Feb 07, 2022

Strategy Bulletin Vol.298

The deeper meaning of the ongoing reduction of the wage gap

-Fiscal policy and inflation as a channel for inter-sectoral income redistribution

The digital revolution has led to a widening gap

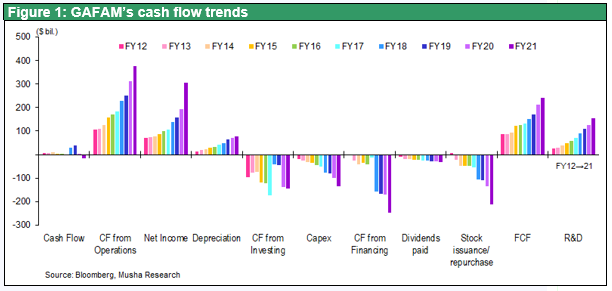

The digital revolution has led to a widening of the gap, known as the digital divide. While higher-skilled workers enjoy higher wages because they are more productive, lower-skilled workers are less productive and their wages rise more slowly. In addition, today's leading companies, such as GAFAM and other internet platform companies, do not hire people and do not invest in fixed assets even though they are growing. This was not the case with the former leading companies such as GM and GE. As they grew, they made large capital investments, expanded their factories, and increased employment significantly. The resulting middle class has been the engine of American democracy.

But instead of investing and employing more people, GAFAM has been returning profits to shareholders in the form of dividends and share buy-backs. This raises stock prices, further enriches the rich and widens inequality. Thus, the fear that the digital revolution will make people unhappy has been voiced.

The Corona pandemic has led to higher wage increase in low-skilled sectors

However, a different phenomenon is now occurring under the Corona pandemic: the narrowing of the gap. Low-skilled job wages, which had been neglected until now, are growing rapidly. Wages have risen faster for frontline workers than for managers, for part-timers than for full-time workers, for women than for men, for low-skilled than for high-skilled workers, and for young than for middle-aged workers since 2021.

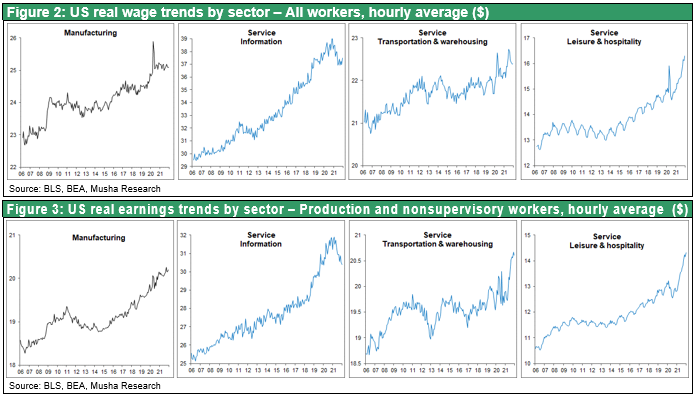

When we look at real wages by sector, we see that, overall, neither manufacturing nor services have yet entered a wage growth trend. However, when looking at the sub-sectors, wages have risen rapidly only in the transport and warehousing and entertainment sectors. Within these sectors, the salaries of non-managerial workers, such as truck drivers and waiters and waitresses in restaurants, have risen sharply.

On the other hand, real wages in the information industry, which has seen the highest growth in productivity, and which used to represent high-wage, high-skill work, have fallen sharply since the outbreak of the Corona disaster. In the office sector, where productivity has been boosted by the digital revolution and remote working, the number of job vacancies has not increased significantly, labor supply and demand has been sluggish, and wage growth has not kept pace with prices. The long-anticipated narrowing of the wage gap has been realized in the unusual circumstances of the Corona pandemic.

Fiscal support for wage growth in low-skilled work

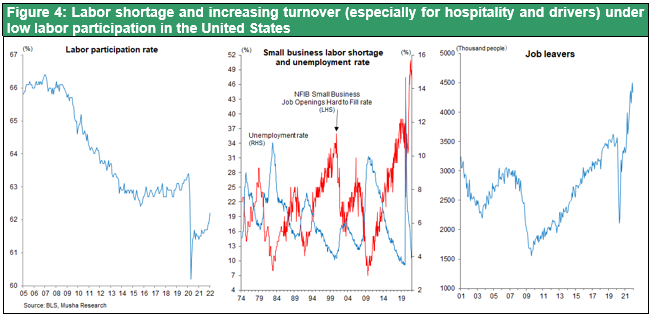

It could be argued that workers have greater choice and are beginning to choose jobs based on pay and working conditions. Workers are no longer attracted to sectors that are harsh, unappreciated, and poorly paid. The job opening rate is at an all-time high, especially among small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which tend to employ relatively low-skilled workers, and the difficulties to fill job vacancies is at an unprecedented level The number of people leaving their jobs in the US is at an all-time high, not just a pre-Corona level. These current phenomena represent increased bargaining power of workers.

Behind the scenes, this narrowing of the wage gap has been supported by massive fiscal stimulus and monetary easing. The ultra-aggressive fiscal and monetary policies under the Corona pandemic created demand in the harsh, low wage labor sectors where productivity did not rise, putting pressure on labor supply and demand. Without the support of fiscal and monetary policy, there would have been job cuts in low-skilled sectors such as transport and leisure, where productivity growth is low and employment buffers are scarce, and inequality would have widened further.

