Oct 25, 2016

Strategy Bulletin Vol.170

Everything is in place for the drive to end Japan’s negative bubble

- The second phase of the Abenomics stock market rally has started

(1) Bank of Japan criticism will trigger a stock market rally

The enormous forces for a negative asset bubble correction

Since the start of Abenomics, the Nikkei Average has surged about 150% from ¥8,000 to ¥20,000. Now the next phase of this rally may be starting. Prospects are increasing for a big move that propels the average to around ¥30,000 by 2020. If dividends remain the same, this rally would bring dividend yields in Japan down from the current 2% to 1%. But even this level is much better than the 0% yield on deposits and long-term bonds. If we assume that dividends will be unchanged and long-term interest rates will stay at zero from now until 2020, there will obviously be a huge opportunity for arbitrage investments. In this case, the market capitalization of Japanese stocks could rise from the current ¥500 trillion (100% of GDP) to about ¥1,000 trillion. If market cap grows over the next four years by an amount equivalent to Japan’s GDP, the economic impact would be immense. We would see a dramatic shift in consumer and investor sentiment, creating an environment for easily reaching the Japanese government’s target of raising the nominal GDP to ¥600 trillion.

Yield curve control is advanced monetary policy and will be successful

Government policies, especially monetary easing, are again the trigger for change. There is no clear verdict yet concerning the Bank of Japan’s decision to control the yield curve by influencing both short-term and long-term interest rates. As a result, the success of this policy would probably be a big surprise. And prospects for success are excellent. Criticism of the Bank of Japan’s actions stems from the fact that neither economics textbook nor the Bank of Japan’s assertions says that this course of action is correct. Can the Bank of Japan determine prices of securities, and should the bank even attempt to do this? Everyone thinks not and it is an irrational position.

The Bank of Japan was well aware of this criticism when the decision was made to embark on its new policy. The bank’s decision was based on the conviction that yield curve control is the best way to end deflation. An enormous perception gap exists between the Bank of Japan and market participants, the media and the academic community. The gap signifies that the two sides have very different views of the fair value of stocks. Consequently, there is now an enormous opportunity for investors.

Asset inflation is the precursor of broad-based inflation

So exactly what does the Bank of Japan want? The answer may be asset inflation. (The Bank of Japan cannot clearly state its goals, since announcing a goal would spark a storm of criticism that would prevent the bank from implementing its policies.) Whenever monetary policy produces inflation or deflation, the first sign of the beginning of inflation or deflation is always a change in asset prices. At the end of 1989, Japan started monetary tightening that immediately caused stock prices to fall. In 1991, real estate prices plummeted. About nine years after these events, consumer price index deflation began in 1998. In the United States, quantitative easing in response to the global financial crisis produced significant upturns in prices of stocks and housing. Higher prices in turn fueled growth in consumer spending. The lesson is clear: It is impossible to create inflation without first creating asset inflation.

This raises the question of whether or not a central bank can set asset prices, which are normally determined by market forces. The Bank of Japan decided that it could control these prices by using quantitative easing. Controlling asset prices would have been impossible with the Bank of Japan’s ¥150 trillion balance sheet immediately prior to the start of the Kuroda-led Bank of Japan’s quantitative easing. But the Bank of Japan’s current balance sheet of ¥460 trillion makes it possible to control prices. Today, the bank’s assets are almost as much as Japan’s GDP and it holds approximately half of all Japanese government bonds. Consequently, the Bank of Japan has taken quantitative easing to a new level by targeting the yield curve and holding long-term interest rates at almost nothing.

Pushing up stock prices is the right policy

Looking only at the current situation, the Bank of Japan’s decision to push up asset prices is correct. Companies in Japan are reporting record-high earnings (value creation) and the country has one of the largest accumulations of capital in the world. Despite these strengths, there has been no economic growth during two decades of persistent deflation. The standard of living has not improved either. The reason is the complete inability of financial markets, which link the economy with the standard of living, to fulfill the function of supplying risk capital.

Japanese companies are giving shareholders a cash return of about 3%, the combination of a 2% dividend and stock buybacks equal to 1% of their market capitalization. On the other hand, cash, deposits and Japanese government bonds all have no return or even a negative return. A massive volume of savings in Japan is sleeping in safe investments with no return. Financial markets exist as an intermediary for directing ample savings to investments, in the process giving investors and households an adequate return. Without this function, an economy cannot operate normally. Furthermore, financial markets cannot function properly unless asset prices are rising. If enabling financial markets to function properly is the key to revitalizing Japan, then the Bank of Japan’s policies are on target.

