Mar 21, 2017

Strategy Bulletin Vol.178

A global rally fueled by robust economies has started

- Japanese stocks will join the rally now that worries about a stronger yen have dissipated

(1) Simultaneous economic strength worldwide is emerging

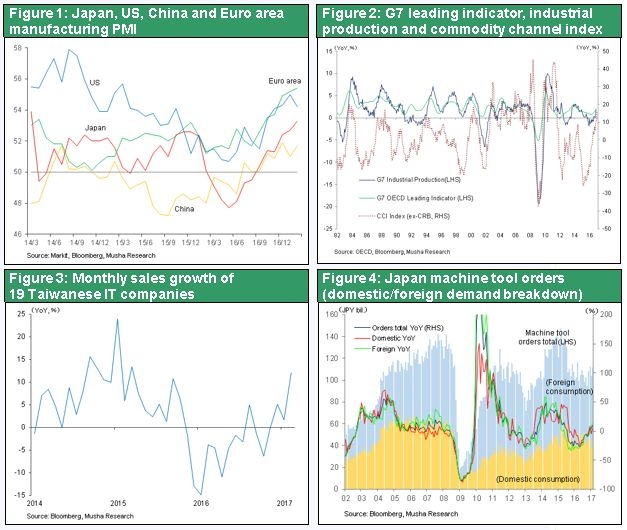

Many indicators point to the beginning of a worldwide economic upturn (Figure 1). The manufacturing purchasing managers’ index is moving up in the United States, the eurozone, China, Japan and all other areas of the world. Commodity prices are climbing and the recovery in the price of crude oil is supporting a rebound in resource-related industrial sectors. A recovery in the high-tech cycle is another important aspect of the current economic upturn. Rapid growth of sales at Taiwan IT companies is a key indicator of the health of the high-tech sector, which is very sensitive to changes in the economy (Figure 3).. The high-tech sector is benefiting from the completion of inventory adjustments, an improvement in the product cycle, strong growth of high-tech investments in China and other events. In addition, Japan machine tool orders are recovering for domestic and foreign demand, indicating signs of a global capital investment boom (Figure 4).

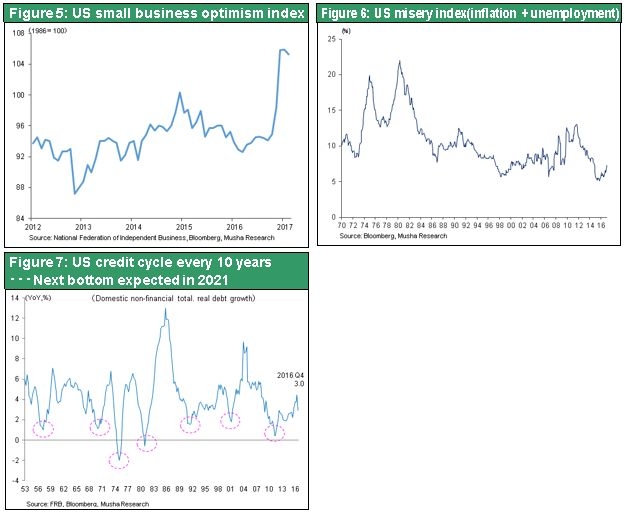

Improving economic sentiment in the United States is particularly noteworthy. The economic optimism index of small and midsize companies, which account for more than 80% of US jobs, has surged due to high expectations about policies of the Trump administration. Furthermore, the US misery index (sum of the unemployment rate and inflation) has never been lower. These numbers demonstrate that the United States is holding down inflation despite being at full employment. As a result, there is no need for excessive monetary tightening.

The decline in the US budget deficit to below 3% of GDP is another positive development. A smaller deficit will allow the United States to cut taxes and invest in infrastructure. Furthermore, deregulation involving energy and financial services will stimulate business activity. By the 2018 US interim election, the US could very well have an economic growth rate of more than 4%. In fact, prospects are good for this expected economic boom to continue throughout President Trump’s first term.

The global economy has been expanding for 90 consecutive months following the global financial crisis. There are concerns about the economy because the length of this growth has reached about the average for postwar upturns. But there is no need to worry. In 2015 and 2016, the world has experienced a manufacturing recession, a corporate earnings recession and a growth recession. Now the global economy is starting to recover from these recessions. In addition, as you can see in Figure 7, the US 10-year credit cycle shows that we can expect the next bottom in 2021. This is another sign that economic growth will probably continue for some time.