Will the gap continue to narrow? The key lies in the continuity of fiscal and monetary support

What will happen to this trend of narrowing the wage gap in the future? Some believe that the tightness in labor supply and demand in the low-skilled sector is temporary and will eventually dissipate. In terms of the labor participation rate, it has fallen from 63% before Corona to 60%, and although it has recovered, it is still in the 62% range. It is true that a large number of people have not returned to the labor market, but we can assume that this is largely due to transitory factors, such as (1) the need to care for people and children who are out of school due to the Corona pandemic, and (2) the increase in income from government subsidies, which has temporarily eliminated the need to work. Once the coronary pandemic is over, these factors will become new labor supply factors, easing the tight supply-demand balance in the low-skilled, low-paid labor sector. It is also possible that a pause in fiscal stimulus and a reduction in policy support, such as monetary tightening, will restrain aggregate demand and depress labor demand.

In the longer term, however, labor supply and demand will continue to be loose in high-skill sectors and tight in low-skill sectors. The Corona pandemic has reminded us of the magnitude of the productivity gains that can be made through the digital revolution and remote working. It is likely that job opportunities in such areas will not be as high as before and that wages will continue to be difficult to increase.

On the other hand, whether the shortage of labor will continue in low-skilled areas where productivity is not high enough? Once the Corona pandemic is fully over and the labor force participation rate fully recovers as people who have temporarily retired from the labor market return to the market, the shortage may be resolved, and wage growth may subside. Thus, for truck drivers and the hospitality industry to continue to be in short supply, aggregate demand must be strong. For this to happen, fiscal and monetary policy support would be essential.

The narrowing of the wage gap can be seen as a positive aspect of Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen's theory of a high-pressure economy, in which demand exceeds supply. If demand increases equally across sectors, wage growth will be lower in sectors with high productivity growth and higher in sectors with low productivity growth. This would lead to a disparity in the rate of price growth between sectors and would alter the distribution of income between sectors.

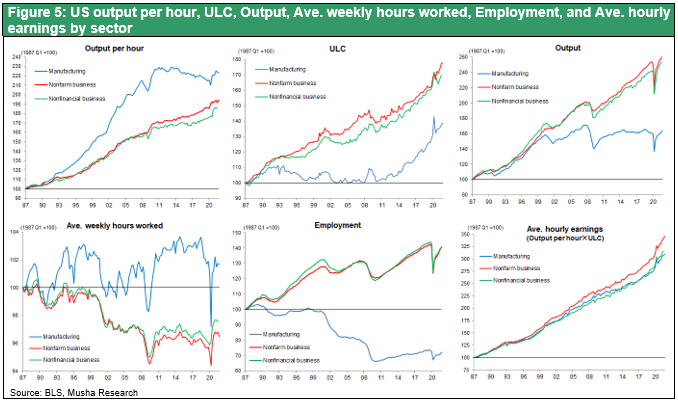

Figure 5 shows the changes in productivity, unit labor costs, output, employment, and wages between sectors in the US since the 1980s, showing how the difference in the rate of wage growth and inflation between sectors has led to a redistribution of income between sectors and promoted economic growth.

Since 1980, employment in the manufacturing sector, with its high productivity growth, has fallen and manufacturing output has stagnated, but demand from the non-manufacturing sector, with its low productivity growth, has grown and this has driven economic expansion. In the non-manufacturing sector, productivity growth was low, wages continued to rise faster than productivity growth, and unit labor costs rose sharply, but the aggregate demand generated by this sector drove economic expansion. In other words, the fruits of higher productivity in the manufacturing sector were transferred to the non-manufacturing sector through the inflation gap, and this generated additional demand.

The same is now happening between the high-skill information sector and the low-skill services sector. Put simply, the fruits of the productivity gains brought about by GAFAM are being translated into higher wages for low-skilled workers as the wage growth gap is closed, and new demand is being created there.

In this way, the narrowing of the gap that is now taking place in the US market can be seen as a trend towards optimizing the allocation of labor under the new working environment.

Implications for monetary policy, interest rate hikes should be gradual and cautious

The end of the Fed's ultra-easy monetary policy, the start of the taper and the start of interest rate hikes, which the Fed hurriedly announced at the end of last year, is disturbing the market. The market, which had been comfortable with two or three rate hikes in 2022, suddenly revised its outlook to five or six hikes, causing short- and long-term interest rates to rise and stock prices to plummet. There is also a hawkish view emerging that the Fed has misread rapid price increases and needs to brake hard.

But as we have seen, wage growth has been localized and the fact that the wage gap by occupation has narrowed suggests that conditions are not as they were in the 1970s, when a general tightening of labor supply and demand led to a spiral of wages and inflation. Takatoshi Ito, a professor at Columbia University, has said that "we will raise interest rates two or three times in the first half of the year and then wait and see" (Nikkei Shimbun, February 3), which seems a reasonable view.

We believe that Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, who are in charge of the U.S. economy, deeply understand the importance of the growth cycle, in which inflation of around 2% leads to income redistribution among sectors and economic growth.