The fiscal campaign triggered by the Greek crisis

Japanese Prime Minister Naoto Kan has proposed a hike in the consumption tax to 10%, stating that Japan will become the next Greece unless something is done. The crisis in Greece has been beneficial with respect to focusing attention on the need to cut government budget deficits. The public can easily see this problem. Even analysis of the causes of the Democratic Party of Japan’s defeat in recent Upper House elections included media reports of comments by political observers that the Japanese public understands the need for a higher consumption tax. Perhaps the public’s crisis mentality is a good thing. But this is a problem if people become overly pessimistic and cautious. Mistaken pessimism of the Japanese public may even be the reason that Japanese stocks alone have been lagging behind the global rebound in stock prices.

A massive deficit is the only similarity with Greece

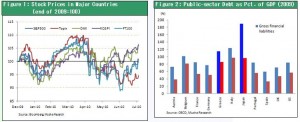

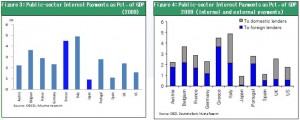

It is inconceivable that Japan will go down the same path as Greece merely because Japan has a huge budget deficit, too. Many experts and media companies are pointing to the similarities between Japan and Greece. But they are all off target. Japan and Greece have only one thing in common: a massive budget deficit. As Figure 2 shows, Japan is the world’s biggest debtor, even more than Greece, in terms of its public-sector debt as a percentage of GDP.

Interest burden is smallest in Japan and highest in Greece

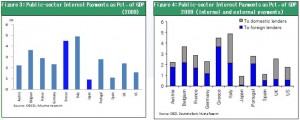

But Japan is exactly the opposite of Greece with respect to two key points. First is the government’s interest payment burden. Japan has the world’s lowest level of public-sector interest payments in relation to its GDP and Greece has the highest. In fact, the ratio in Greece is five times higher. The cause is obviously Japan’s very low interest rates. Nevertheless, there is an enormous gap between the likelihood of a default in Japan and in Greece. In addition, foreigners hold more than 80% of Greek government debt. In Japan, this percentage is only about 4%, demonstrating the country’s much lower dependence on overseas investors. There are concerns about the Japanese government becoming unable to finance its debt if long-term interest rates rise due to a resurgence of inflation, plunge in the yen’s value or other event. But these fears are also pointless. In Japan, private-sector interest income will increase at the same pace as an upturn in interest payments on government bonds. Higher interest income would probably make a big contribution to economic growth in Japan. Right now, the Japanese public is paying the price for the country’s debt. This is because extremely low interest rates have forced the people to accept exceptional low returns, on the other hand have made the government to have cheap finance.

Growth in ULC and wages are lowest in Japan and highest in Greece

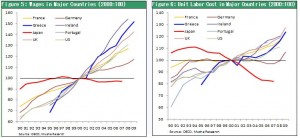

The second key difference between Japan and Greece is the gap between increases in wages and unit labor costs (ULC). Japan has recorded the lowest growth rates (biggest declines) in ULC and wages during the past 15 years. During the same period, Greece had the highest growth rates. The reason is that Greece has the most overpaid workers in the world in relation to what they actually made. Japanese workers rank first in the world in terms of being underpaid in relation to their actual making.

What is the significance of this difference? It shows that the Japanese and Greek economies are suffering from precisely the opposite problems. In Greece, productivity gains lagged behind wage increases and this created excessive demand. In Japan, wage increases lagged behind productivity gains and this caused demand to shrink. In other words, high wages in Greece sparked excessive consumption while low wages in Japan resulted in inadequate consumption. Obviously, precisely opposite remedies are called for. Greece must cut back government spending and enact other austerity measures to hold down wages and consumption. But Japan needs to adopt expansionary monetary and fiscal policies in order to support growth in wages and consumption.

Should the sudden emergence of the Greek debt crisis be used as an excuse for Japan to give inordinate attention to the budget deficit and push behind the urgent need to end deflation to the back burner? This would clearly be a big mistake.