Mar 18, 2016

Key Strategy Issues Vol.K299

Central banks respond with negative interest rates to the challenges posed by today’s excess profit

(1) Japan is first in the world to enact negative interest rates; China crisis headed for a resolution

Brilliant initiatives of the BOJ’s Kuroda will reverse the global stock market downturn

As stock prices plunged worldwide in January and February, the joint measures taken by central banks to deal with a crisis advanced to a new stage. There are also expectations for faster economic growth in industrialized countries as the benefits of cheaper oil begin to emerge in March and April. If the crisis in China can be contained as well, stock markets around the world may stage a rebound.

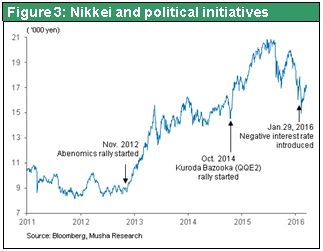

The initiatives of Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda stand out among the global crisis management activities. Mr. Kuroda has destroyed the belief that the Bank of Japan is ineffective by taking the highly unusual step of enacting negative interest rates. He has also positioned Japan at the forefront of global monetary easing. This move by the Bank of Japan is the first full-scale action by an industrialized country central bank in response to speculators’ attempts starting in the second half of 2015 to create a market sell-off. Deflation remains the greatest risk for the global economy because of slowing economic growth in China. Preventing deflation is therefore the most important duty of industrialized country central banks.

Japan is the obvious choice to lead this deflation fight. No other country suffered more from deflation or has more experience with the war against deflation. Even so, we should greatly admire the boldness of Mr. Kuroda’s actions. He believes that deflation is the root of all evils, that deflation should be eradicated at all costs and is taking reasonable steps to accomplish this goal. This boldness is a characteristic necessary for a wartime commander. After all, we are not in a period of normalcy because a war against deflation is under way.

Following the moves of the Bank of Japan, the European Central Bank enacted additional monetary easing in March. This step is viewed as all-out war. In the United States as well, despite showing confidence in the US economy, the Fed is slowing the pace of interest rate hikes due to the risk of global financial instability.

The increasing likelihood of the containment of Chinese Crisis

Prospects are improving for a resolution to the crisis in China for the time being. The turning point was the G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors Meeting that took place in Shanghai on February 26 and 27. The communique of this meeting included the statement that recent market volatility does not reflect underlying fundamentals of the global economy and all policy tools must be used to achieve market stability. All major financial authorities of the world thus clearly established a unified stance for fighting rampant selling by speculators.

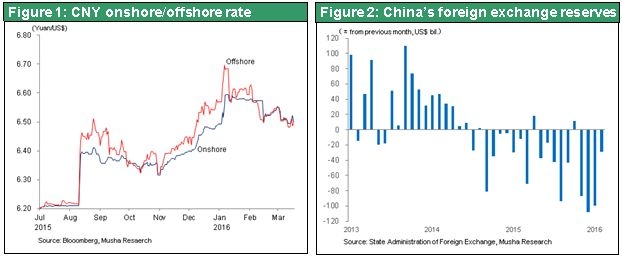

This stance also incorporates a new direction for fiscal policy and other initiatives. In addition, the G20 clearly demonstrated the desire to stabilize currencies and the willingness to tighten measures for monitoring and controlling movements of capital. China’s freedom to take actions, which has been the focus of attention, has increased significantly as a result. The communique states that excess volatility and disorderly movements in exchange rates can have adverse implications for economic and financial stability. This statement implies that China should be allowed to tighten capital controls in order to accomplish the two major objectives of preventing competitive currency devaluations and preserving the yuan’s value. Taking this action will enable China to escape from the international financial trilemma and shut down the pathway for speculative sales of the yuan. George Soros thinks that a hard landing in China is unavoidable and expects a sell-off of the yuan, Hong Kong dollar and other Asian currencies. Therefore, the yuan and matters involving foreign exchange have obviously become the key aspect of the China crisis. However, prospects for this situation to stabilize will probably improve going forward.

After the Shanghai G20 meeting, US Secretary of the Treasury Jacob Lew went to Beijing for a long meeting with Premier Li Keqiang. Mr. Lew said that a devaluation of the yuan should be avoided because it could spark global competitive devaluation. Mr. Lew said that obtaining the agreement of China regarding this point was a big accomplishment of the meeting. Obviously, a decline in the yuan’s value would be detrimental for China, too. This is the most potentially dangerous event of all because a weaker yuan would lead to a vicious cycle driven by currency instability and a financial crisis that produces a deepening economic crisis.

