Apr 22, 2014

Strategy Bulletin Vol.119

Why Japanese Stocks Will Rebound (2)

The economy is absorbing the consumption tax hike; all indications point to an end to deflation

Stocks in Japan are down 14% in 2014, the worst performance in the world by far. Falling stock prices appear to be an indication of mounting worries about the outlook for Abenomics and the possible end of the effectiveness of the Bank of Japan’s quantitative easing. But investors are overlooking the multitude of positive signs in economic fundamentals. I believe we are very likely to see a dramatic shift in market sentiment due to improving fundamentals and the resolute actions of the Japanese government and Bank of Japan. Japan may be on the verge of an “Abenomics reality” rally that is just as powerful as the “Abenomics expectation” rally that occurred between November 2012 and May 2013.

Signs of the end of deflation are finally becoming stronger, in contrast to the expectations of pessimists. Moreover, investors should not underestimate the steadfast determination of Prime Minister Abe and Bank of Japan Governor Kuroda. In the unlikely event that any uncertainty about ending deflation surfaces, Japan will undoubtedly take decisive actions that give the public an irrefutable reason to expect inflation. These initiatives will ignore criticism involving the moral hazard, policy taboos and stopgap measures. Altering the mindset of the Japanese public is what matters most. The people of Japan want to restore a powerful economy in response to the growing geopolitical risk created by China’s increasing strength. This sentiment is implicitly underpinning Japan’s steadfast economic initiatives.

(1) A steady stream of evidence that deflation is ending

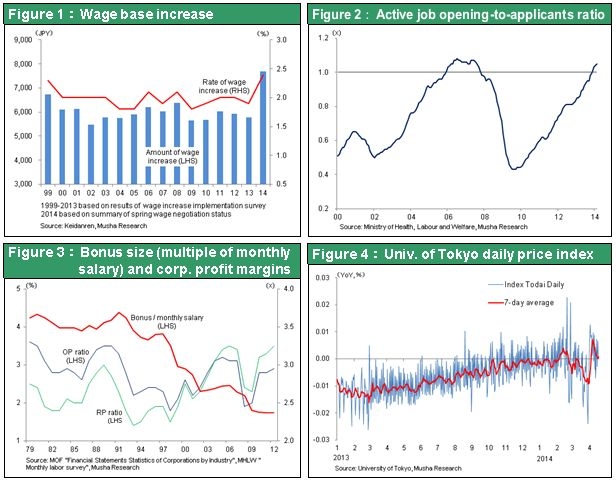

Wages are rising and have reached the highest level in 16 years

Let’s examine the numerous signs that deflation has come to an end. First, wages are rising at a rate of 2.4% (at companies listed on the TSE first section), which is more than \7,000 and the highest level in 16 years. After adding the increase in summer bonuses, total annual growth in wages in Japan may be more than the 2% negative impact of the consumption tax hike. The labor market is improving, too. For example, the active job opening-to-applicants ratio is more than one for the first time in six years. Japan can also expect a benefit from the end of government worker salary cuts, which lowered national government salaries by an average of 7.8% in fiscal 2012 and 2013. Ending this reduction will raise salaries by \300 billion for national government workers alone.

The higher consumption tax increases price-setting flexibility

Companies are passing on the higher consumption tax to consumers. According to the Tokyo University Daily Price Index, prices are up 0.4% after taxes during the first three weeks of April. This shows that a broad adjustment in prices is taking place in addition to passing on the consumption tax hike. Upward price rigidity has been viewed as a cause of deflation. But now we are witnessing the start of a major shift in the tendency for companies to hold down prices as they watch the moves of competitors. This demonstrates the belief of retail and restaurant company executives that their mission is to prevent a return to deflation. Price revisions that took place on April 1 may have been a great opportunity for companies to regain their ability to change prices that had been frozen because of expectations for deflation to continue. The rush to buy prior to the consumption tax hike was smaller than when the tax rose in 1997. The subsequent drop in demand was smaller, too. As a result, it is increasingly likely that the negative impact of the consumption tax hike will be almost negligible.

No more predictions for a stronger yen

The overvalued yen was regarded as the most significant cause of deflation. But the yen is now much weaker and there are no signs of another upturn in the yen’s value. Exchange rates are determined mainly by three factors: (1) the speed at which central banks print money (the Bank of Japan is the fastest); (2) the trade surplus or deficit (Japan has an unprecedented deficit); and (3) real long-term interest rates (with effectively negative rates, Japan has the lowest rates in the world). For the first time, all three of these factors are pointing to a weaker yen. For many years, Japan’s wages were extremely high compared with wages in other countries because of the yen’s strength. This created prolonged downward pressure on wages. The strong yen immediately reduced earnings of manufacturers, which limited their ability to pay their employees. Even companies with solid earnings had to hold down wages and retain earnings because of expectations that the yen’s future strength would cause earnings to fall. Furthermore, deflation originating with the yen’s strength began to affect the service sector associated with domestic demand. The result was downward pressure on earnings and wages in the service sector. But now a dramatic change is taking place in this negative cycle as fears of another upturn in the yen dissipate and expectations for the yen to become even weaker take hold.

