Mar 19, 2020

Strategy Bulletin Vol.248

Analysis of the Pandemic and Market Panic and the Outlook

A state of emergency in the US and Europe, but the end of China’s outbreak may be in sight

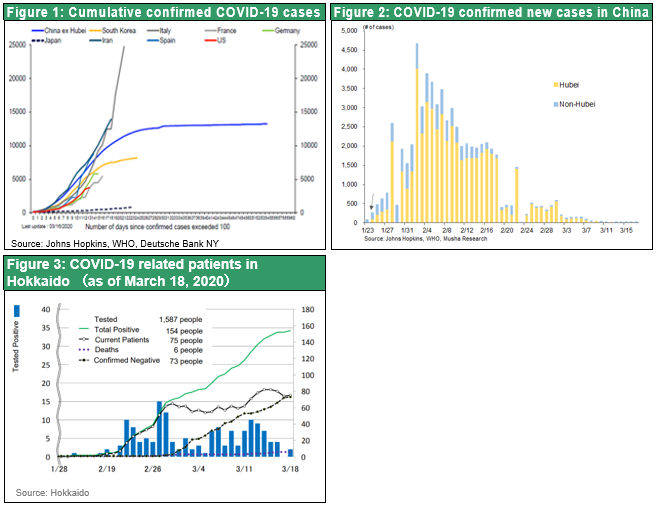

The COVID-19 pandemic that originated in China has reached Europe. Italy and Spain are experiencing a Wuhan-like collapse of their healthcare systems. The United States and Europe are now both in a state of emergency. However, once this pandemic, which is a type of natural disaster, has been overcome, we can expect to see financial markets stage a sharp recovery from their extremely low levels. China, South Korea and Hokkaido were among the first serious outbreaks. Judging from the progress of the outbreak in these places, the number of infections in Europe should peak within one or two months. After that, the number of people who have recovered from COVID-19 will exceed the number of those currently infected. But now, governments worldwide are using emergency declarations to begin taking whatever actions they believe are needed.

Japanese stocks are in the margin of safety

The key point is that stocks are now extremely undervalued in the wake of panic selling that slashed prices by about 30% in less than one month. Japanese stocks have a dividend yield of 3.1% and a PBR of 0.9. At this level, stock prices have factored in the continuous loss of corporate value for many years into the future. In fact, stock prices have fallen to a level consistent with the margin of safety, a concept created by Benjamin Graham, whose ideas have guided Warren Buffett. In other words, stock prices are now absolutely undervalued regardless of what happens in the future.

(1) When will we win the war against COVID-19?

Everything depends on stopping new infections

When and why will stock prices stop falling? Both answers depend on the ability to stop the spread of this virus. The basic scenario calls for new infections to wind down in the first half of 2020, leading to a second half economic recovery and higher stock prices. Opinions differ about whether the recovery will be slow or fast. But a fast recovery is probably more likely for several reasons. First, the sudden drop in manufacturing will create inventory shortages. Second, pent-up demand will be released once the crisis abates. Third, the recovery will be fueled by the all-out measures of governments in response to this crisis. However, the recovery could be slow if COVID-19 cannot be completely contained. In this case, there may be a negative cycle as demand that disappeared during the crisis comes back slowly, many companies fail and other problems occur. Consequently, the outcome of this pandemic will ultimately depend on the ability to stop the virus and on the actions taken by countries worldwide.

Lessons Learned from China, South Korea and Hokkaido

Locations where the outbreak happened first, such as China (where there are very few new infections), South Korea (where new infections have declined sharply) and Hokkaido, can give us insights about the drastic actions taken by countries in Europe. Figure 3 shows the number of people infected and the number who have recovered in Hokkaido. The number of people infected stopped climbing about two weeks after the emergency declaration. Over the following one to two weeks the number of people who caught COVID-19 and recovered started to climb. Now, a few weeks later, the number of people infected is remaining flat. COVID-19 is clearly highly infectious, but 80% of these infections produce only mild symptoms. In the 20% of cases that are serious, about half of these individuals recover quickly. Most of the people who die are elderly or had a preexisting condition. Furthermore, the death rate is 1% to 2%, which is low compared with the death rates of the bubonic plague and cholera, diseases believed to be incurable, SARS (10%) and MERS (35%).

(2) When will stock prices hit bottom?