This meeting was very significant because it indicated that the United States and China had established a joint battle line to protect the yuan. The yuan’s exchange rate became much more stable following the meeting. Moreover, China’s foreign exchange reserves fell only $28.5 billion in February, much less than the monthly declines of about $100 billion in prior months. This smaller decline will probably be another source of confidence about China.

China’s crisis will be contained by the September Hangzhou G20 at the latest

The 2016 G20 Summit will take place in Hangzhou on September 3 and 4 with Chinese President Xi Jinping serving as host. This gathering will be a demonstration on a global stage of the prestige of China. Will this event take place amid a financial crisis in China as the yuan falls? Or will the crisis be ending because of forceful actions by the Chinese government? The answer is clear because of the priority the government places on saving face. This is why we can expect China to do whatever is needed to hold the yuan steady. We will have to closely watch the monthly economic data from China. These figures will be indicators of upcoming events, such as if the outflow of capital and drop in foreign exchange reserves can be stopped and if the yuan will fall. Despite this uncertainty, the possibility of an end to China’s crisis within the next six months has increased significantly.

(2) Critics are off target – All critics of quantitative easing oppose negative interest rates

Once China settles down, the benefits of negative interest rates in Japan will probably quickly appear in the form of a stock market rally. Negative interest rates mostly generated criticism. Two newspapers reacted positively. The Yomiuri Shimbun says that negative rates show the Bank of Japan’s resolve concerning additional monetary easing and eradicating deflation. The Financial Times headline reads “Kuroda reasserts deflation fighting stance.” So both papers view this as a war-like measure. But most reactions are negative. Here are some headlines in Japanese newspapers: “Negative interest rates are a last-resort adventure” (Mainichi Shimbun); “Negative interest rates – Don’t forget the limits of relying on the Bank of Japan” (Sankei Shimbun); “Will negative interest rates be an effective policy?” (Asahi Shimbun); and “International dialogue needed for market stability without relying on the Bank of Japan” (Nikkei Shimbun).

The persuasive element of the critics is Japan’s failure to boost stock prices and bring down the yen. Immediately after announcing negative interest rates, stock prices in Japan surged and the yen fell sharply. But both of these movements ended quickly. The next week, stock prices plunged and the yen strengthened. The Nikkei Average retreated to the ¥14,800 level and the yen rose rapidly to the ¥110 to the dollar on February 12. The fall in stock prices was not arrested at their levels prior to the start of negative interest rates. They plunged to the levels seen in October 2014 when phase 2 of QQE was announced.

However, the weakness of stock prices and strength of the yen in the second half of February were caused solely by global events. Stock prices plummeted worldwide regardless of whether or not the Bank of Japan was implementing monetary easing. There was a risk-off environment worldwide. People always buy the yen whenever the market is in a risk-off phase, which makes the yen stronger. Consequently, it is a big mistake to link declining stock prices and a stronger yen with actions by the Bank of Japan.

The decline to negative territory of long-term Japanese government bond yields has fueled criticism of negative interest rates as well. People sold stocks and bought these bonds immediately after the start of negative interest rates. This was precisely the opposite of what the Bank of Japan wanted. This gave critics another reason to believe that negative interest rates are ineffective. But this opposite effect will last only briefly. The possibility of interest rates becoming negative means that there is an unlimited potential upside for government bond prices. In fact, immediately after the start of negative interest rates, short-term speculators bought government bonds to capture capital gains. Due to this buying, yields on long-term government bonds did become negative. In fact, the negative yielding JGB return will definitely become negative if a bond is held to maturity. Thus people may think that a negative interest rate will attract a limited volume of money to government bonds for short term.

(3) Quantitative easing with negative rates will be powerful with very high stock prices

This may be obvious, but negative interest rates may have a surprisingly big impact. The first is to force money out of Bank of Japan demand deposits, which are the ultimate safe asset to more high risk high return assets. Until now, critics of quantitative easing said that it is pointless to increase the money supply as long as there was no desire to borrow money (because of a lack of confidence in the economic outlook). Certainly monetary easing has failed to achieve the ultimate goals. At first, the Bank of Japan hoped that investors and financial institutions would use the money from government bond purchases by the Bank of Japan to buy assets with a higher return and increase loans. Shifting money to assets with risk would increase the volume of investments and prices of various assets, resulting in higher expectations for inflation. But this virtuous cycle of portfolio rebalancing did not occur. The April 2014 consumption tax hike stopped Japan’s economic growth, an economic crisis emerged in China, stock prices fell worldwide, the yen became stronger and other events altered the economic climate. As a result, monetary easing did not prompt investors to rebalance their portfolios. Proceeds from government bond sales were simply left idle in Bank of Japan demand deposits. Now that these deposits bear a negative interest rate, there are hopes that banks will move these idle funds to assets with risk and loans.

