Jul 02, 2014

Strategy Bulletin Vol.122

The contradiction between the end of deflation and portfolios predicated on more deflation

Japanese investors are about to miss the boat

Japanese stocks may end the deadlock in the world’s financial markets

A feeling of deadlock is spreading in the world’s financial markets. Volatility of financial assets of all prices is declining. Furthermore, there is a moderate upturn in the prices of stocks, bonds, emerging currency currencies and gold. Economies in the United States, Europe and Japan are growing steadily while risk involving emerging countries shrinks. At the same time, the world’s major central banks are all implementing easy-money policies. The result is a reappearance of the Goldilocks market (a balanced risk-taking environment that was not too hot or cold) that occurred from around 2005 until the collapse of Lehman Brothers. What will break up this deadlock? A powerful stock market rally in Japan may be the answer.

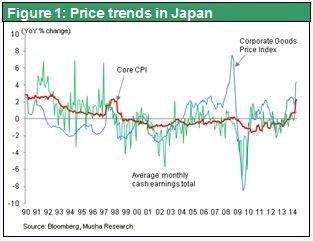

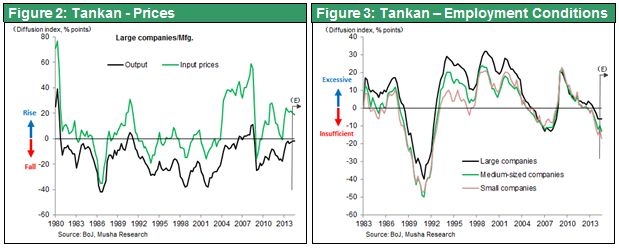

Deflation has ended; Japan’s employment and price indexes are improving

The June Bank of Japan Tankan that was released June 1 had good news. The brief economic downturn after the April 2014 consumption tax hike was negligible. Furthermore, a quick recovery is anticipated. There was also a big upward revision in capital expenditures, which are vital to economic growth. Regarding prices, there is an improvement in selling prices amid expectations for less upward pressure on purchasing prices. There are signs of an improvement in the employment picture, too. Japan is seeing an increasing shortage of workers at companies of all sizes, from large corporations to small and midsize companies. Labor shortages last occurred in Japan between 1988 and 1990 and 2006 and 2007. In addition, the outlook is for a consistent improvement in inventories and other elements of supply and demand. All these factors mean that Japan will undoubtedly experience a further increase in upward pressure on prices.

Although the Bank of Japan may not achieve its inflation goal of 2% in 2015, the bank has succeeded in largely eliminating the possibility of a return of deflation. I stated that the 2% inflation target will be difficult to reach because upward pressure on prices in Japan would weaken following the end of the yen’s decline last year. However, there is no likelihood of the return of deflation. In the unlikely event that inflation shows signs of weakening, the Bank of Japan will definitely take additional steps for monetary easing. Up to 2012, most economists in Japan, including at the Bank of Japan, as well as investors thought that ending deflation would be almost impossible. They believed that quantitative easing alone could not push up prices. But now no one is saying that deflation will continue. Everyone agrees with the view that deflation has been eradicated. However, now pessimists have shifted to another viewpoint. They are worried about stagflation because economic growth will be blocked by the impending elimination of the supply-demand gap and the limit to Japan’s capacity to supply goods. My position is that it is obvious that ending deflation directly equates to raising productivity, which in turn boosts the ability to supply goods. This is why I think stagflation fears are a mistake. However, investors are focused instead on whether Japan will see inflation or deflation.

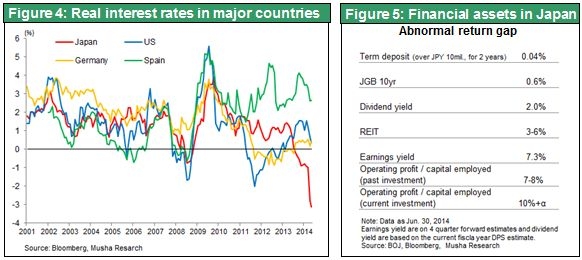

Negative real interest rates make holding cash and Japanese government bonds a risk

The reason for this focus is that an end to deflation will force investors in Japan to make a major shift in their portfolios. As you can see in Figure 4, Japan has the lowest real long-term interest rate in the world. Moreover, this interest rate is negative. If deflation has truly come to an end, the negative real interest rate will definitely continue for a long time. The supply of Japanese government bonds will remain tight because of the massive amount of surplus savings in Japan as well as the Bank of Japan’s bond purchases. U.S. interest rates are staying low, too. In this environment, we can expect the yield of 10-year Japanese government bonds to remain at about 0.6% for the time being. Even if this yield rises, it will stay below 1% and thus stay below inflation. Negative real interest rates mean that more loans translate into more income. Furthermore, interest cannot cover the decline in asset values caused by inflation. As a result, the value of assets is eroded. So-called safe assets like cash and government bonds are the worst possible place to keep money. “Cash is king” with deflation, but now “cash is the worst” instead.

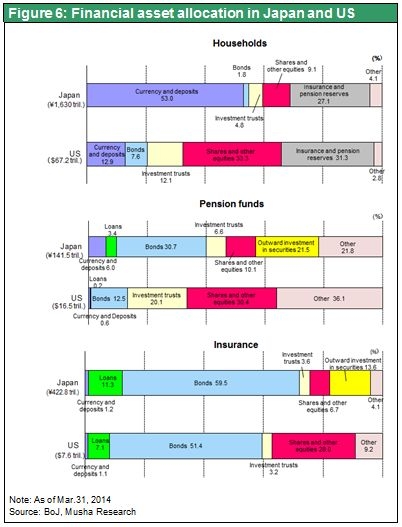

Even though these changes are occurring, there has been no change at all in the portfolios of Japanese investors. Individuals, pension funds, insurance companies and other major categories of investors have been channeling the majority of their capital to cash and Japanese government bonds. In 2013, stocks increased as a share of these portfolios for the first time. However, the only reason was higher stock prices. Last year’s stock market rally in Japan was fueled entirely by foreigners. Japanese investors are still trapped by the unrealistic assumption that deflation will continue. This explains why cash, bank deposits and Japanese government bonds account for a large percentage of portfolios in Japan. But we are at last about to see a change in these portfolios, which are highly unusual compared with investments in the rest of the world. The final countdown to the start of this shift has started. Reforms at the Government Pension Investment Fund to increase holdings of assets with risk will probably significantly alter the widespread assumption in Japan that more deflation is coming.

The movement of assets to investments with risk by Japanese investors will influence the deadlocked dollar-yen market, too. Growing overseas investments by these investors will produce downward pressure on the yen. More pressure comes from Japan’s ¥13 trillion trade deficit and direct investments of about ¥10 trillion by Japanese companies to acquire overseas companies. In addition, if individuals, pension funds and insurance companies in Japan all continue to invest aggressively overseas, the result will be powerful forces for weakening the yen. Furthermore, negative real interest rates encourage investors to short the yen (establish positions where they owe money denominated in yen). There is also a possibility that speculators around the world will turn their attention to the outlook for a weaker yen. If this happens, the yen may begin a major long-term decline. According to OECD purchasing power parity figures for 2013, the U.S. dollar is worth ¥102.6. Since the current exchange rate is about right, any short-term change in this rate will probably be slow.