Aug 31, 2020

Strategy Bulletin Vol.260

Post-Abe will still be “Abe”

– The Abe administration’s historic achievements and the political situation today

(1) Prime Minister Abe’s historic achievements

From the standpoint of a front-line market observer for four decades, the achievements of the Abe administration are nothing short of remarkable. Decades from now, historians will probably view the Abe era as a trailblazing period that set the stage for a new phase of progress in Japan.

Three of the Abe administration’s many achievements deserve special mention. First is the reestablishment of a clear direction for Japanese diplomacy. Second is ending deflation and returning the Japanese economy to a growth trajectory. Third is a long list of reforms involving the government, corporate governance, working styles and other fields, although still more work is needed.

Prime Minister Abe defined Japan’s position in the age of US-China hostility

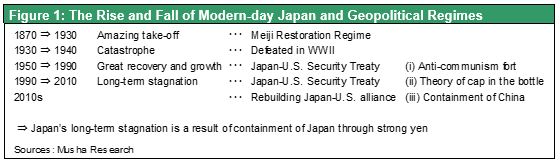

Since the Meiji Era, relations with superpowers that determined the world order have been the fundamental factor behind Japan’s periods of prosperity and difficulty. Prosperity during the Meiji and Taisho Eras were underpinned by an alliance with Britain. Defeat in World War II was linked to Japan’s decision to rise up against this alliance. Periods of economic growth and weakness in the postwar years were similarly influenced by superpower relationships. The Japan-US alliance during the cold war was behind Japan’s economic success that lasted from 1950 until the bursting of the asset bubble in 1990. This was followed by the “lost 20 years,” which was caused primarily by a shift in the national security framework after the cold war ended. The United States and Japan lost a common enemy when the Soviet Union collapsed. With this enemy gone, the United States began to view Japan’s extremely competitive industries as its greatest threat. The result was vigorous Japan bashing.

The Japan-US military alliance, with Japan in a subordinate role, became an instrument for containing Japan. The high-tech industry cluster that Japan had worked so hard to establish was destroyed. Some people refer to this as the national security “cap in the bottle” (containment of Japan’s military power) era. When the Abe administration began in 2013, the Japan-US military alliance acquired a new definition against the backdrop of the US-China confrontation. Looking ahead to a new era of US-China hostility, Japan started taking diplomatic actions based on an all-inclusive perspective of the world. Prime Minister Abe played the leading role in determining Japan’s position in this new world.

The big shift in the US view of Abe from a dangerous nationalist to a trusted friend

Immediately after the birth of the second Abe administration in 2013 and the prime minister’s visit to Yasukuni Shrine, journalists in Europe and North America were extremely critical of Prime Minister Abe as a nationalist. China, which had been adopting an increasingly resolute stance about the Senkaku Islands, started a campaign with the goal of isolating Japan by criticizing the Abe administration and Japan. China attempted to brand Abe as a nationalist who wanted to alter the postwar regime (a world order determined by the victors of WWII: US, Britain, Russia, China). Today, everyone agrees that China is dangerous. But Prime Minister Abe was first among leaders of the world’s major countries to point out this danger and he subsequently revised laws involving national security in order to reinforce the Japan-US alliance. This is one of the greatest accomplishments of the uncompromising Abe administration.

When he was a candidate, President Trump said that he would label China a currency manipulator and impose sanctions on his first day as president. Prime Minister’s close relationship with President Trump is due to more than their affinity for each other. A shared strategy is another key factor. The level of trust that Prime Minister Abe enjoyed within the G7 would have been inconceivable for a Japanese leader in the past. Yoshihisa Komori, a Sankei Shimbun correspondent in Washington, recalls that the US media were wary of Prime Minister Abe when his first administration started in 2006. The media labeled him a dangerous hawkish nationalist who clearly wanted Japan to be an “normal country” with respect to issues involving its constitution and history. In 2006, Mr. Komori predicted in a New York Times article that Mr. Abe would become a completely modern, frank and trustworthy friend of the United States, whether for Democrats or Republicans. Looking back now, this prediction was right on target. In the August 30 Sankei Shimbun, Mr. Komori stated that it was Mr. Abe’s own skill, hard work, beliefs and philosophy that changed US headwinds into a tailwind of an unprecedented magnitude.

The United States is obviously going to be the winner when the current period of hostile US-China relations comes to an end. When this happens, the world is very likely to see exactly how much the on-target strategies of Prime Minister Abe have strengthened the Japanese economy and the country’s global stature. Humanism is most likely behind Mr. Abe’s recognition of the danger of the totalitarianism of China and North Korea. He was the first Japanese politician to consistently work on bringing back Japanese citizens who were abducted by North Korea. Since becoming prime minister, Mr. Abe made these abductions one of the highest priorities of Japan-US diplomacy and asked President Trump to include this subject in his negotiations with North Korea.