The second impact is widening the methods that can be used for expanding monetary easing. The Bank of Japan now holds more than 30% of all Japanese government bonds. Buying more bonds will become increasingly difficult. For assets other than government bonds, like ETFs and REITs, the Bank of Japan’s holdings are extremely large in relation to size of the secondary markets for these assets. However, even negative interest rates have started at 0.1%, there is no ceiling on how much farther the Bank of Japan can go into negative territory. The central bank, which has unlimited amount of ammunition, will only become even more intimidating.

The third surprisingly big impact of negative interest rates results from the change in investors’ ability to earn profits due to the automatic shift in the interest rate structure caused by negative rates. This change may significantly increase the effectiveness of monetary easing. The fourth impact is the possibility of a big improvement in market sentiment regarding risk-taking in response to Mr. Kuroda’s bold actions that show no fear of risking unwanted side effects. As long as the resolve of the Bank of Japan, backed by its unlimited ammunition, remains clear, investors who are shunning risk will have no option other than to reduce their risk-averse positions.

If money flows out of demand deposits because of negative interest rates, the result would be a smaller monetary base. This could lower expectations for inflation. If this happens, the Bank of Japan would have to buy more government bonds. This is why negative interest rates should probably be used only in conjunction with quantitative easing in order to heighten the effectiveness of negative rates.

Negative interest rates, which Japan is trying for the first time, are creating concerns about unwanted side effects. Nevertheless, this is an extremely powerful measure for raising prices of stocks, real estate and other high-risk, high-return assets while bringing down the yen. Higher stock and real estate prices along with a weaker yen due to portfolio rebalancing by institutional investors have always been the primary means of transmitting the benefits of quantitative easing. In comparison, shouldn’t we expect negative interest rates to produce benefits more directly?

(4) Central banks take on the challenge posed by the age of excess profits

The new reality for central banks

The most profound question is why central banks around the world have implemented monetary easing on an unprecedented scale as if they were being pushed by someone to act quickly. The reason is that central banks are facing a reality that is completely different from anything in prior years. Government agencies and other financial authorities were forced to alter their policies because they are responsible for producing results. From the standpoint of conventional wisdom and people who firmly believe in textbooks, the central banks of the United States, Japan and Europe have been implementing forbidden initiatives one after another. But this is actually unavoidable.

This is the new reality: Earnings (profit margins) at companies are climbing at the same time that interest rates are falling. The widening gap between profit margins and interest rates is the primary sign of this new reality. It has been many years since the last time the link between movements of earnings and interest rates disappeared. The mission of monetary policies is to use the proper allocation of capital to achieve the greatest possible economic benefits for the public (growth in jobs with inflation under control). But now profit margins are rising steadily while interest rates fall. In this environment, conventional monetary policies are unable to correct the tendency for capital to flow to risk-free assets. Moreover, this environment makes the deflation risk even worse by increasing surpluses of capital and labor. Central banks have responded to this new reality by taking on the new challenge of enacting policies like zero interest rates, quantitative easing and negative interest rates.

Excess earnings are responsible for this unprecedented reality: r1>g>r2

The financial difficulties that central banks must resolve can be explained by this relationship: r1>g>r2 (r1 is corporate earnings/profit margins, r2 is the cost of capital (interest rate) for companies and g is the rate of economic growth). The existence of two inequilibrium at the same time is a defining characteristic of today’s economic environment. Profit margins are high. Dividend yields are 2%, the earnings yield on stocks is 7% to 8% and ROEs are high at around 8%. On the other hand, companies can borrow funds at a very low cost. Government bond yields are less than 1% in Japan and Europe and less than 2% in the United States, which is far below economic growth rate. The result is an enormous gap between earnings and the cost of capital.

Normally, profit margins and interest rates should move in tandem. In fact, this has usually been the case. Interest rates are higher when the economy is healthy and companies report strong earnings. After all, profits and interest are both returns on capital. Consequently, profit margins and interest rates should be the same. This explains why textbooks tell us that r1 = r2 is what the economy should look like. Today, we are seeing a huge gap between r1 and r2. How should we interpret this situation? This is the key to understanding the current economic environment. Thomas Piketty, author of Capital in the Twenty-first Century, argues that profit margins are higher than economic growth (r>g). Therefore, wealth and income inequality is increasing. But this alone is not enough. There is still one more reality: Interest rates are lower than the rate of economic growth (g>r).