The fastest ever drop in stock prices

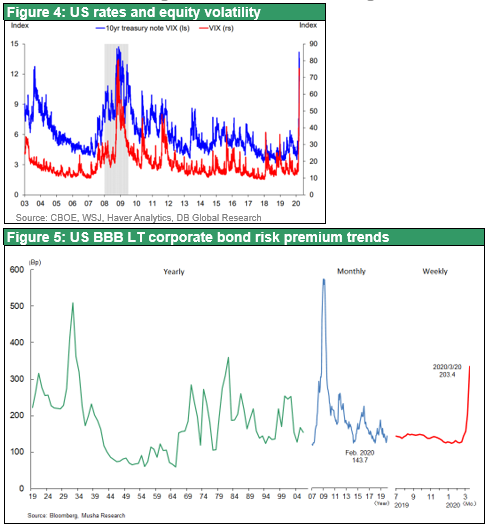

The 30% plunge in global stock prices over only three weeks set a new record for speed. As Figure 4 shows, the volatility index (VIX) surged to a level that matched the all-time high recorded during the Global Financial Crisis. Nevertheless, the economy has not collapsed and there has been no full-scale panic in financial markets overall. Furthermore, the risk premium in credit markets is steady (Figure 5) and there has been only a limited increase in the financial stress index.

Why did stocks fall so much?

- Unexpected, no defense – Every US recession in the postwar period was triggered by monetary tightening to fight inflation. This may become the first recession with a different origin.

- Uncertainty – There is no way to know when this crisis will end because the enemy is a natural entity (a virus).

- Vulnerability of markets – There was too much conceit in financial markets. Pessimism that existed until the middle of 2019 had largely disappeared by the beginning of 2020. As a result, the majority of investors had risk exposure that they had willingly chosen to take on.

- A vicious cycle – During the downturn, there was a steady flow of selling as investors suffered losses and then sold holdings in order to avoid risk and maintain their liquidity.

Investors underestimated the magnitude of volatility

The vulnerability of markets is probably the most important of these four points. Investors are not sufficiently aware of the fact that we live in an age of unprecedentedly high volatility. There are several generally accepted explanations. First is the existence of a massive volume of surplus capital and funds available for investments. Second is the consolidation of global funds into a single pool. Investors with enormous assets are able to instantly shift funds among different asset classes. Third is the growth of speculation in an environment of extreme monetary easing and low interest rates.

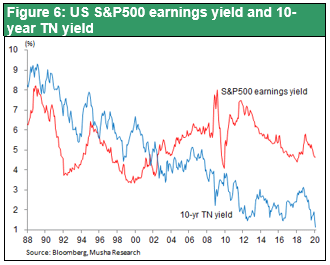

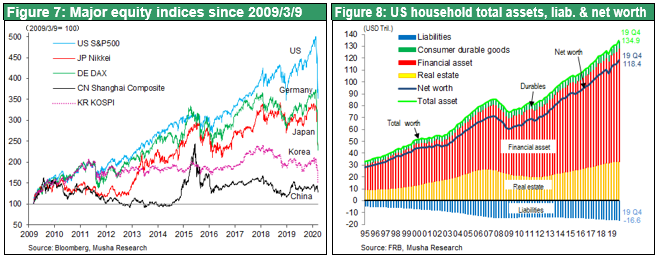

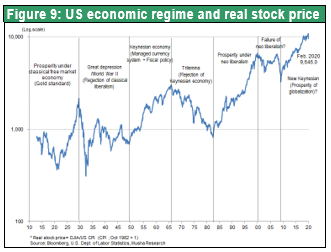

An age of high volatility created by abnormally high surplus equity returns

All three explanations are correct. However, the fundamental cause of rising volatility is probably the abnormal increase in the risk premium of stocks. As Figure 6 shows, prior to the collapse of the IT bubble in 2000, the earnings yield of the S&P500 was about the same as the 10-year Treasury yield. Furthermore, these two returns moved up and down in tandem. There was no barrier between stocks and bonds in US markets. As a result, investors were constantly moving their money back and forth between stocks and bonds for arbitrage. After the end of the IT bubble in 2000 and then the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, there has been a big gap between stocks and bond yields. Moreover, this large gap has become firmly established due to the significant decline in the 10-year Treasury yield.

Why did a disparity of this size exist for so long in a market that should be rational?

Stock earnings yield of 5.2% > Treasury yield of 1.5%

The answer to this question is that stocks with a high earnings yield also have substantial investment expenses that apply exclusively to these stocks. These expenses can be viewed as a means of lowering the final return on stock investments to match the Treasury yield. The investment expense is the volatility.

Stock earnings yield – Cost of volatility = Treasury yield

Consequently, the higher return of stocks in relation to bond yields is offset by the cost of volatility associated with stock investments. We can conclude that a larger gap between the stock earnings yield and the Treasury yield equates to higher volatility. If interest rates are low and the surplus return for stocks is high, investors are likely to raise their leverage in order to seek even bigger gains on stock investments.

High returns generated by highly leveraged portfolios can be wiped out by the big swings in financial markets that happen from time to time. This cost of volatility appears to incorporate a mechanism for redistributing the surplus return of stocks to a variety of market participants, financial institutions and individual investors. This mechanism may very well be responsible for dramatic market sell-offs, such as the February 2018 volatility shock, that cannot be explained by fundamentals.