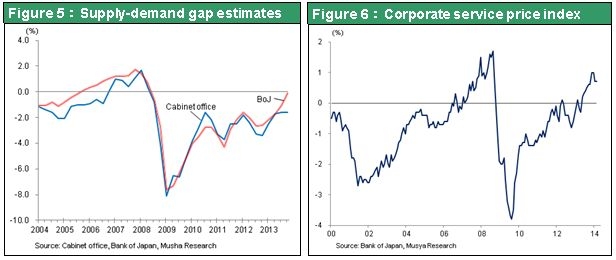

The supply-demand gap is rapidly narrowing

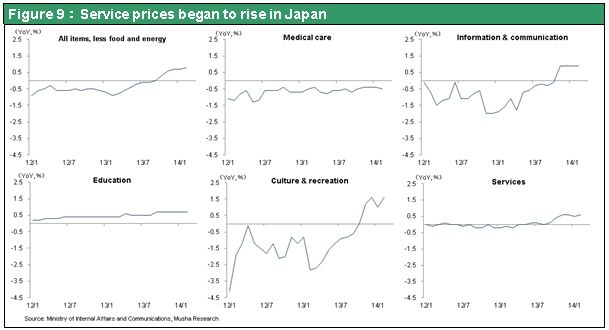

The supply-demand gap, which greatly influences inflation and wages, is rapidly becoming smaller. According to Japan’s Cabinet Office, this gap was 8.1% at the economy’s deepest point following the Lehman shock and grew to 3.7% immediately after the earthquake and tsunami of 2011. The latest report shows that the gap has declined to only 1.6% and the Bank of Japan estimates that the gap is currently about 0%. Supply is particularly tight in the construction industry, which has slashed supply in recent years. The result is a big increase in unit prices for construction. The limited supply of labor has spread to the restaurant and other sectors, resulting in higher hourly wages for part-time workers. Due to these events, the cost of services for companies was up 0.5% from one year earlier in February, the biggest upturn since 1993. Higher prices for communication, education, entertainment, lodging, construction and other services were behind this increase.

(2) Why Japan’s deflation was unique; wages and service prices are turning around

Deflation obviously inflicted severe damaged on Japan’s economy. But two sectors suffered the most. Deflation consistently limited demand by significantly cutting the allocation of income to workers and income and asset allocation in the service sector. Ending deflation will resolve this distortion and lead to expectations for a big increase in demand.

The stage is set for higher wages

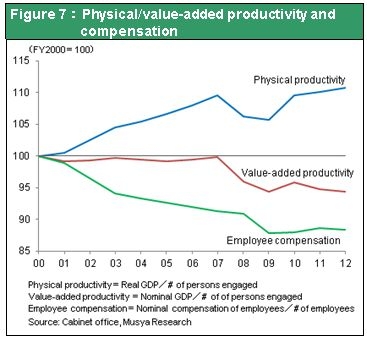

Figure 7 shows physical productivity (real GDP per employed worker), added value productivity (nominal GDP per capita) and nominal wages per capita (worker remuneration) since 2000. Productivity has increased as prices fell. Nevertheless, you can see that nominal economic scale declined and the amount that workers received from the shrinking pie decreased even faster. Consequently, there was an unjust loss of household consumption power because workers did not receive any benefits from higher productivity.