A geopolitical perspective is important because geopolitics determine the foundation for the economy. At one time, Japan was the world leader in the high-tech sector. Since then, Japan has been overtaken by South Korea, China and Taiwan due to US actions to make Japan weaker. Subsequently, a dramatic favorable shift in Japan-US relations has given Japan a very advantageous position within the international division of labor. This position is certain to be an impetus for making Japan’s economy stronger.

(2) The leading deflation fighter but fiscal soundness was a problem

Why the prime minister started Abenomics

Prime Minister Abe is responsible for ending deflation as well as Japan’s “lost 20 years.” The geopolitical factors I have just discussed were one cause of Japan’s prolonged economic stagnation. But another reason is the mistake of implementing fiscal austerity policies. Between 2000 and 2012, Japan enacted austerity measures for destroying the asset bubble, limiting credit and holding down government spending. In 2003, I and a well-known journalist visited Prime Minister Koizumi with introduction by Mr. Abe, who was then Deputy Chief Cabinet Secretary. At that time, I advised that inflationary policies were needed to increase nominal economic growth. Prime Minister Koizumi, who was regarded at that time as a reformist, rebuffed me by saying that inflation must not be allowed to happen. At that time, no one was interested in talking about the need for aggressive macroeconomic initiatives. The reason was that academics, politicians and journalists had all been brainwashed by the fiscal reconstruction campaign of the Ministry of Finance. This atmosphere became even stronger while the Democratic Party of Japan was in power. Since about 2000, Japan struggled with the “Japan disease” of persistent deflation accompanied by abnormally low interest rates that were also the lowest in the world. These problems were signs of inadequate demand and surplus savings. Policies allowing continuous deflation caused the yen’s appreciation to accelerate, which almost eliminated the competitive edge of Japanese industries in global markets (and destroyed Japan’s core high-tech industries).

Without Abe’s policies, deflation would still be alive

When the Abe administration started in 2013, the prime minister enacted the first-ever fundamental shift in the composition of measures to fight deflation. The majority of academics, economists and journalists opposed this move. Mr. Abe named Koichi Hamada as a cabinet adviser and named Haruhiko Kuroda, who was head of the Asia Development Bank, governor of the Bank of Japan. Mr. Kuroda was one of very few high-ranking government official who had criticized policies for allowing continuous deflation. The result was the start of the three arrows of Abenomics: large-scale monetary easing, fiscal stimulus through government spending and structural reforms. During the second half of his administration, economic growth and stock prices lost momentum as, contrary to Mr. Abe’s wishes, a counteroffensive by supporters of deflation resulted in two consumption tax hikes and a return to the policy of aiming for a primary budget surplus. Nevertheless, Mr. Abe’s ability to accomplish on his own an enormous shift in economic policies is very surprising. Since 2009, Musha Research has consistently been strongly urging the Japanese government to take aggressive macroeconomic actions along with monetary measures for preventing the yen from appreciating. During that time, there was a strong feeling that I was fighting this war by myself.

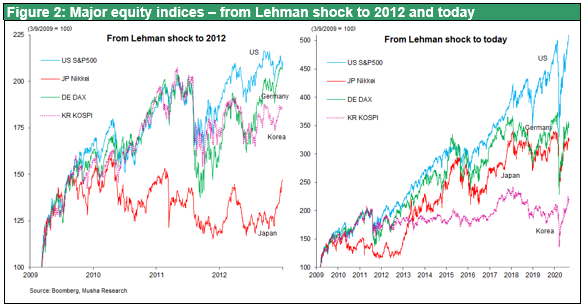

Japan’s economy began to improve significantly in 2013 as stock prices rose, the number of jobs grew and the nominal GDP increased steadily. Some observers believe that the economy would have improved even without Abenomics because this upturn was merely part of a cyclical phase of global economic expansion. But this is a mistake. As Figure 2 shows, between 2009 and 2012, stock prices in Japan remained at the record lows of the global financial crisis while US and European stock prices almost doubled from their lowest points during this crisis. The primary cause was the strong yen-deflation policies of the DPJ administration and Bank of Japan under Governor Masaaki Shirakawa. For example, immediately after the devastating March 2011 earthquake and tsunami, the G7 countries jointly intervened to halt the yen’s post-quake rise. Although this created an ideal environment for correcting the yen’s value, Japan did not take advantage of this opportunity.

