Jan 20, 2015

Strategy Bulletin Vol.133

There is no Black Swan, equities to rise on boosted global reflationary measures

~ Oil, Russia, Greece, Switzerland - maybe just noise ~

The markets turned risk averse at the beginning of the year, against a background of a rising mood of crisis

The market at the beginning of the year still harbors the same turbulence as was seen last year. The Nikkei stock average suddenly plunging 7% from its December high triggered a wave of uncertainty amongst participants. The plunge in the Russian currency (the ruble), the Greek general election, and its sudden policy shift by the Swiss National Bank (with its decision to abandon the foreign exchange rate cap) - the sudden outbreak of apparently endless discontinuities continuing to hit the markets, and the surge of instability that ensued, resulted in the risk averse mood just getting stronger. However, as mentioned below, these sudden events came out of the blue that they were all developments that had her fundamental basis in economic rationality, and so it's hard to think of that as being black swan events triggering catastrophe.

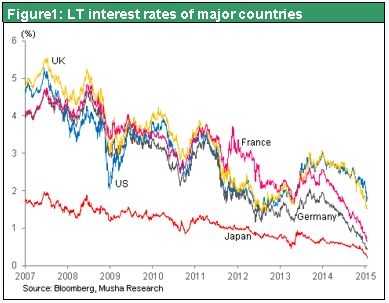

The fundamental cause of the instability is the recurring ghost of deflation, and it is this factor that continues to spook the markets. The high for the oil price last year was $115 a barrel for WTI, but the price subsequently plummeted to just $45 a barrel in the first half of January. The long-term bond yields of the major nations also continued to nosedive at the same time, with Germany and Japan recording their lowest yields in history (Japan: around the 0.1% level; Germany: 0.4%; and the US: 1.7%). If these yields were to be left as they are, they could easily end-up causing a deflationary crisis to materialize. On the other hand the weakness in crude oil and the decline in interest rates both serve to reduce business expenses and living costs, and are therefore positive factors in encouraging growth. The turmoil in the markets can be thought of as demanding an appropriate policy response.

The pessimistic hypothesis that it's once again necessary for us to bear in mind has resurfaced. Its representative is the charismatic Bill Gross who is known as the ‘bond king’, and the foundation for his view remains the same old circular reasoning on credit: pointlessly repeated expansion in credit by the central banks, quantitative easing (QE) now also past its sell-by date, asset prices that have continued to rise relentlessly now set to peak soon - these are the points that he is stressing. But there is little evidential foundation for the credit cycle rolling over. There are no countries betting on the risk of economic recession being forced to tighten the fiscal purse strings. The plunge in the crude oil price, the events in Greece, and the policy shift by the Swiss National Bank - all of these factors are links to renewed growth and avoidance of deflation, and so are connected to the promotion of demand creation policies which means that they surely add up to a reason for strength in equity prices.

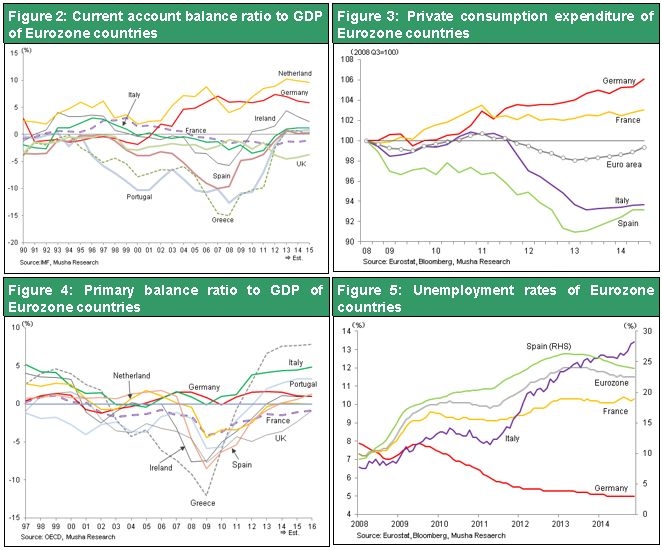

The problem is excessive savings and insufficient demand, and the solution is to bolster reflationary policies