High volatility sets the stage for a strong rally after a big drop

The good news is that volatility has no relationship at all with the intrinsic value of stocks or stock prices level itself. Market downturns triggered by volatility set the stage for a powerful rebound. Stock prices plunged in February and October 2018 and both downturns were followed by a rapid upturn. Less than one year later, stock prices surpassed the high prior to the downturns. This record-setting drop in stock prices may have these same characteristics. If so, we can expect to see a fast and steep rebound in stock prices once the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic is behind us and signs of an economic recovery begin to emerge.

(3) Assessment of risk factors and explanation of Japan’s position

The preceding points demonstrate that this unprecedented drop in stock prices will not produce a severe crisis. Prospects are good for a rebound that offsets the decline somewhat within a relatively short time. However, we need to examine the risk factors that could stand in the way of this rebound. When people look back on this period some time from now, they may view the pandemic as an event that was a historic turning point in our life styles, business models and the global order.

Government initiatives have failed to prop up stocks; what will establish a bottom?

Economic measures do not have any direct effect on this crisis because the enemy is a virus. The objectives of government actions are merely to ease the symptoms of the pandemic and achieve a recovery sooner. Avoiding a recession is not the goal. Nevertheless, there is a critical need for quick monetary and fiscal measures involving the severe decline in the cash flows of households and companies. Once governments have established adequate safety nets and there is no longer the threat of a deep recession, stock prices will probably stop falling. In the Untied States, the Fed took emergency actions to back up liquidity by cutting its benchmark federal funds rate by a full percentage point, resuming quantitative easing and buying commercial paper, among other measures. There is also talk about other measures on a massive scale, including a $1 trillion fiscal stimulus plan, sending every adult a $1,000 check, and extending financial assistance to airlines and other companies in industries damaged by this pandemic. But is this enough? People are also wondering if these expenditures will be approved. This is why confidence in the safety net will play a key role in establishing a bottom for stock prices.

Are the preservation of stock market capitalism, the highest priority, and a stock price recovery possible?

Stock market capitalism in the United States is a virtuous economic cycle underpinned by rising prices of stocks and other assets that greatly increase the net assets of households and generate higher consumption. Is the pandemic a threat to this capitalism? As of the fourth quarter of 2009, which was the bottom of the Global Financial Crisis, US household net assets were down to $49 trillion. But household net assets then increased $64 trillion (three times the US GDP) over the next 10 years to $113 trillion as of the second quarter of 2019.

Stock market capitalism is possible because of quantitative easing, a new scheme for essentially printing more money in order to create money in amounts that match the tolerance of stock and other financial markets. Governments are currently taking quantitative easing to an even higher level. No obstacles stand in the way of quantitative easing and other government actions to increase support for stock market capitalism. Furthermore, the animal spirits of US investors are deeply rooted and cannot be easily destroyed. If the policies I have just outlined are successful and the economy returns to normal by the end of this year, a relatively short time, stock prices will be able to recover.

Achieving this recovery will require massive public-sector expenditures. If governments continue to make large expenditures, we could see the emergence of a framework, which could even be called a New Keynesian Model, in which the public sector is the driving force behind the creation of demand. However, long-term interest rates (government bond yields) may hit bottom and start climbing in response to the growth of public-sector debt for these expenditures. If this happens, there could be a big decrease in the surplus return of stocks (stock earnings yield – government bond yield). A smaller surplus return would probably have the effect of weakening any rebound in stock prices and reducing volatility.

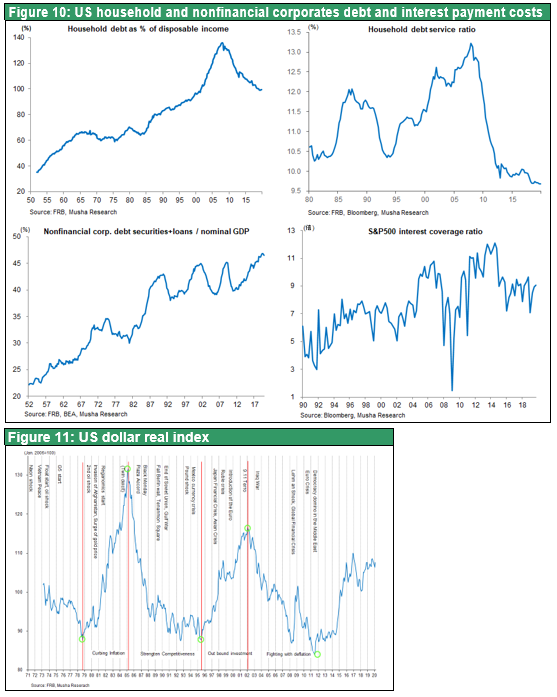

How does this differ from the Global Financial Crisis?