The unjust theft of workers’ consumption power

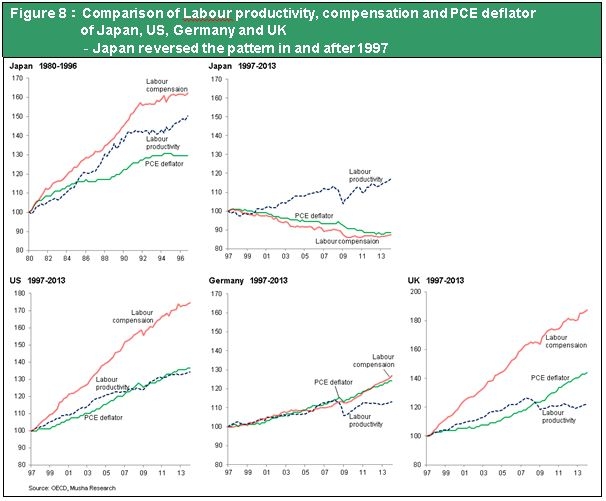

Figure 8 shows how Japan’s wages, prices and productivity have changed over the years and how Japan compares with other countries. The abnormal situation in Japan since deflation started in 1997 is obvious. Prior to 1997, wages rose faster than prices (which means higher living standards) and faster than productivity (which increased the unit cost of labor). After 1997, this situation reversed in Japan. Workers’ productivity continued to climb but prices declined and wages fell even more. Two activities of companies are the probable causes. First, companies cut wages because of the increasing need to lower costs in response to falling prices. In other words, companies responded to falling selling prices by lowering their unit labor cost. Falling prices were triggered by a strong yen and asset deflation. For example, the yen’s extreme strength brought down prices of exported goods and real estate prices in Japan were declining. The result was a negative cycle of deflation and wage cuts.

Fearful companies made retaining earnings their first priority

The second cause is that Japanese companies consistently reduced the portion of income that was allocated to workers while increasing the amount retained. As earnings recovered, companies ended up with massive surpluses of capital (large free cash flows and cash holdings). Japan’s corporate sector had an enormous volume of savings. Two factors are probably responsible. One was the need for a cushion against expected future losses due to pessimistic outlooks including the expectation for the yen to remain strong and continuation of the global financial crisis. The other factor was the absence of any need to raise wages because deflation reduced workers’ cost of living.

Outflows of capital from companies will accelerate

These factors that were pushing down wages are now very different. At the very least, the Bank of Japan’s quantitative easing has succeeded at eliminating any outlook for a renewed upturn of the yen or downturn in real estate prices. Furthermore, there is no need for companies to keep a cushion of savings now that the global economy is recovering and the United States and Europe have come back from the financial crisis. That means the pieces are in place for companies to release their accumulated savings in the form of dividends, stock repurchases and wage increases. Companies are well positioned to respond aggressively to Prime Minister Abe’s call for higher wages. In addition, forecasts for Japanese to continue reporting record-setting earnings indicate that the conditions for wage hikes will remain in place. Figure 3 shows that the correlation between the size of bonuses and corporate profit margins ended around 2000. Since then, bonuses have remained low even though profit margins rebounded. With profit margins consistently high once again, we can expect to see an increase in bonus payments.

Service deflation hurt Japan’s service sector

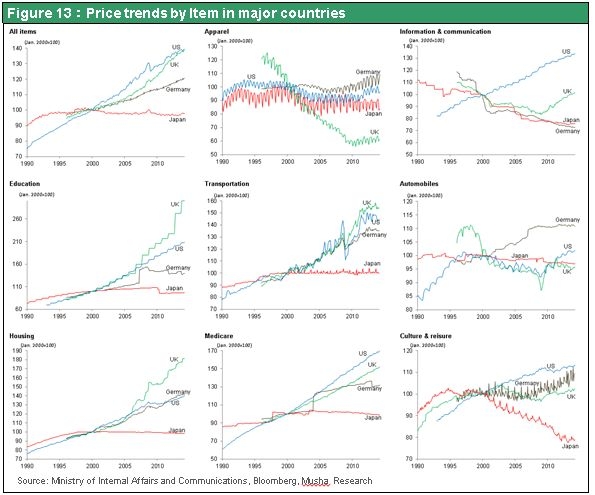

Japan’s service sector was a victim of deflation along with workers. Figure 13 shows how prices in different categories changed in major countries. As you can see, Japan’s deflation occurred in the domestic demand service sector. Prices of products like apparel, electronics and automobiles that are manufactured in emerging countries declined worldwide. Furthermore, fees for communication and other technology-linked services fell worldwide along with technological advances. But Japan alone in the world experienced a downturn in all categories of services.

Falling prices of services undermined earnings in the service sector for the following reasons. There is a large gap between productivity growth in the service and manufacturing sectors. Despite this difference, companies in the service sector had to match the wage increases of manufacturers. To maintain their earnings, service companies were therefore forced to raise prices. Low growth in productivity does not equate to low importance in society. In fact, demand for services increased in Japan in tandem with living standards. Growing demand for services made Japan’s service sector the country’s largest source of job creation. All industrialized countries of the world rely entirely on the service sector for job creation. To recruit the required number of workers, service companies had to charge higher prices so that they could boost wages to match salaries in the manufacturing sector. In other words, service companies were forced to raise prices of services to match the difference in the rate of productivity gains between the manufacturing and service sectors. Falling prices of services in Japan brought down earnings in the service sector and thus wages. As a result, job creation in Japan’s service sector fell far behind job growth in the US and European service sectors.