With Greece now firmly in the spotlight, bad memories of the Greek Shock of 2010 are re-emerging and people are clearly bracing themselves for another crisis. But the current situation and the Greek crisis of 2010 are fundamentally different in nature. The problems back then lay in Greece and other southern European nations having excessive levels of consumption and debt. But nowadays the threat of excessive debt emerging in Greece and in the nations of southern Europe has been dispelled by a curtailment of consumption across the region. As you can see from figure 2, the foreign/external current-account deficit (by comparison to GDP) of the nations of southern Europe was formerly around 10%, but is now hovering around zero or perhaps a fraction higher. Moreover, looking at the fiscal balance in terms of the primary financial balance, all of the countries of southern Europe, including Greece, are in the black. This is due to rising interest rates and the elimination of the fiscal deficit in each country, which have in turn resulted in a dramatic lowering of the standard of living for the populations of each nation. The results of the economic slowdown have also caused the unemployment rates of the southern European nations to soar.

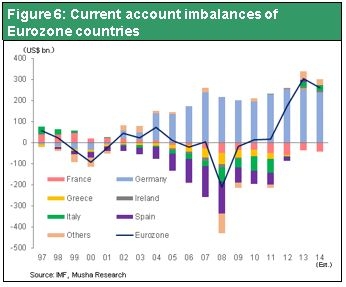

The current problems of the entire Eurozone lie in excessive savings and insufficient demand. As you can see from Figure 6, prior to 2010 the southern European nations had accumulated large deficits, but there was a current account balance held in equilibrium across the euro zone as a whole because of the large surplus that Germany was generating at the time. The current account deficit of the southern European nations was cleared. However, far from declining, the current account surplus recorded by Germany saw an even greater rate of increase which resulted in the euro zone as a whole sinking into a position of huge excessive savings. It was this surplus of savings that triggered the remarkable decline in interest rates.

As a result, an appropriate response in 2010 was the suppression of consumption and the repayment of debt in the southern European nations, but this subsequently resulted in an economic recession occurring thereafter. In response to this, the current problem is the exact opposite of having excessive savings and insufficient demand and, so, the appropriate response in this case is the elimination of excess savings by creating demand; in other words, stimulating growth by introducing reflationary policies. Germany is faced with the problem of accumulating an enormous surplus of savings due to its huge current account surplus, but by adopting a policy of fiscal and monetary tightening it is now heading towards turning its back on reflationary policies. The result of this is that the Eurozone as a whole is facing an increasing risk of falling into the sort of deflationary spiral that Japan fell into. In other words, the major cause of the current instability in the financial markets is the lack of an appropriate response by Europe in confronting the reality of insufficient demand and the key point remains that the European stance as a whole depends upon an improvement driven by a softening in the stance adopted by Germany. Consequently, the snap election in Greece and the loosening of its grip on the fiscal front, with the prospect of further quantitative easing by the ECB currently becoming more clearly apparent, makes it possible to envisage a strong chance of the turmoil in the markets being powerfully quelled.

Global reflationary policies sought in Switzerland too

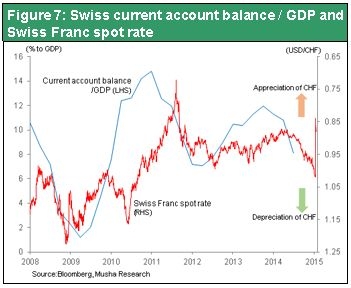

The Swiss franc issue also has the same fundamental nature as this problem. Switzerland has accumulated an enormous current-account surplus because of its extremely strong industrial competitiveness (see Figure 7). In comparison to Japan’s current-account surplus, which even at its peak was 4% against GDP due to the unavoidable huge strengthening the yen experienced in the past, Switzerland's massive surplus is continuing at a rate of 14% and, so, it was natural that its huge currency strength and excessive savings would trigger an interest rate decline. The suppression of the strength of the currency by exchange-rate intervention ran counter to the market logic, so the natural route was for it to become impossible to maintain the currency ceiling. Given that Switzerland's excessive savings had swelled to an unsustainably high rate, the entirely new response by the Swiss National Bank, consisting of the toleration of Swiss franc strength and reinforcement of negative interest rates, both combined to reduce the excess savings which in turn delivered a contributory impact in terms of global reflationary impetus. The ball is in the court of the excess savings nations of Switzerland, Germany, China and other countries with substantial surpluses and they bear the responsibility of driving reflation.

