謹賀新年 2013年 From 武者リサーチ

2013年はいよいよ日本復活の年になるだろう。安倍政権の誕生は、世評のように民主党の失政による消極的選択と、シニカルに評価するべきではない。2010年代以降の日本の進路選択にかかわる変化ととらえるべきである。尖閣事件は1850年代の黒船来航に匹敵する意味を持つ。どちらも一事によって、日本の進路選択と国民世論の糾合を果たし、事後のトレンドを決定づけるものと言える。

黒船来航は日本と西洋との技術、経済力の圧倒的格差を見せつけ、植民地的隷属か経済発展による自立かの二者択一を明白にし、国民世論を開国と富国強兵、臥薪嘗胆に導いた。同様に尖閣問題は、対中連携(従属)か日米同盟かの二者択一を国民に迫った。共産党独裁体制の中国に従属する選択肢は民主主義と資本主義が高度に発展した日本にはなく、日本は必然的に日米同盟を基軸に、国家意識の高揚と国防の充実、経済発展を図る以外にない。1955年体制以来続いた「反共か容共か」、「親米か反米か」の神学論争は尖閣の一事によって決着がつき、以後論争の焦点は、日米連携のもとでいかに中国を封じ込めるかの戦術論議に移っている。そうした戦略課題に対して解を持っているか否かが、今回総選挙において大きく政党間の浮沈を分けた。

この変化は政治、地政学にとどまらない。むしろ日本経済と市場に深遠なる変化を与えるものと予想される。対中宥和色、反ビジネス色、反成長色の民主党政権から日米同盟基軸、プロビジネス、成長路線の安倍自民党政権への転換は、真に55年戦後体制を終わらせ、22年間の円高デフレ株安時代を終わらせる画期ともなるだろう。リーマン・ショック以降日本に定着した「反成長主義」悲観論を一掃させるものとなるだろう。

(1) 地政学が近代日本の興亡を規定した

明治維新体制と日米同盟が日本の盛衰を支配した

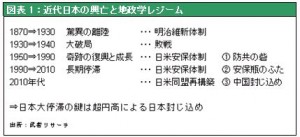

経済は一定の期間は、経済の論理によって変動し成長する。しかしより長期の歴史を考えると、経済の興隆と衰退を決定してきたのはひとえに政治であり、ことに安全保障を柱とする国家戦略であった。このことは明治以降の日本の歴史を振り返ると、一目瞭然である。1867年から1930年代末までの60年間近代日本が世界史にも稀な驚くべき躍進を遂げたのは、言うまでもなく明治維新による近代国家の樹立があったからである。1930年代後半から1940年代の経済大破局は、言うまでもなく第二次世界大戦により、近代日本が負けたからである。そして1950年から1990年までの40年間、再度日本は奇跡の復興と大成長を遂げた。戦後日本の経済躍進を支えたのは日米安保体制であった。1950年の朝鮮戦争によって日本経済は経済拡大の好循環が与えられ、それはバブルが弾けるまで続いた。

図表1:近代日本の興亡と地政学レジーム

(2) 1990年の地政学環境変化=日米安保の変質と日本経済の挫折

1990年に起きた日本の突然の麻痺

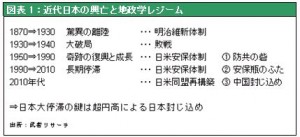

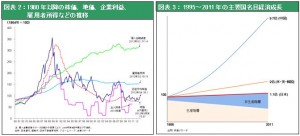

さて1990年以降日本経済は歴史上にも稀な長期の停滞に陥った。この停滞は、戦後成熟した先進国が経験したものの中でも、際立っていた(図表2)。長期デフレに陥り名目経済はほぼ20年間完全なゼロ成長であった(図表3)。戦後の日本経済は1990年までの一本調子での著しい高成長と1990年以降の成長を停止した20年に二分されるが、これほどのコントラストは、どのような経済論理を駆使してみても、分析困難なものである。

