Feb 16, 2015

Strategy Bulletin Vol.135

Discussions with European Investors

~ The basic stance is positive, but how will Japan’s undervaluation be corrected? ~

Last week, (February 9-13), I visited a number of investors in Europe to exchange thoughts about investment strategies for 2015. I explained two points to these investors. First, investors will only rarely see an investment climate as positive as the one in 2015. Second, quantitative easing, which has become the global standard for monetary policy, will push up stock prices significantly. Almost all investors agreed with my views, although the degree to which they agreed differed somewhat. While all investors take a positive stance on the point that we have rarely seen such a positive climate, this common view always led to the same question: how can we explain the lackluster performance of Japanese stocks, which has no apparent cause?

(1) Why is Japan’s economy in 2015 in the best position since the end of the asset bubble?

Downward pressure from consumption tax hike in 2014 and a boost from declining oil prices in 2015

The first reason is that there are two enormous one-time swing factors influencing the Japanese economy in fiscal 2014 and 2015. In fiscal 2014, one event was the April 2014 consumption tax hike that robbed the private-sector economy of ¥8 trillion (1.6% of Japan’s GDP) of purchasing power. In fiscal 2015, the other event is the drop in the price of crude oil* that has created ¥10 trillion of purchasing power (2.0% of Japan’s GDP). Starting in April 2015, with the consumption tax hike’s negative impact gone, the result will be an addition of 3.6% to Japan’s GDP growth. Never before have we seen swings of this magnitude.

*Japan’s fossil fuel imports totaled ¥28.4 trillion (crude oil ¥14.6 trillion, natural gas ¥7.6 trillion, gasoline ¥2.0 trillion, coal ¥2.1 trillion, others ¥2.1 trillion). Since the prices of most fossil fuels move in tandem with the price of crude oil, a drop of 40% in the cost of crude oil should cut the cost of these imports by ¥11 trillion.

The second reason is the appearance at once of the delayed benefits of both Abenomics and the weaker yen. As the yen declined, Japan’s export volume did not climb. As a result, unlike during previous periods of economic recovery, there was no increase in manufacturing output. This fueled strong criticism of Abenomics as people said it was producing no benefits or was a mistake. Nevertheless, the benefits of Abenomics have been building up in the form of improving corporate earnings on an unprecedented scale. The reservoir is now full. But there is still a drought downstream. There is no doubt that this water will eventually start flowing downstream in large quantities. Through 2014, the favorable cycle that triggered the upturn in corporate earnings was small. But in 2015, the cycle will probably start appearing in the real economy in the form of financial investments such as (1) higher wages, (2) higher capital expenditures and R&D expenditures, (3) higher dividends and stock repurchases, and (4) more M&A activity.

Since the spring of 2014, there have been signs that the long-delayed rebound in export volume is beginning. Japan’s export volume was down 7% in the first quarter of 2014. But export volume was down only 3% in the second quarter and then increased 1% in the third quarter and 4% in the fourth quarter. We can also expect a big improvement in trade volume, partly because companies are moving production back to Japan. Moreover, export volume is improving along with a big increase in yen-denominated export prices. We can therefore expect to see increases in trade statistics regarding both prices and volume. This improvement brings to mind Japan’s fast-growth years of the 1960s and 1970s.

In 2015, Japan’s economy and stock market may be the biggest positive surprise in the world. In January, the IMF lowered the outlook for Japan’s economic growth from 0.8% to 0.6%. This lower forecast has influenced many overseas investors who know little about Japan. Furthermore, people in Japan who have been resolutely against Abenomics regard Japan’s lack of economic growth as proof of the failure of Abenomics. But this flat period is merely a temporary event caused by the consumption tax hike, the delay in the emergence of the benefits of quantitative easing and the weaker yen. It will soon become clear that these negative views are erroneous when Japan starts announcing statistics in the middle of February like 2014 fourth quarter GDP growth (+2.2% on the year) and January 2015 trade figures.

(2) Quantitative easing, now the global standard, will push up developed country stocks, especially in Japan

People who underestimate quantitative easing have all made a critical mistake. They believe that quantitative easing is responsible for falling long-term interest rates and regard this as a bubble in government bonds. In addition, they think that using quantitative easing to supply capital even though there is no demand for investments is causing the historic decline in long-term interest rates in industrialized countries. In fact, low long-term interest rates are not linked at all to quantitative easing.

Why? Without quantitative easing, the economy and stock prices would most likely be far worse than they are now. In this environment, we should expect to see even lower long-term interest rates. So what is the new reality indicated by today’s historically low interest rates? The answer is structural changes that cannot be explained by using business and economic cycles. Furthermore, there is now an extreme imbalance between the supply and demand for money. The cause is both a large supply of capital and very weak demand for capital. Strong earnings are generating the ample supply of capital. On the other hand, it is logical to believe that very low consumption of capital (a dramatic drop in the price of equipment and other investment assets) due to the increase in capital productivity is responsible for the low level of demand. If this is true, the unprecedented downturn in interest rates signifies that an unprecedented industrial revolution is taking place. Consequently, it is a grave error to say that falling interest rates are a sign of the decline of capitalism, which equates to declining profitability. This belief cannot explain the consistently strong earnings at companies in industrialized countries.