The cause of this stock market downturn is a temporary economic shock triggered by a natural disaster. This is fundamentally different from the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), which was the result of the use of excessive debt for excessive risk-taking. As Figure 5 shows, the risk premium during the GFC became even higher than during the Great Depression. But this premium has not increased significantly during this crisis. After the GFC, there was a big decline in excessive debt of US households (ratio of debt to disposable income), as shown in Figure 13. At the same time, corporate debt increased considerably as companies bought back their stock. Despite the growth of debt, the ability of companies to support this debt (interest coverage ratio) is sufficient because of falling interest rates and rising earnings. Furthermore, repeated stress tests have demonstrated that the balance sheets of financial institutions are sound.

One similarity with the GFC is concerns about international finance due in part to worries about liquidity drying up because of the plunge in the price of crude oil. Liquidity problems would raise demand for dollars (cash) and briefly cause the dollar to strengthen. As Figure 11 shows, the dollar’s appreciation did not last long during the GFC as monetary easing and quantitative easing subsequently made the dollar weaker. However, this time may be different. An upturn in interest rates sparked by growth of the US government budget deficit might cause the dollar to appreciate for a long time.

This crisis will probably increase US hegemony. Many factors make a further increase in the global stature of the United States appear to be inevitable. Examples include the ability to use the dollar to control the global financial system, US control over industrial information, and the containment of China, which is vying with the United States for hegemony. This hegemony will probably back up the strength of the dollar.

The US-China confrontation will become even more heated

During the GFC, enormous public-sector spending in China made this country a source of demand amid a shortage of demand worldwide. These expenditures dramatically increased China’s role in the global economy. This time as well, China will probably be the first country to return its economy to normal. The COVID-19 outbreak happened in China first and the country responded with decisive monetary and fiscal measures. As a result, the global supply chain centered on China will probably be restored, at least for a while.

Events after this supply chain restoration are likely to differ completely from what happened after the GFC. The whole world believes that China (and even more so the totalitarian regime of President Xi Jinping) is primarily responsible for this pandemic. The United States has been extremely critical of how this regime attempted to cover up the outbreak and report fabricated information. The US-China confrontation will probably increase because of these events. Although a preliminary deal was reached at the end of 2019 with US-China trade negotiations, this problem is likely to erupt once again. President Xi is increasing his power in China in order to rebuild his regime. Taking these actions will probably serve only to further isolate China on the global stage. For example, European countries thinking of buying 5G equipment from Huawei may decide to use different suppliers. Consequently, these events may become a turning point for China as its economic power declines due to the worsening of already excessive internal debt, declining returns on capital and other problems.

A dramatic increase in the superiority of Japan’s positioning

In the international division of labor, Japan is one of only a few countries that do not compete on the basis of prices. Japanese companies were absolutely unable to compete with companies in South Korea, China and Taiwan based on prices. Japan responded by establishing a business model specializing in ONLY ONE market sectors where no other country can supply products. Japan uses this model to supply products with unparalleled Japanese technologies and quality to companies in other countries in the manufacturing and service sectors. But now this business model is facing severe challenges due to the plunge in global demand caused by COVID-19. Nevertheless, once the global economy starts to recover, the business climate for Japan is likely to improve rapidly as companies also benefit from a weaker yen as a risk-on environment returns.

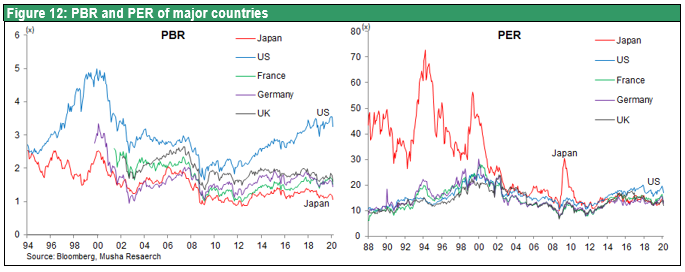

As shown in Figure 1, Japan ranks among the world’s most successful countries at controlling the spread of COVID-19. Japan may become the next country after China to return its economy to normal and perhaps even go ahead with the Olympics this summer. Despite having this advantage. Japan also has a problem because foreign investors have been selling off all their holdings in Japan. Foreign investors accounted for 70% of the TSE trading have been the buying-engine during the Abenomics rally that started in 2012. With a dividend yield of 3.1% and a PBR of 0.9, Japanese stocks are at a level that factors in a continuous loss of corporate value for many years into the future. These are the lowest valuations among the world’s major countries. This is clearly the margin of safety defined by Benjamin Graham, which means stocks will remain undervalued regardless of what happens.

The conclusion is that we may be near the point where investors worldwide are forced to rapidly increase their weightings of Japanese equities.