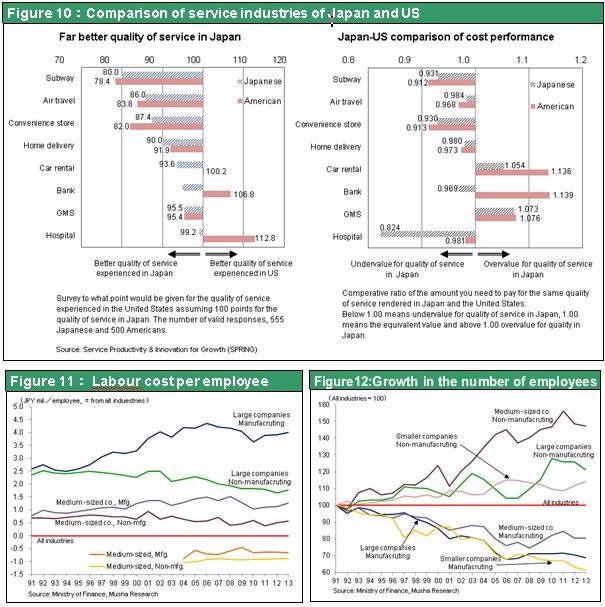

Ending deflation will stop low prices from keeping service productivity low

Many people believe that productivity is low in Japan’s service sector. Falling prices and underpriced services are probably responsible for this perception. As you can see in Figure 10, Japan ranks among the world leaders in the quality of services. But prices do not reflect this quality and the amount of added value is small. Productivity is low as a result. Statistics for companies in Figures 11 and 12 show that deflation has hurt the service sector even more than manufacturers. In the manufacturing sector, wages have declined only slightly as companies cut their workforces. However, there is a widening wage gap between services and manufacturing because wages fell sharply at service companies as they hired more workers. In addition, manufacturers have been expanding production and sales operations overseas while cutting their workforces in Japan. Taking these actions shielded manufacturers from much of the negative effects of deflation. On the other hand, service companies were unable to avoid the impact of falling selling prices by using overseas production, mechanization and other measures to cut costs. This is why deflation caused wages and profit margins to fall in the service sector.

Figure 10 shows that cost-performance in Japan’s service sector is much higher than in the US service sector. This research was conducted in Dec, 2008 when $1=90Yen. Therefore under the current exchange rate, Japanese service sector cost performance may be 10% better than this research would seem to indicate. This difference demonstrates that there is significant potential for raising prices of services in Japan. The difference is also a sign of the potential for increasing service exports like tourism.

These points lead to the following two conclusions. First, the end of deflation in Japan signifies that prices of services will rise. Second, rising prices of services will produce substantial growth in employment and earnings in the service sector. Furthermore, signs of this growth are already appearing.

(3) Change is possible in reasons for pessimism

There are two legitimate concerns about the economic outlook in Japan following the April consumption tax hike. First is the possibility of a drop in consumption power as the higher consumption tax and inflation erode real wages. There is no doubt that real income in Japan fell briefly immediately after the tax increase. However, as I noted earlier, Japanese companies have retained earnings rather than pay out as wages the substantial benefits they reaped from rising productivity. Accumulating earnings gave companies protection against unforeseen risks. But prospects for the occurrence of such problems are now much lower than before. Consequently, companies have ample funds for increasing bonuses, giving workers more overtime, shifting jobs to full-time employees and other actions. Taking these steps will probably enable cash wages to climb faster than inflation.

The second concern is based on the belief that the yen’s decline is having a negative impact because the weaker yen is not producing benefits in the form of higher export volume. The weaker yen would definitely be a drag on the Japanese economy if prices of imports increase but export volume does not. However, as I explained earlier, there is a close relationship between expectations for deflation backed by a strong yen and falling asset prices caused by risk avoidance (a higher risk premium). Expectations have now shifted from deflation to inflation because the yen has clearly changed direction. The benefits of this shift in expectations will probably be much greater than the benefits of the weaker yen itself.

Ultimately, portfolio composition will change

Changes in fundamentals that I have described in this bulletin have been largely overlooked by the large number of economists and investors who have been accustomed for many years to expect deflation. They believe that ending deflation is almost impossible. This is why people who embrace this sentiment refuse to buy stocks and still keep most of their money in Japanese government bonds and cash, which have almost no return. However, changes in fundamentals should be regarded as proof that people afflicted with the endless deflation expectation syndrome will soon be forced to make a big shift in their thinking.