This leads to the conclusion that we have reached the point where the actions of people, in other words policies determine the fate of each country’s economy. In the best case scenario, the surplus of capital is used to create demand, which results in economic growth and higher long-term interest rates. In the worst case scenario, excess capital is simply put away. This causes the economic system to collapse because of a rapid deterioration of the system due to deflation and capital in dead storage. Quantitative easing was an experiment for converting surplus capital into demand creation. This was uncharted territory and no one was confident about the result. But today, quantitative easing is viewed as the best policy option. Success demonstrates that the market mechanism (capitalism) is still healthy. Failure would lead to one of two conclusions. One is that capitalism needs to be corrected, meaning that market mechanisms would require government intervention. The other would be to legitimize the hypothesis that capitalism is in decline.

Everyone now is watching the apparent success of the US economy. Jobs are increasing, wages are climbing, the CPI is rising and corporate earnings are strong. Furthermore, the level of financial activity (showing that capital is not in dead storage) at companies is high. All this good news has fueled a long-lasting stock market rally. For 2015, the primary scenario for the US economy is for broad-based growth, rising demand for capital and a slow increase in long-term interest rates. If worries about the end of US economic growth surface, there would be a need for revising capitalism (the main alternative is Keynesian economics). But there is very unlikely to be any need for a revision.

There is no need for investors to study the consequences of quantitative easing this carefully. All they need to think about is how quantitative easing will ultimately influence financial markets. The answer is an inevitable rise in asset prices along with unprecedented opportunities to invest in assets with risk. No one is certain if this is an enormous bubble or a reasonable outcome (sustainable). This is nothing but idle speculation about a matter that can be resolved only by history. The revolutionary aspect of quantitative easing is that the central banks of the US, UK, Japan and Europe have all established the same two guidelines. A pullback from quantitative easing or change of course is unlikely to happen. The guidelines are: (1) a goal of absolutely raising inflation to 2%; and, (2) doing anything needed to achieve this goal. All these central banks are firmly committed to doing whatever is required to reach the 2% inflation target. Taking these actions will inevitably cause asset prices to climb significantly.

(3) Questions from investors in Europe

a) Why did it look like Abenomics had failed? Why will the benefits of Abenomics emerge in 2015?

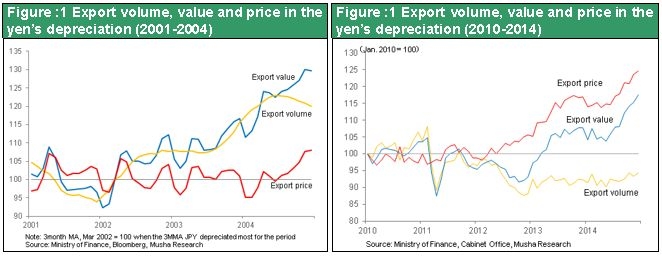

The benefits of Abenomics, which means the benefits of the yen’s decline, did not emerge because of the big structural change in the foreign trade activities of Japanese companies. In the past, a weaker yen supported the economy because of the growth in the volume of exports. More exports meant more production, which fueled a positive chain reaction that fueled Japan’s economic growth. Figure 1 shows how export volume and prices changed during the yen’s previous decline (2001 to 2004). As you can see, export prices did not climb even when the yen started to weaken. That means Japanese cut their dollar-denominated prices. The result was a big increase in export volume. This time, as you can see in Figure 2, there was a large increase in export prices while the volume of exports remained sluggish. Over the past decade, Japanese companies have completely reversed how they respond to a decline in the yen’s value.

Companies in Japan are no longer using prices to compete. When the yen weakens, companies have no need to cut dollar-denominated prices. Yen-denominated export prices rise sharply as a result. Therefore, export volumes are not rising because Japanese companies are not taking part in price-based competition, even when the yen declines. Companies have obviously shifted their business models. Previously, Japanese companies used a model of cutting prices to capture market share from other countries. But now, they rely on a business model of avoiding competition by specializing in technologically superior products. This has not created trade friction. In fact, this shift has produced very strong demand for Japanese products that have the technologies and quality vital to progress in other countries. In China, President Xi Jinping has been a persistent political critic of Japan. But his moves to become closer to the Abe administration can be interpreted as nothing except a sign of China’s desire for access to Japanese technologies.

b) Why are there good prospects for a big wage increase in Japan this year?