Bank of Japan critics assume poor demand from deflation as a given

The belief that monetary policy cannot create demand is at the heart of most criticism of the Bank of Japan’s actions. For example, Kyoto University professor Kunio Okina is one of the most strident critics. In a Nikkei Shimbun economics lesson article on October 3 (titled “Evaluation of the overall verification of monetary policy - Preoccupied with justification of framework”), he used comparisons that are easy to understand. He stated that the Bank of Japan’s extreme monetary easing is like building houses ahead of demand despite Japan’s long-term decline in housing demand due to the falling population. The result will be smaller demand in the future. Professor Okina also compared the Bank of Japan’s actions with using a fishing net with smaller openings in order to catch the same number of fish as the total number of fish declines.

However, motivation among Japanese consumers (which equates to latent demand) is low, particularly with regard to housing and life styles. Comparisons with other countries make this very clear. Considerable room for improvements exists. Unfair long-term asset deflation on a scale never seen before in the world was undoubtedly one of the primary causes of this downturn in motivation. (Another cause was the inability of financial markets to function properly for many years.) It is inconceivable that large numbers of economists and opinion leaders could be completely overlooking this fact.

The Financial Services Agency is encouraging risk taking

Radical policies are not limited to the Bank of Japan. Investors must keep in mind the fact that the bank’s actions are just one part of coordinated Abenomics initiatives. The nucleus of these initiatives is expressed by the slogan “shifting from savings (zero-return cash, deposits and Japanese government bonds) to investments (stocks, real estate and foreign currency assets). In a Wall Street Journal interview (August 3, 2016), FSA commissioner Nobuchika Mori said that excessive regulations and tighter capital requirements for banks after the end of Japan’s asset bubble destroyed the willingness of banks to increase risk exposure. Financial markets stopped functioning as a result. Mr. Mori believes that encouraging banks and investors to accept more risk exposure is the highest priority of the financial policy. Furthermore, he does not want other countries to repeat Japan’s mistake.

This momentous shift in the FSA’s stance from limiting risk to encouraging risk is a 180-degree change in policy and also an initiative by Japan’s financial authorities to boost stock prices. Numerous actions are bringing about enormous changes in the supply and demand for stocks. One is the Bank of Japan’s increase in ETF purchases from ¥3.3 trillion to ¥6 trillion. Another is actions by the FSA and other agencies involving the reform of public-sector institutional investors like the Government Pension Investment Fund, Japan Post Bank and Japan Post Insurance. In another step to shift money to assets with risk, Japan established revised corporate governance guidelines and a stewardship code for the activities of institutional investors in 2014 and 2015. All these measures produced a new major source of demand for Japanese stocks: public-sector and private-sector institutional investors in Japan. Stock purchases by these investors will probably produce a powerful stock market rally once selling by foreign investors has run its course.

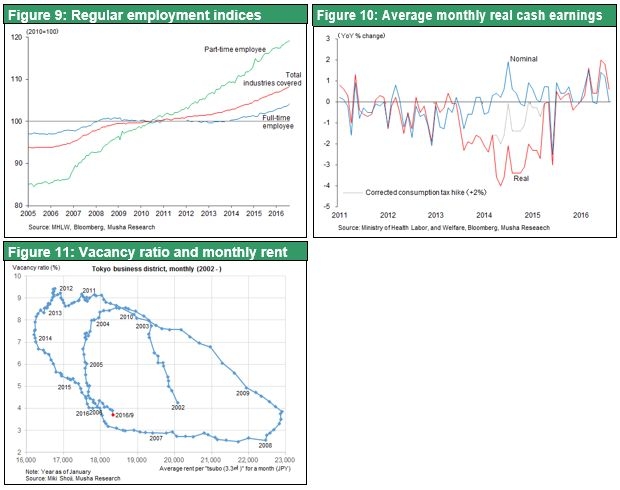

The need to correct Japan’s negative asset bubble (dysfunctional financial markets)

Increasing activities by Japan’s financial agencies regarding the supply and demand for stocks are the target of criticism as a means of manipulating market prices (so-called price-keeping operations). But this criticism is not justified. Changes in stock and bond yields shown in Figure 1 demonstrate this point. Late in 1989, the Bank of Japan popped the country’s asset bubble with an interest rate hike and restrictions on loans. At that time, bonds were yielding 8%. Stocks had an unusually low earnings yield of under 2% (a PER of more than 50 times) and dividend yield of 0.5%. There was clearly an abnormal asset bubble accompanied by rampant speculation. Financial markets were no longer fulfilling their role of properly allocating capital. Therefore, the Bank of Japan had a legitimate reason to enact policies that terminated the asset bubble.