The abnormal reality of r1>g>r2 is most likely caused by the substantial excess earnings at companies resulting from rising productivity associated with today’s industrial revolution. Simply put, companies are making a lot of money. Then, instead of reinvesting these funds, companies are letting the money sit idle and interest rates are falling. The big decline in interest rates in industrialized countries points to the existence of surplus capital. Furthermore, the lack of growth in jobs (consistently high unemployment, low labor force participation rate, slow growth in wages) points to the existence of a labor surplus.

Why have these surpluses increased to the point where they have become problems? The cause is probably the big increases in the productivity of labor and capital at companies. The new industrial revolution is defined by IT, smartphones, cloud computing and many other forms of progress. This revolution and globalization have together produced an unprecedented upturn in productivity. Companies require much less labor and capital as a result. Strong growth in earnings was accompanied by an increase in idle labor and capital.

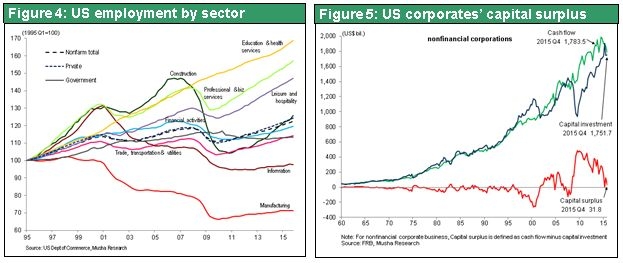

In their book The Second Machine Age, the authors Eric Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee, who are professors at MIT, say that the second industrial revolution has arrived. Two centuries ago, the first industrial revolution used the invention of mechanical power to use machines for replacing manual labor. Economies grew and living standards improved as productivity increased dramatically. The current second industrial revolution is driven by the invention of information and communication equipment and systems. Now these machines are starting to replace intellectual labor. Figure 4 shows US employment in several sectors. As you can see, rising productivity fueled by the new industrial revolution has significantly reduced the number of jobs in the manufacturing and information sectors. Additionally, the cost of machines has dropped sharply because of IT progress and the cost of building factories is much lower because globalization makes it possible to operate factories in emerging countries. All these events mean companies can do business with much smaller investments. In the United States and Japan, it has been a long time since companies didn’t need to reinvest the entire amount of their depreciation. Figure 5 shows the amount of surplus capital (the amount by which cash flows exceed capital expenditures) for companies. Surplus capital has been climbing since 2000 and especially since the global financial crisis started in 2008. Now it is common for prominent companies like Apple and Google to hold massive amounts of idle capital.

High earnings and surplus capital have rapidly reduced the speed of money velocity

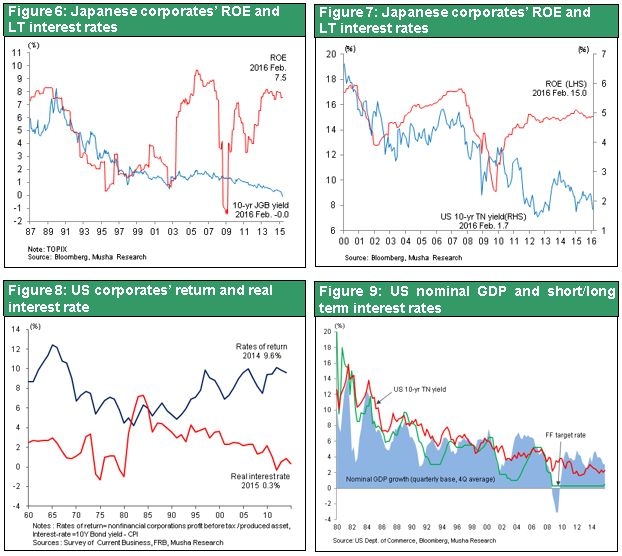

The difference between long-term interest rates and ROEs in Japan and the United States (Figures 6 and 7) clearly demonstrates the existence of both strong earnings and a surplus of capital. Some people regard the declining long-term interest rates in the United States as a sign of a decline in profit margins (the ability of companies to earn profits). But the fact is that a growing volume of idle money generated by strong earnings is the cause of the downturn in long-term interest rates. The gap between profit margins and interest rates widened during the decade that started in 2000. Companies are very profitable, but interest rates are falling because of an excess of capital. This is evident from Figure 8, which shows US companies’ profit margins and interest rates and Figure 9, which shows the US nominal GDP and long and short-term interest rates. In 2005, Alan Greenspan, who was Fed chairman at that time, described as a conundrum the existence of low long-term interest rates despite a robust economy and Fed’s tightening measures. This conundrum did not go away even after the start of the global financial crisis. The same year, Ben Bernanke, who was the next Fed chairman, said that a global saving glut was the cause of the conundrum. But looking back now, we can see that the cause was not a general surplus of savings. It is becoming increasingly clear that the real cause was a surplus of money at companies.