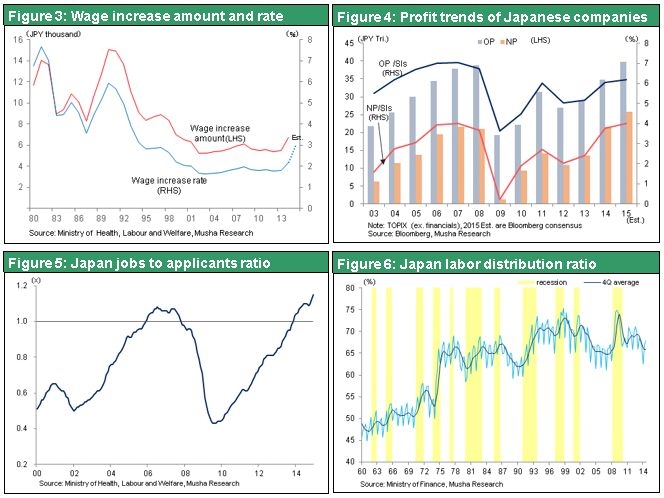

All the right conditions have come together as never before: (1) record-setting corporate earnings; (2) no more need for companies to make up-front investments (to develop technologies and establish global supply chains) because new business models have been completed; (3) consensus has been reached (among the government, business associations, the academic sector and other opinion leaders) that wage hikes are the highest priority for 2015; (4) government support such as tax cuts for companies that raise wages; (5) greater ability of companies to pay higher wages as high-earning baby boomers retire; and, (6) a tight supply of workers (especially for workers with technical skills). Up to fiscal 2013, there were only standard periodic wage increases of 1.6% to 1.7% every year. In fiscal 2014, base wages were raised about 0.5%. In fiscal 2015, there are expectations for a base wage hike of more than 1%. Since Japan’s CPI is expected to increase about 1%, a wage hike of almost 3% would translate into a big increase in real wages that would probably support consumer spending.

c) Selecting sectors for investments

Stock prices will probably start rising in the spring of 2015 as stocks begin to factor in the success of Abenomics. This will be a powerful supply-and-demand market that is propelled by improving fundamentals. Investors will focus on sectors associated with rising asset prices, like financial services, real estate and construction, multinational companies with strong earnings, and sectors associated with domestic demand that have pricing power now that deflation is coming to an end. Due to the outlook for an enormous rally backed by supply and demand, there will probably be large inflows of money from investors who have little experience with Japanese equities. Index investments will grow, which will place priority on monitoring macroeconomic trends. We will probably see particularly strong returns by the stocks of companies in indexes that are also well-known as growth companies. Furthermore, we may see a repeat of the so-called Nifty Fifty stock market that took place in the late 1960s in the United States. This would create a sharp divide between winning and losing stocks in Japan. Companies that work hard on joining the preeminent names among growth stocks will probably be greatly rewarded.

d) Why isn’t Japan’s falling population a problem for the economy?

Let’s look at the negative effects of the declining population. One is a smaller workforce. Another is a decrease in demand. A smaller number of workers can be offset by using automation and computers to boost productivity, thereby lowering the demand for labor. So the problem is how to prevent a decline in demand. We calculate demand by multiplying the population by the living standard and then adding external demand. Therefore, a smaller population can be offset by improving the standard of living. So solving this problem will require a further increase in Japan’s standard of living. Japan has many sectors with significant unmet consumer demand. Examples include living closer to work, more fulfilling activities for free time, and improving the quality of entertainment, medical care and education. There are excellent prospects for overseas demand. Japan has excellent capabilities for supplying higher-quality products and services required by the burgeoning middle class in Asia and therefore well positioned to capture this demand. Tourism and real estate are two sectors that will play key roles.

e) What will trigger the upturn in stock prices? And when will this happen?

Stock prices already reflect expectations about Abenomics. Decisions about altering demand, such as ETF purchases by the Bank of Japan and the shift in GPIF and other public-sector asset management policies, are already factored in. Now everyone is waiting to see if Abenomics and quantitative easing will start a favorable cycle in the real economy and end deflation. The key to everything is fundamentals. If my outlook is correct, we will see a series of statistics starting in late February that show an improvement in fundamentals. I think this will generate substantial momentum for stock prices. Invigorating public-sector funds as well as the massive amount of capital waiting on the sidelines in the private sector and overseas will create an enormous positive shift in the supply-demand balance. I think the Nikkei Average can top ¥20,000 in March or April and may even reach ¥25,000 by the end of this year.

f) Will the growing gap between rich and poor create a problem?

Using quantitative easing to raise inflation to 2% involves using changes in asset prices and foreign exchange rates to increase demand. During this process, there will be an increasing gap between companies and affluent people holding financial assets and all other population segments. However, as long as the market mechanism is functioning, wealth will be automatically dispersed. Eventually, this dispersion will bolster the entire economy. In the United States, there has been a positive chain reaction of growth in jobs and household income. Therefore, people who are frustrated about the wealth gap need to have more patience to wait for the eventual positive outcome.