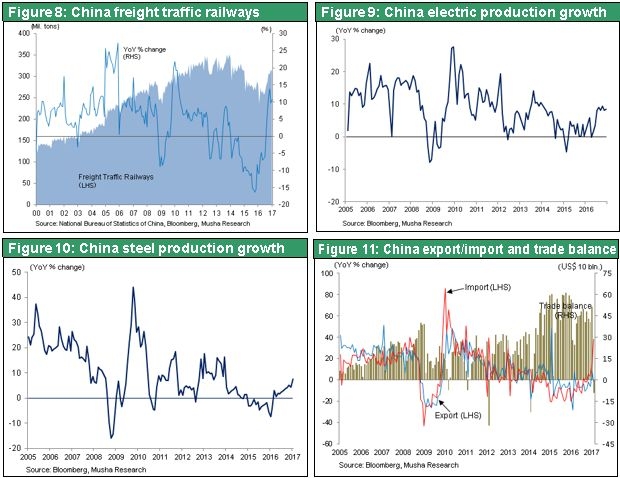

A strong economic rebound is happening in China, too. At the March National People’s Congress, the 2017 GDP growth target was cut from 6.7% to 6.5%. However, microeconomic indicators like railway freight volume, electricity consumption, crude steel production, and imports and exports are up significantly. These indicators fell into negative territory in 2015 and early in 2016 amid mounting worries about a financial crisis. But massive government spending for infrastructure projects and real estate investments backed by monetary easing have produced a big increase in China’s economic activity. Doubts exist about the soundness and sustainability of this upturn. But there is probably no need to worry about a slowdown for the next year or two.

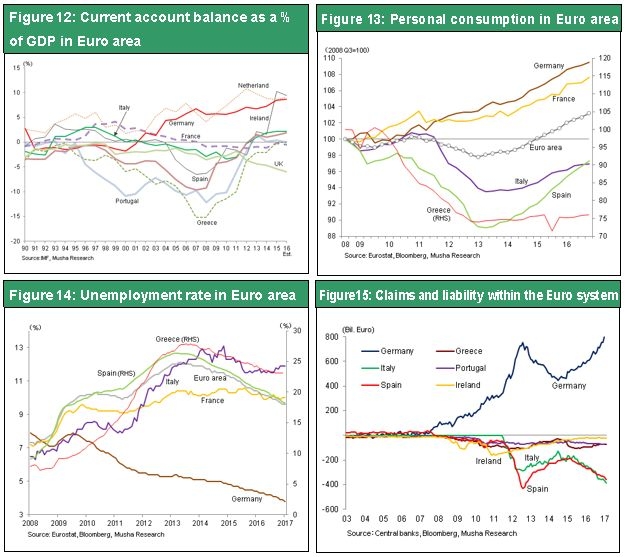

Brexit has sparked a rise in populism. In the eurozone, there are worries about the sustainability of the EU and the euro. But consumer spending and jobs in the eurozone are climbing and some countries are boosting their GDP growth forecasts. Improvements in the real economy may suppress support for populism that threatens the solidarity of the eurozone. Furthermore, monetary easing and the supply of liquidity by the ECB have been successful (Figure 15).

Worldwide economic health is being accompanied by an ample supply of money for investments and liquidity. The result is a Goldilocks environment where everything is just right. This is an ideal time for risk-taking. No one should be surprised that stock indexes in the United States, Germany and Britain are all near their all-time highs.

(2) Worries about a stronger yen that held back Japanese stocks are excessive

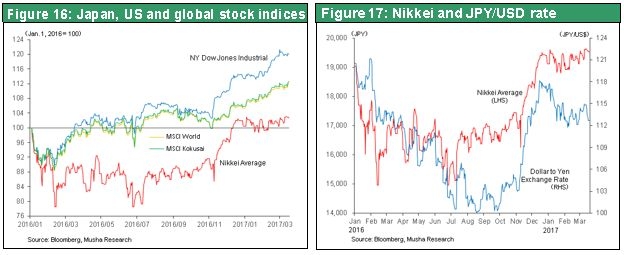

In the midst of record-high stock prices elsewhere, the Nikkei Average has been stuck in a trading range of ¥19,000 to ¥19,500 for the last three months. Worries that the Trump administration will create trade friction with Japan are the cause. Investors fear that this friction may create unfair upward pressure on the yen (Figures 16, 17). However, fundamentals as well clearly show that the current environment is conducive to a stronger dollar. The US economy is now the strongest in the world and the recent third rate hike by the Fed demonstrates that monetary tightening is under way.

This discussion leads to the question of why the Trump administration wants to see a weaker dollar. There are several possible reasons. One is that a weaker dollar would reduce the trade deficit by making US products more competitive. But the laws of economics tell us this is wrong. Trade deficits and international payment balances are determined by the balance between investments and savings in individual countries. A country cannot change these deficits and balances by altering foreign exchange rates. Therefore, this objective of a weaker dollar will probably disappear eventually.