During the next two decades, the Bank of Japan did nothing about a prolonged decline in stock and real estate prices, indicating its tacit approval. Now Japan has reached an extreme negative asset bubble. Stocks have an earnings yield of 6% to 7% and a dividend yield of 2%. Deposits and Japanese government bonds have no yield at all. The gap between these returns is enormous. Existence of this negative asset bubble is proof that Japan’s financial markets are just as dysfunctional today as they were in 1990. The real economy has sufficient returns on investments. But there has been an unjustifiable decline in stock and real estate prices because of an extreme aversion to risk. Consequently, no one can deny that the Bank of Japan has a legitimate reason to intervene in order to correct today’s low asset prices just as the bank did in 1990 when asset prices were too high.

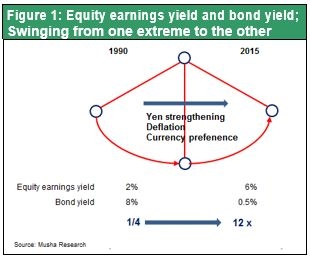

Japan’s abnormal downturn in asset prices

The extended period of assets deflation in Japan is an extremely abnormal phenomenon. As you can see in Figure 2, the value of risk assets in Japan (the aggregate market value of land and stocks) decreased steadily for 20 years from the 1989 peak of ¥3,150 trillion. The downturn finally stopped at ¥1,550 trillion in 2011, a stunning loss of ¥1,600 trillion of wealth. More than half of this loss was caused by unnecessary and excessive price declines. The negative impact on Japanese companies and consumers was severe. Companies and financial institutions had to deal with non-performing loans and asset impairment charges that should not have occurred in the first place. Wages were held down to pass on these losses.

Other countries responded to asset bubbles with completely different policies. The comparison of housing prices in Figure 3 shows that a global housing bubble burst in about 2007. But the subsequent drop in prices ended after only a few years and was followed by a big rebound. Only Japan suffered through a highly unusually 20-year downturn in asset prices. Moreover, monetary policies during that period obviously made a significant negative contribution to this situation. Looking at this issue from the opposite perspective, the correction of unjustifiable asset price alone could boost the value of assets held by the Japanese public by ¥500 to ¥1,000 trillion. This is because Japan has a massive volume of idle savings. Musha Research has been strongly stressing that Japan should adopt this type of action since 2010. Now, the government is finally starting to enact measures to boost asset prices.

(2) Rising interest rates starting in the US and the dollar’s appreciation

US actions will end the global decline in interest rates

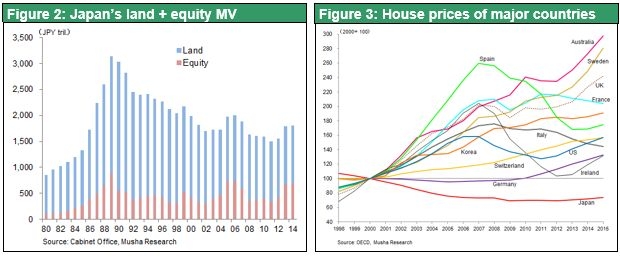

Japan is not the only country with dysfunctional financial markets. A similar problem is happening in other industrialized countries, although on a smaller scale. The historic decline in long-term interest rates is the symbol of this problem. British pound interest rates plunged in response to Brexit. As a result, the United States became the only industrialized country with a meaningful long-term interest rate (Figure 4). However, there has been downward pressure on US interest rates as funds flowed into the country from overseas because of the US economy’s strength. There was even a big drop in yields of junk bonds, emerging country bonds and other risky investments as yield hungry global money is shifting to these assets. Right now, an unprecedented volume of surplus capital is racing around the world in search of a yield. Long-term and short-term interest rates are near zero in all major countries. This narrowing yield gap on different categories of fixed-income assets is preventing worldwide banks from making profits with the traditional source of bank earnings.

Investors should not rush to the conclusion that this situation signals the crisis of capitalism. Earnings at companies are strong. Additionally, although bond yields are low, there are plenty of opportunities in the stock and real estate markets to receive a high return. Stock dividend yields in all industrialized countries are far above government bond yields. Even in the United States, where the economy is performing very well, companies are giving shareholders a 5% return. This consists of a 2% dividend and 3% return by repurchasing stock. The 5% return is more than three times higher than the 1.7% long-term interest rate. Issue is not the ability of companies to generate earnings and create value. The real problem is the inability of financial markets to perform their function of properly allocating the money earned by companies.