It is absolutely essential to strengthen reflation

Everybody is concerned about the prospect of deflation, and whether or not we fall into deflation depends upon the policy measures adopted. The process of rapidly raising productivity by means of the new industrial revolution is also resulting in clearly rising surpluses of manpower and capital. The growth in China’s economy has been continuing to single-handedly absorb surpluses of manpower and capital to date that's the brakes are being slammed on, but China's foreign trade surplus is also expanding again as imports fall. The disappearance of growth in imports of crude oil by China over the course of the past year has been the biggest factor behind the recent decline in the crude oil price. Consequently, if the economic policies of the major global nations had allowed for some degree of adjustment to deal with this lack of demand, they may have not needed to fear instability at the level currently experienced in the market. The core of this continues to be the quantitative easing undertaken by the United States and, despite successive interest rate hikes over the course of the year, it appears that it has been possible to weather these with a sufficient degree of patience, so there has been no sign of moves to throw cold water over expectations of demand growth in the market. In Japan, too, the inauguration of the third Abe administration has tended to ease any such fears. If the quantitative easing by the ECB triggers the adoption of inflationary policies by the nations of the Eurozone then the situation will sure be even more greatly improved.

The concern of the markets is for a recovery in economic conditions, and the decline in the crude oil price will be viewed as a positive factor in this regard

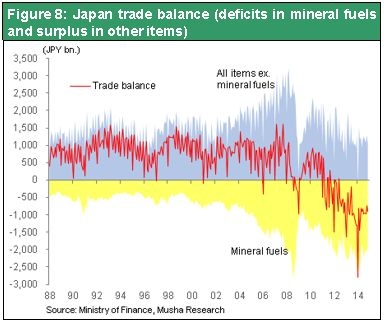

Leaving aside these movements in the market, viewed from a medium-term perspective the decline in the crude oil price is an extremely positive factor for the economies of the developed nations. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York says that a $40 decline in the crude oil price could lead to the transfer of some $1.3 trillion worth of buying power from the oil producing nations to the consuming nations (developed countries). Even if the impact of the decline in the crude oil price is calculated at $1.3 trillion, we think that this would result in a boost of some 0.4% to the GDP of the developed nations on an annual basis. We also think that Japan would be one of the major beneficiary nations from this development.

Japan stocks have been sold off in excessively strong reaction leaving enormous buyback pressure

At the start of the year the Japanese government adjusted its FY 2014 economic forecast to -0.5% and its FY 2015 forecast to 1.5%. The negative growth in FY2014 is due to the fact that ¥8 trillion's worth of purchasing power (equivalent to 1.6% of GDP) has been taken away from consumers by the hike in the consumption tax rate. But FY2015 will see the disappearance of the negative influence of the hike in the consumption tax rate and so the decline in the crude oil price will greatly increase the purchasing power of Japanese households. The impact of a 40% decrease in the price of annual imports of fossil fuels of ¥26 trillion would deliver a positive merit of some ¥10 trillion (or 2% of GDP). By comparison to FY 2014, FY 2015 is likely to enjoy an improvement in terms of special factors of a total of some ¥18 trillion (or 3.5% of GDP) and so the economic outlook is likely to show a substantially brighter aspect. The weak yen merits stored up in the corporate sector mean that we can look forward to the real economy benefiting from rising salaries and wages, increased investment, higher dividends, and other beneficial economic factors.

Moreover, with long-term sovereign bond yields relentlessly approaching zero at present, financial institutions and institutional investors are completely unable to look forward to enjoying any loan deposit interest rates spreads or bond investment income and so whether they like it or not they will be unable to avoid being compelled to invest in stocks. It's probably not worth worrying about the weakness in stocks seen at the beginning of the year, and perhaps it's now time for share prices to start rising sharply.