Enticing companies to build factories in the United States is a second possible goal of a weaker dollar. But this goal as well is off target. The start of trade protectionism by the United States would result in the market factoring in a future decline in the US trade deficit. This would most likely make the dollar stronger rather than weaker. Furthermore, there is talk of imposing a border tax. If imports from Mexico are taxed at 20%, the prices of Mexican products would become less competitive. However, markets would be looking ahead. The result is likely to be a weaker peso and not a weaker dollar. This would make prices of US products less competitive from the standpoint of Mexico. Consequently, there is no economic rationale for expecting a change in foreign exchange rates to bring factories back to the United States. So any attempt to weaken the dollar for this purpose would probably end in failure.

The only possible reason that remains is that the United States wants a short-term decline of the dollar as a threat or bluff for dealing with other countries. Currency exchange rates can be used as a threat in order to obtain international trade concessions. This is the sole logical reason for the Trump administration to talk about a weaker dollar. If this is true, then there is no need to take these words very seriously.

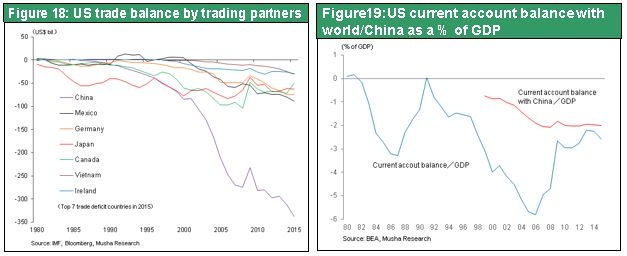

So just why does the United States need to utilize such an obvious bluff? The answer is that the Trump administration probably wants to create a new framework for global trade. Japan, Mexico and Germany have been singled out regarding trade issues. But the real enemy is China. By using unfair actions like copying and stealing intellectual property, China has become much more competitive. The country has now reached the point of challenging the United States for global hegemony. Perhaps the United States wants to use exchange rates as a means of holding down China’s excessive global profile. The United States has a $350 billion trade deficit with China, which is about half of the total US trade deficit. Combined, the US trade deficits with Japan, Mexico and Germany, all targets of frequent US criticism, are only about one-fifth the size of the deficit with China. In addition, the US current account deficit has dropped to 2.6% of GDP from the peak of 5.7% in 2006. The bottom line is that the trade deficit is not a serious problem at all for the United States.

Peter Navarro, director of the National Trade Council, believes that China’s excessive economic presence is the reason for China’s growing influence in the world. He also thinks that extremely unfair activities are supporting this economic presence. Mr. Navarro therefore believes that preserving the current global order will be impossible without correcting this problem. He says this will inevitably result in war between the United States and China. Avoiding a war will require either US capitulation to China’s military strength or preventing China from becoming a military superpower by halting its current economic free ride. These are the only options. Apparently, Mr. Navarro wants to use exchange rates to limit China’s economic clout. To accomplish this goal, the United States will have to create the appearance of acting with fairness by singling out other countries too as targets.

The people of Japan have been experiencing the negative effects of trade friction and a strong yen since the second half of the 1980s. The public is afraid that they may have to endure these difficulties again. But this is absurd. The possibility of the yen rising beyond ¥110 to the dollar is extremely small. Another important point is that Japanese companies are more resilient to a stronger yen due to the big change in the nature of their export activities.

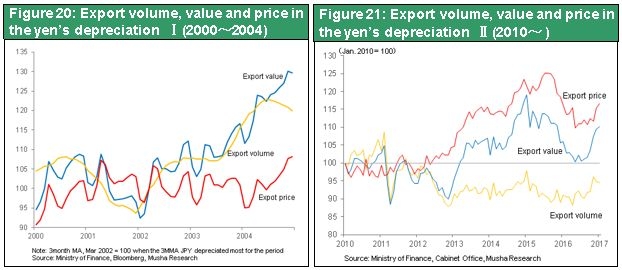

During past periods of the yen’s depreciation (such as the decline that began in 2000, as shown in Figure 20), Japanese companies lowered their dollar-denominated export prices. There was no change in yen-denominated prices. The aim was growth in the volume of exports. Recently, Japanese companies have not revised dollar-denominated prices when the yen depreciated (the decline that began in 2010 in Figure 21). That translates into higher yen-denominated prices. Companies are no longer seeking to use lower prices to increase export volumes. In other words, Japanese companies haveare shunning price-based competition by focusing on products with technologies and quality that overseas competitors cannot beat. This approach means that export volumes do not climb when the yen weakens. But companies benefit from higher yen-denominated prices. Once more people become aware of this practice of Japanese companies, the Trump administration will realize the futility of attempting to use exchange rates as a response to trade friction with Japan. Upward pressure on the yen in forex markets will probably decline if this happens.

All of these points indicate that any criticism of Japan by the United States will be minor. That means an increase from the current level of upward pressure on the yen is very unlikely. For these reasons, Japanese stocks will probably no longer lag behind stocks in other countries. Investors can expect to see a rapid resurgence of Japan’s stock markets.