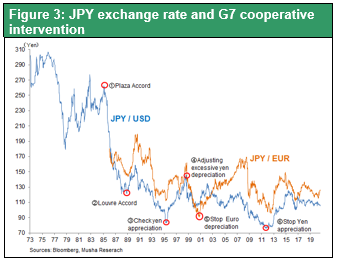

Figure 3 shows the exchange rate of the yen and joint G7 interventions. Five of the six joint interventions resulted in a big reversal in the direction of foreign exchange rates. But the intervention in March 2011 failed to reverse the direction of foreign exchange rates and the yen continued to appreciate for two more years. This was because the Bank of Japan did nothing at all while the Fed and European Central Bank stepped up the pace of reflationary measures using quantitative easing, which dramatically increased the size of their balance sheets. As a result, the already excessively strong yen appreciated even more in 2011 and 2012. This was the final blow to the ability of Japan’s high-tech companies to compete in global markets. For instance, Elpida Memory filed for bankruptcy and the LCD and television businesses of Sharp, Panasonic and Sony were no longer competitive.

Prime Minister Abe’s great accomplishment was the eradication of this deflationary mindset that had destroyed the animal spirits of Japanese businesspeople and investors. During the seven and a half years of the Abe administration, deflation came to an end, although the 2% inflation target was not achieved, stock prices surged 124%, and there was an immense upturn in jobs. In fact, Japan’s unemployment rate in June was only 2.8% despite the COVID-19 crisis.

Regrets that measures for financial soundness stopped economic growth

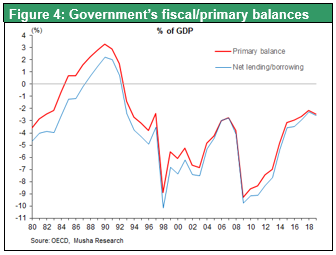

Japan’s economic growth rate declined during the second half of the Abe administration. Two consumption tax hikes and a resumption of measures to improve fiscal soundness (the primary budget balance) exerted enormous downward pressure on the economy. Japan’s primary budget deficit decreased from -9% in 2013 when Abenomics started to -2% in 2019. This improvement of 7 percentage points means that the public sector was taking away demand equivalent to 1% of the GDP every year. In other words, the second arrow of Abenomics, government spending, was having a huge negative impact on the economy. The consumption tax hikes were based on an agreement among the LDP, Democratic Party of Japan and Komeito and were not what Mr. Abe himself wanted. Mr. Abe probably regrets more than anything else the negative impact these two tax hikes had on the economy.

The Abe administration has been making steady progress with structural reforms, the third arrow of Abenomics. The prime minister demonstrated his leadership in many areas: (1) working style reforms, more women in the workplace, free education; (2) revisions to Japan’s vertical government administrative structure, creation of the Cabinet Personnel Bureau, role of the Office of the Prime Minister, supervision of the cabinet; (3) corporate governance reforms, Government Pension Investment Fund, postal savings reforms; (4) corporate income tax reduction; (5) Trans-Pacific Partnership membership; and other initiatives.

(3) The post-Abe era will still be “Abe”

The prime minister’s stature and cohesive power will increase; he is certain to come back

Mr. Abe, who is a politician with an unprecedented record of accomplishments, will remain a member of the Diet. Following his resignation, there will be a decrease in media criticism of Mr. Abe simply for the sake of criticism. As people become aware of his accomplishments and success of his policies, Mr. Abe’s reputation is likely to improve greatly.

If Mr. Abe’s health problem can be cured, there could be a third Abe administration. If concerns about his health remain, Mr. Abe would probably instead become a senior adviser or deputy prime minister. In these roles, he would be a kingmaker. Age 65 is too early to retire. This is why Mr. Abe will still define the post-Abe era. Consequently, the next prime minister should be someone who can continue the policies of the Abe administration and be an intermediary for the return of Mr. Abe. Calls for Mr. Abe to return will become even stronger if President Trump wins a second term. Ultimately, Mr. Abe may acquire similar stature as that of Franklin Roosevelt, who was elected president four times.

Markets will respond favorably to a continuation of Abe politics

LDP Secretary-General Toshihiro Nikai holds the key to the selection of the next prime minister, who is to be chosen by LDP members of the Japanese Diet. As a supporter of a fourth term for Prime Minister Abe, Mr. Nikai is very likely to ask Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga to serve briefly as a stopgap prime minister.

There are three main expectations for the next administration: (1) government actions regarding COVID-19; (2) reflationary measures and reforms; and (3) more advances with the use of digital technologies. Mr. Suga performed the role of a cheerleader for a variety of reforms, making him the best choice for overseeing initiatives involving reforms and digital technologies. But this will be a provisional administration. As a result, there will probably be no activities for long-term issues like amending the constitution. This lack of action will probably please foreign investors. If so, investors can expect to see stock prices move up when the new prime minister takes office.