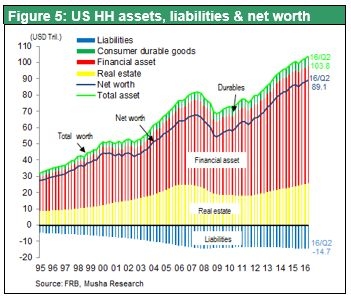

To respond to this unprecedented environment, monetary easing measures have advanced to non-traditional methods that go beyond the conventional thinking of the past. First to enact radical quantitative easing was the United States. By taking this action, the United States succeeded in raising asset prices and became the only industrialized country to avoid the liquidity trap. US financial markets are now functioning properly. Guiding capital to stocks, housing and other risk assets is the immediate goal of non-traditional monetary measures (quantitative easing, negative interest rates, etc.) by central banks. In the United States, non-traditional measures were very effective. After the global financial crisis, US stock and housing prices staged a comeback that greatly improved the volume and quality of household assets. Net assets of households peaked at $68 trillion in 2007, shortly before the collapse of Lehman Brothers. By 2009, these assets had fallen all the way to $55 trillion. However, a subsequent rapid recovery has propelled net household assets to $89 trillion as of the end of the second quarter of 2016. This is six times more than household annual disposable income. Rising wealth enabled households to boost spending. The result is a virtuous cycle consisting of rising asset prices = more household spending (especially for services) = a recovery in jobs and manufacturing = higher corporate and household income. The Fed is coming very close to achieving its dual mandate of full employment and 2% inflation.

More 2017 US gov’t spending points to faster economic growth, a stronger dollar and slowly rising long-term interest rates

Global risk-on investing and yield hunting are gaining momentum for a number of reasons. China’s economy has stabilized for now, emerging country economies are also stable, markets have factored in the impact of Brexit, and the outcome of the US presidential election appears to be clear. The outlook for the US economy after the election is positive. In 2017, the United States will probably see (1) faster growth of the economy and investments, (2) a decrease in idle funds, (3) one or more Fed interest rate hikes, and (4) government spending programs. Investors can expect long-term interest rates to move up slowly as the gap between profit margins and interest rates narrows. Opportunities for yield hunting will decrease as a result. If this actually happens, a substantial volume of surplus money from around the world will flow to Japan once the yen’s appreciation comes to an end. In 2017 and 2018, the United States will probably complete its demonstration to the world of how to eliminate the risk of deflation: quantitative easing = higher asset prices = resumption of economic growth = Fed interest rate hikes and rising long-term interest rates. This will create hopes for Japan, European countries and other developed countries to follow this example.

Another era of Keynesianism has started

In the United States, monetary measures proved to be effective. Now it is almost time to switch to fiscal measures. Both major-party US presidential candidates have agendas that include aggressive spending programs backed by surplus capital. Several factors have joined to produce a perfect environment in the United States for Keynesian measures. Most significant are the country’s aging infrastructure, the decline of the budget deficit from 10% of the GDP (2010) to the 2% level (2015) and historically low long-term interest rates. This fiscal and monetary cycle for surplus capital will probably raise long-term interest rates very slowly and increase the potential growth rate of the US economy. If this happens, investors should expect US stock prices and the dollar to move up for a long time.

There is good reason to adopt a positive medium to long-term outlook while keeping an eye on risk factors associated with China. Stop-gap fiscal and monetary measures of many types in China have succeeded in preventing an economic stagnation. Taking these actions has created more difficulties for China from a long-term perspective. But potential sources of problems have been contained for the time being. China has limited the decline in foreign exchange reserves by tightening capital controls. Consequently, a sharp drop in the yuan’s value is very unlikely to occur. Because of these reasons, at least for now, there is very little risk that China will spark a global financial crisis.