図表2: 1980年以降の株価、地価、企業利益、雇用者所得などの推移

図表3: 1995~2011年の主要国名目経済成長

1990年日米安保体制の変質

なぜ1990年に近代日本の4度目の転機が訪れたのかを理解するには、やはり政治の大きな枠組みが変化したという地政学的観点の導入が不可欠である。1990年に起こったことは、日米安全保障条約の変質である。1990年までの日米安保はまさに極東の防共の砦としての役割があった。日本はアジア前線における不沈空母として、政治・軍事・経済の全てにおいて米国の世界戦略の要にあり、その様に育てられた。従って1990年のソ連・共産主義世界体制の崩壊により日米同盟の役割は、一旦は終わった。それにもかかわらず日米同盟が存続し続けたが、その戦略的意義は大きく変質したと考えられる。1990年初頭、米国では安保瓶のふた論が語られていた。なぜ米国は巨額のコストを払って日本に駐留するのかという問いに対してその意義は日本封じ込めにある、と説いたのである。世界第二位の経済強国となった日本が、再度軍国化し対外膨張を始めないとも限らない。日本の核武装、軍事大国化を抑制することがアメリカの軍事戦略上緊要だ、というのである。もちろん1989年の天安門事件で刃を見せた共産党独裁国家中国の存在もあり極東の不安が消えたわけではなかったが、当時の中国は米国の世界戦略にとっては取るに足らない相手であった。

米国の最大の脅威となった日本の産業競争力⇒日本封じ込めへ

このように存続するにはしたものの、日米安保の意義は政治・軍事面では大いに希薄化した。しかし、経済となると話は全く変わってくる。1980年代後半から日本経済脅威論がまきおこった。放置すれば日本経済が米国経済・産業を衰退させるという危機感が米国を捉えた。実際、民生用電気機械、半導体、コンピュータ、自動車などの基幹産業において、米国企業は日本企業に負け続け、雇用にも深刻な影響が表れていた。金融力を飛躍的に高めた日本企業による米国の買いあさりも起きた。そこで日本の経済躍進を食い止め米国の経済優位を維持するというのは、米国の世界戦略にとっても最重要課題の一つとなった。その論理は、日本経済は官僚支配・規制・系列・土地本位制金融などの資本主義とは異質の要素により競争力を強めておりそれは不公正である、日本の異質な部分を変えさせ日本企業を米国企業とおなじ土俵で戦わせることが必要(レベリング・プレイングフィールド)という「日本異質論」である。そして実際日本に膨大な圧力がかけられ、1980年代後半以降日本の経済政策は米国対応に翻弄され続けた。そして米国の要求を大いに受け入れた。日米安保瓶のふた論は米国の対日経済戦略の遂行に当たって、大きな力となったのである。実際日本には市場経済とは相いれない前近代的経済慣行が多く残っており、それがかえって日本企業の対外競争力を高めていた。従って分析論としては「日本異質論」は正当な側面が大きかったが、それを活用した対日圧力は覇権国家米国の経済利害の貫徹そのものであった。

