital. Today, the situation in the United States is the opposite as interest rates fall as the return on capital improves. Therefore, unlike Japan in 1996, the United States is in a position for an upturn in stock prices based on sound economic principles. Figure 3 shows the significant difference in the relationship between corporate profitability (ROE) and interest rates Japan and the United States when there was a danger of deflation beginning. In the United States, household debt servicing cost coverage (interest expenses divided by disposable income) has dropped sharply and the affordability of housing has climbed to an unprecedented level. Consumer and housing loans are still declining. But the start of an upturn in business loans and other positive signs show that a steady recovery is taking place at financial institutions, too.

In 1996, the yield on Japanese government bonds was below 3% and deflation was about to begin. The key difference between Japan then and the United States today is a rising stock market backed by strong earnings at U.S. companies. In 1996, Japanese companies were falling behind with restructuring measures to deal with steadily rising fixed expenses and other issues. Along with the consistently strong yen, the result was a downturn in earnings. Moreover, Japan still had not yet determined the actual amount of non-performing loans. U.S. companies, on the other hand, quickly completed restructuring programs and raised labor productivity. Taking these actions produced a sharp rebound in earnings that has reached the previous all-time high. In addition, U.S. financial institutions have completed measures to deal with non-performing loans. In 1996, long-term interest rates in Japan reflected the deflationary economy and declining returns on capital. Today, the situation in the United States is the opposite as interest rates fall as the return on capital improves. Therefore, unlike Japan in 1996, the United States is in a position for an upturn in stock prices based on sound economic principles. Figure 3 shows the significant difference in the relationship between corporate profitability (ROE) and interest rates Japan and the United States when there was a danger of deflation beginning. In the United States, household debt servicing cost coverage (interest expenses divided by disposable income) has dropped sharply and the affordability of housing has climbed to an unprecedented level. Consumer and housing loans are still declining. But the start of an upturn in business loans and other positive signs show that a steady recovery is taking place at financial institutions, too.