(3) Full employment and other solid economic fundamentals in Japan set the stage for a big stock market rally

Extremely pessimistic market sentiment is a sign of an impending rally

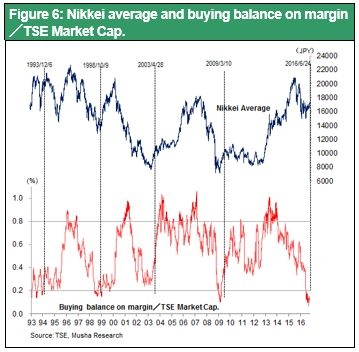

Investors who buy Japanese stocks have been extremely averse to risk despite the global stock market rally. The drop in unsettled arbitrage buying position to a historic low is the most significant evidence of this risk aversion. People have become prejudiced against Japanese stock investments. However, as is evident in Figure 6, Japanese stocks have always rebounded strongly immediately after the unsettled buying balance of arbitrage trading declined to historically low levels. People have been embracing pessimism for no legitimate reason because economic fundamentals are sound. Consequently, everything is in place in terms of supply and demand for stock prices to begin staging a comeback.

The GDP growth rate surpassed interest rates for the first time in 20 years

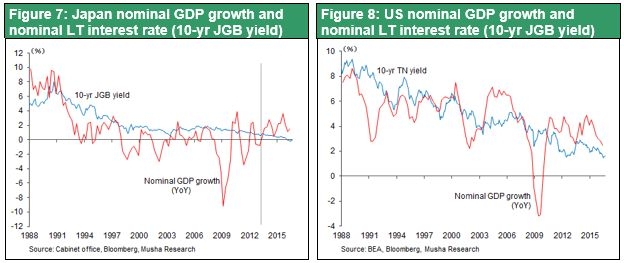

A perfect environment now exists for the success of the Bank of Japan’s new monetary policy. As I stated in the previous strategy bulletin, the most critical factor is the relationship between the nominal GDP growth rate, an indicator of the economy’s health, and the nominal long-term interest rate, which is the cost of economic growth. (The relationship between nominal growth rates and nominal interest rates is the same as for real growth rates and real interest rates.) As you can see in Figure 7, there is a dramatic change between the period before Abenomics and quantitative easing and after the start of these policies. During the two decades prior to Abenomics (1992-2012), interest rates were consistently higher than the GDP growth rate. This clearly demonstrates that interest rates (credit) were holding back economic growth. But this relationship has been reversed since 2013. Now interest rates (credit) are unmistakably contributing to economic growth. As long as the GDP growth rate is higher than the interest rate, there will be a favorable environment that rewards risk takers and supports economic growth.

In the United States, which the sound creation of credit continues and deflation was avoided, the GDP growth rate has been consistently higher than the interest rate. The relationship was reversed only briefly during the global financial crisis. The big difference in the levels of Japanese and US interest rates in relation to the strength of economies of these countries may have been the cause of Japan’s deflation. In this case, Japan has already eliminated this source of deflation. If Japan can keep its GDP growth rate above the long-term interest rate, which has been the case since 2013, we should see a positive cycle driven by the return of risk-taking sentiment and rewards for risk takers.

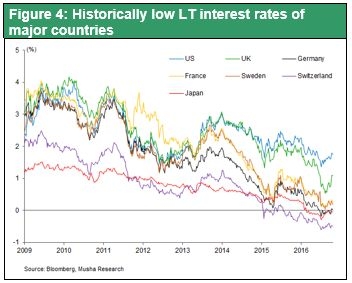

All fundamentals are pointing upward

Japan’s fundamentals are improving steadily. The number of jobs has been climbing since 2013 and the supply of workers is tight. Due to this situation, wages have finally started moving up (Figures 9, 10). Real estate rents have started to rise with improving real estate supply-demand dynamics. In addition, corporate earnings are likely to be sound now that the yen’s strength is coming to an end. There are still more reasons for a positive outlook: the Japanese government’s ¥28 trillion spending plan, the end for now of economic problems in China, the end of the decline in commodity prices, bottoming out followed by a slow recovery in world trade, and the health of the US economy. For these reasons, most economists forecast a recovery in Japan to real GDP growth of about 1% (the ESP forecast is 0.9%).

Furthermore, now that the yen is no longer appreciating and the price of crude oil is climbing, Japan’s CPI, which was briefly negative, will probably increase at a rate of about 1% in 2017.

The new US president will create a favorable geopolitical environment for Japan

The majority of foreign exchange rate watchers anticipate a stronger yen. However, almost all of these people are also very pessimistic about Japanese stocks. Therefore, if Japanese stocks start moving up, the higher stock prices would be a reason for risk-taking and a weaker yen. In addition, as I explained in the previous strategy bulletin, the next US president will probably not allow the yen to appreciate beyond a certain level for geopolitical reasons. For these reasons, the yen’s appreciation that began about 10 months ago has probably come to an end. Weak yen and strong Japanese stock price will provide the condition for Abenomics to succeed.