(3) 日本封じ込め体制は超円高により日本にデフレをもたらした

超円高が日本封じ込めの切り札となった

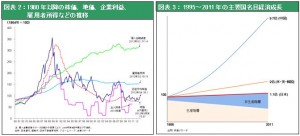

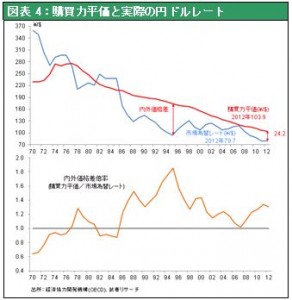

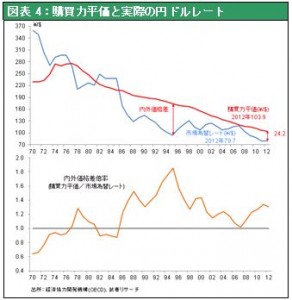

1990年以降20年間の「日本病」と形容される経済停滞はこの米国の経済圧力によってもたらされた、と言える。日本を経済的に封じ込めるプロセスにおいて、決定的だったのは、異常な円高であった。大幅黒字国の日本の通貨が強くなるのは、変動相場制のもとでは当然である。しかし日本の円高の場合、通貨の購買力から見て異常であった。普通は各国通貨の変動は購買力平価(購買力で計測した通貨の実力)に比べてプラス・マイナス30%が限度なのに、日本円の場合には一時2倍という異常な過大評価が与えられた(図表5参照)。それにより日本企業のコストは一気に国際水準に比べて2倍となり、日本の労働者の賃金も国際水準からみて2倍となったために、企業は雇用削減、正規から臨時への雇用シフト、海外移転などを実施した。この結果企業にとっての単位生産物あたりの労働コストは大きく低下し、なんとか競争力を維持できた。しかし日本の労働賃金はその犠牲となり、長期にわたって緩やかに低下し続け日本にデフレをもたらしたのである。

図表4は円ドルレートと購買力平価(円の実力)の推移だが、1970年代初頭の購買力平価220円の時、実際の円ドルレートは360円であった。日本企業は220円のコストで作ったものを輸出し360円稼げたわけである。それが1990年代に入ると200円の購買力平価に対して円ドルレートは100円以上の円高となった。日本企業が200円のコストで製造したものを輸出しても100円しか稼げなくなり著しい逆ザヤとなったのである。超円高が変わらない以上日本企業はコストを劇的に抑制し、購買力平価を200円から100円に引き上げる以外生き延びる道はなかった。そして日本企業は見事にそれを実現したが、それは労働賃金の引き下げ、雇用環境の悪化と日本のデフレという大きな副作用を残したのである。

図表4:購買力平価と実際の円ドルレート

この円高が単なる経済的現象でないのは、円高で強くなった日本の金融力に大きな足かせがはめられていたことを見ても明らかである。19世紀イギリスの繁栄のピーク、ビクトリア時代には、イギリスは強大なポンド高を通じて世界の貴重な経済資源を買いあさり英国人の商機を広げた。本来なら日本の場合も大幅な黒字を使って、世界経済に対する支配力を強めることができたはずである。しかし実際には米国の企業や不動産などの貴重資源を買うことができず、もっぱら金利の低い米国短期国債の購入を続けざるを得なかった。不完全な円高であった。

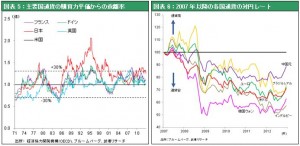

2008年の世界金融危機以降、グローバルデフレシナリオに基づく投機対象として円が著しく過大に評価されたが(図表6)、それも異常な円高の継続により、人々の投資行動に強い円高バイアスがビルトインされてきたためとも考えられる。

図表5:主要国通貨の購買力平価からの乖離率

図表6:2007年以降の各国通貨の対円レート

(4) 2010年に訪れた地政学新時代

共産党専制国家中国の台頭

さて2010年に入り、再び日米安保条約を再評価する必要性が高まっている。1990年代の「日本異質論」に代わっての「中国異質論」の台頭である。中国は1980年代末の日本以上に、近い将来近隣破壊的強さを持つことを恐れられている。現在中国のGDP(2011年、7.3兆米ドル)はほぼ米国の2分の1であるが、名目成長率を米国5%、中国15%、仮に人民元が2割切上げられるとすれば、ほぼ5年あまりで名目GDP規模は米国に肉薄することになる。外貨準備はさらに増大し中国のバイングパワーが他を圧することは間違いない。中国のそうしたプレゼンスは現在の問題ある市場主義、民主主義、法治主義、財産権、知的所有権の状況からすると、世界のかく乱要因になりかねず、覇権国米国が容認できるものではない。しかも中国の強さは、日本以上に技術・資本・市場などを海外に依存した成長構造に起因しており、それはフリーランチの側面が大きい。