Falling long-term interest rates can be viewed in two ways. One is to believe the cause is the decay of capitalism as the ability of companies to earn profits declines. The other is to believe the cause is rising profitability backed by higher capital productivity. These views lead to opposite opinions about quantitative easing and negative interest rates. The decaying capitalism belief supports the view that quantitative easing is a mistake that will produce a bubble by supplying more paper money in response to a deteriorating economy. The rising profitability belief supports the view that quantitative easing is a sound and proper policy that will put to work the idle capital that currently exists in financial markets.

If idle capital actually exists, then a further reduction in the cost of capital should increase economic benefits for the public by putting that capital to work. Targeting the elimination of surpluses was the reason for the creativity of the monetary initiatives (quantitative easing) started by former Fed chairman Ben Bernanke. But negative interest rates take this creativity to the next level. Surplus labor and surplus capital are essentially two sides of the same coin. Whenever there is an excess of labor, there will also be an excess of capital.

Time for fiscal measures; perhaps a new age of Keynesianism on the horizon

Clearly, there is a need for measures aimed at eliminating surpluses in order to create demand. However, raising the Fed funds rate and thus the cost of capital for companies when there is a surplus of capital (low long-term interest rates) is likely to make the capital surplus even greater. The result will probably be a recession, lower interest rates and a big downturn in stock prices. When Alan Greenspan was Fed chairman, interest rate hikes produced a reverse yield curve (short-term rates higher than long-term rates) in 2000 and 2005-2006. This created two financial crises: the collapse of the IT bubble and the collapse of the housing bubble. Both of these events can be called natural outcomes of inverted yield curve.

Doubts remain about whether or not the Fed’s actions were correct. At that time, the economy did not need monetary tightening in order to burst an asset bubble. Measures were required to guide capital to sectors with sustainable demand rather than to bubble-creating investments. Broad-based macroeconomic initiatives were required. The economy needed government spending, tax reforms and various institutional changes while continuing to enact monetary easing. So the question was if the government would enact policies that facilitate or block the effective use of surplus capital. Promoting the use of capital would push stock prices higher. Blocking the use of capital would cause stocks to fall. Consequently, the stock market has become highly dependent on government policies. Both quantitative easing and negative interest rates are reasonable policies for achieving the goal of converting idle capital into useful demand.

Lawrence Summers, Paul Krugman and many other US opinion leaders believe that initiatives are needed to increase demand creation and economic growth. They want to see more fiscal initiatives, tax reforms, income redistribution and other actions while maintaining an easy-money environment. Too much of a burden is placed on monetary policy as the means of recycling idle savings into the real economy. This is why there may be a need for Keynesian policies. In other words, there may be a need to use the public sector for absorbing surplus capital and low interest rates in order to contribute to demand creation.

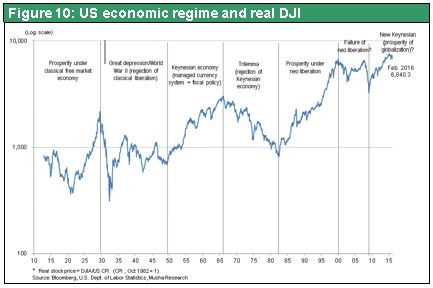

Figure 10 shows real US stock price index along with changes in the economic regime. During the past century, there have been long-term ups and down in real stock prices. Each one can be linked to the success or failure of an economic regime. Rising stock prices up to 1929 were the result of the success of classical liberalism. The subsequent downturn between 1930 and the early 1940s was caused by the collapse of classical liberalism. Stock prices rose in the 1950s and 1960s because of the success of Keynesianism. Then the collapse of Keynesianism brought down stock prices in the 1970s. Next, the new liberalism supported a stock market rally between about 1980 and 2000. The collapse of new liberalism then brought stock prices down between 2000 and 2009. Today, we may be on the verge of a phase in which new Keynesianism drives economic growth.