対中圧力に日米同盟は緊要

中国を抑制し自己変革の圧力をかけ続けるためには、その隣国の日本のプレゼンスの高まりがバランス上求められることである。長期経済停滞により日本人が資本主義や市場経済に対する信頼を失い、漂流し始めれば、東アジアは大きく不安定化する。ここは日本経済の浮上が、覇権国米国にとっても緊要となってくる場面である。アーミテージ元米国国務副長官やジョセフ・ナイ ハーバード大教授などの米戦略論のオピニオンリーダーは、日本のプレゼンスの低下、二級国への陥落を真剣に危惧している。それはペナルティーとしての異常な円高が再現する可能性を一段と低くするものである。図表7に見るように、1980年代半ばから2000年前後まで、世界の貿易黒字を一手に集め、強大な競争力を誇ってきた日本のプレゼンスは大きく低下している。2012年日本は原発稼働停止による化石燃料の輸入増もあり6兆円強の大幅貿易赤字に転落する見通しである。所得収支の黒字経常収支では黒字が維持されているものの、世界の経常黒字順位では日本は中国、ドイツ、主要石油輸出国に追随する立場となっている。日本封じ込めを目的とした1990年以降の安保瓶のふた論の時代は終わりつつあると言える。それは超円高を転換させる最も大きな力となる。

図表7:各国の経常収支対世界GDP比

(5) 安倍リフレ政策の意義

そうした場面で登場した安倍政権のリフレ政策の意義は大きい。米国では2008年のリーマン・ショックは、信用は修復され経済活動もショック前に戻り、危機の後遺症は着実に癒されている。バーナンキFRB議長に主導された創造的金融緩和策が、米国を危機から救ったと言えるだろう。しかし米国をはじめ主要国の着実な回復に対して日本の劣後が顕著である。日本株の独り負け、円独歩高、世界唯一のデフレが続く。リーマン・ショック後底値から直近株価の回復度合いは米国2倍の上昇に対して、日本は1割と危機の震源地である米欧をはるかに上回る低迷ぶりである。また円は主要国通貨に対して極端な上昇となった。2007年初比で韓国ウォンは対円で5割、米ドル、ユーロは3割の減価となり、日本製造業の競争力を著しく傷つけている。その要因は円の独歩高に投影される日銀の消極的緩和姿勢にあると思われるが、それがいよいよ大転換する場面である。

超円高、デフレをもたらした根本要因、①米国の地政学的要請、②日銀の円高デフレ容認姿勢が転換すると投資におけるあらゆるセットアップが変化する。2013年以降、Cash is king 心理の根本的廃棄、リスク選好がトレンドとなるだろう。

図表8:2007年以降の主要国中央銀行総資産

図表9:主要国株価推移(2009年3月=100)

この円高が単なる経済的現象でないのは、円高で強くなった日本の金融力に大きな足かせがはめられていたことを見ても明らかである。19世紀イギリスの繁栄のピーク、ビクトリア時代には、イギリスは強大なポンド高を通じて世界の貴重な経済資源を買いあさり英国人の商機を広げた。本来なら日本の場合も大幅な黒字を使って、世界経済に対する支配力を強めることができたはずである。しかし実際には米国の企業や不動産などの貴重資源を買うことができず、もっぱら金利の低い米国短期国債の購入を続けざるを得なかった。不完全な円高であった。

2008年の世界金融危機以降、グローバルデフレシナリオに基づく投機対象として円が著しく過大に評価されたが(図表6)、それも異常な円高の継続により、人々の投資行動に強い円高バイアスがビルトインされてきたためとも考えられる。

図表5:主要国通貨の購買力平価からの乖離率

図表6:2007年以降の各国通貨の対円レート

この円高が単なる経済的現象でないのは、円高で強くなった日本の金融力に大きな足かせがはめられていたことを見ても明らかである。19世紀イギリスの繁栄のピーク、ビクトリア時代には、イギリスは強大なポンド高を通じて世界の貴重な経済資源を買いあさり英国人の商機を広げた。本来なら日本の場合も大幅な黒字を使って、世界経済に対する支配力を強めることができたはずである。しかし実際には米国の企業や不動産などの貴重資源を買うことができず、もっぱら金利の低い米国短期国債の購入を続けざるを得なかった。不完全な円高であった。

2008年の世界金融危機以降、グローバルデフレシナリオに基づく投機対象として円が著しく過大に評価されたが(図表6)、それも異常な円高の継続により、人々の投資行動に強い円高バイアスがビルトインされてきたためとも考えられる。

図表5:主要国通貨の購買力平価からの乖離率

図表6:2007年以降の各国通貨の対円レート