Dec 01, 2022

Strategy Bulletin Vol.319

Global growth driven by a strong dollar, embarking on the dollar empire cycle

World locomotive, from China to the U.S.

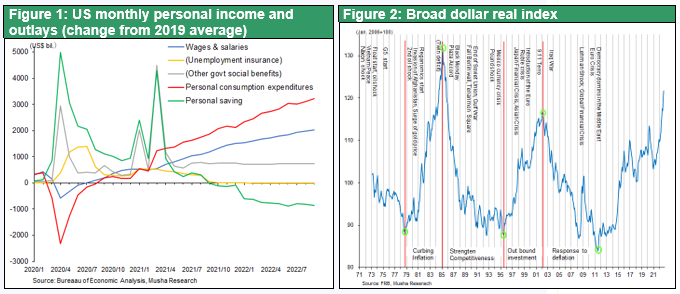

The year 2022 seemed like a natural year for a great economic difficulty. The following three factors were considered to be the main causes of the global recession: (1) the fastest monetary tightening in history, 400bp from 0 to 4% in the U.S., (2) the rapid slowdown of the Chinese economy due to the corona pandemic lockdown and bursting of the real estate bubble (real GDP from 8.1% in 2021 to 3.0% from January to September 2022), (3) the soaring energy prices and economic difficulties in Europe due to the war in Ukraine. Given the magnitude of the problems in the global triad, it was natural that the global economy would be in a serious economic recession in 2022, but this did not happen. The expected problems, such as the U.S.-China trade war and decoupling (China's exclusion from the global supply chain), and the emerging economies' difficulties as the strong dollar forced capital outflows, did not become more serious.

The reason why the global economy did not lose its vitality in 2022 can be summed up as "the huge stomach of the U.S. consumer was alive and well. Musha Research has been saying for a year, "The era of the strong dollar may have begun. The period in which the U.S. supplied the world with dollars in response to the Corona crisis and the dollar weakened as a result is over. From now on, the dollar will become stronger, the world's capital will gather in the U.S., and we will enter an era in which U.S. domestic demand, or exports to the U.S., will propel each country's economy. China's economic decline may be even greater. On the other hand, U.S. consumption is strong, and the locomotive of the global economy is shifting from China to the United States." (Strategy Bulletin No. 292, "The Strong Dollar and Weak Yen Will Boost Japan's Price Competitiveness and Boost Corporate Profits," October 19, 2021), and this is exactly what we are seeing now.

The mechanism by which a strong dollar maximizes U.S. (≒world) demand

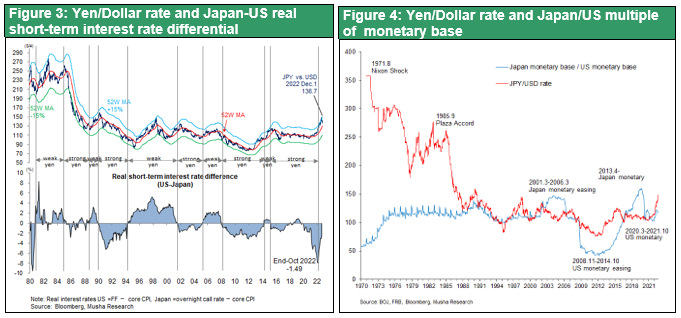

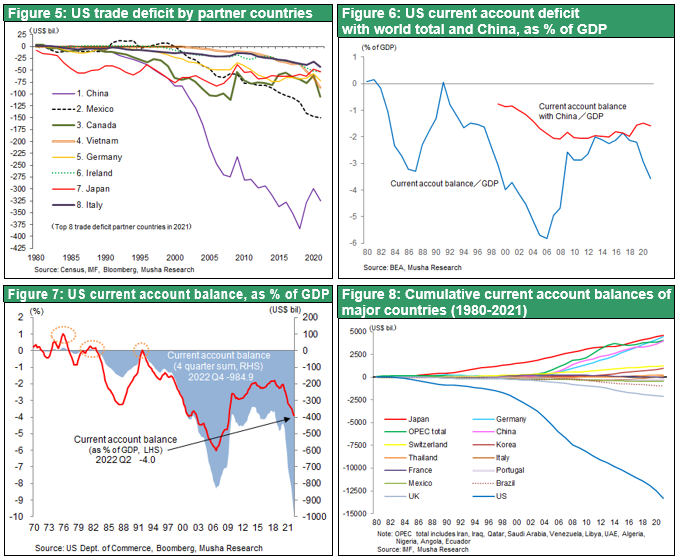

The key lies in the unexpected appreciation of the dollar. The dollar has appreciated in ways that cannot be explained by exchange rate theory. (1) The dollar appreciated against the backdrop of rising inflation (= depreciation of currency value). (2) Despite the sharp rise in U.S. interest rates, the core CPI is running as high as 6%, and the yield on the 10-year nominal Treasury note is less than 4%, meaning that the real interest rate is significantly negative at more than 2%. (3) The dollar also appreciated amid a sharp increase in the U.S. current account deficit to $1 trillion (4% of GDP). For those who have been using exchange rate models to forecast currencies, this sharp rise in the dollar could not be explained (see Figure 3, 4).

The inflow of funds to the U.S. due to the strong dollar pushed down U.S. long-term interest rates, lowered U.S. import inflation, boosted real purchasing power, and gave many emerging economies and resource-rich countries an engine for increased exports to the U.S.

In terms of causality, it can be said that the inflow of U.S. funds drove global growth by driving the U.S. IS imbalance (excess consumption far exceeding saving).

As seen in Figure 5, the U.S. external deficit has increased significantly vis-à-vis Mexico, Vietnam, Canada, Ireland, and other countries, while it has begun to decline vis-à-vis China, and the U.S. current account deficit has reached 4% of GDP on a $1 trillion annual basis. Figure 6 shows the U.S. current account deficit as % of GDP is increasing rapidly while the deficit with China contracting substantially. It can be seen that export bases other than China to the U.S. have grown significantly under the U.S.-China confrontation.

The strong dollar is directly related to the U.S. national interest at present

The U.S. dollar's appreciation is directly related to the U.S. national interest at the present time:

- A decline in import prices suppress inflation and push up real income. The U.S. imports $2.8 trillion (¥364 trillion) of goods annually. A 10% appreciation of the dollar over the previous year would have the effect of lowering import prices by $280 billion. Since annual consumption in the U.S. is $17 trillion, assuming that all of this is reflected in consumption prices, the effect would be to push down consumer prices by a maximum of 1.3% (i.e., push up real purchasing power).

- In addition, the inflow of funds from abroad will suppress U.S. long-term interest rates and stimulate demand.

- Furthermore, a strong dollar will increase the U.S. foreign investment power, boost the U.S. presence in the world, and lower the position of Russia and China, which are competitors.

A strong dollar is also good for the global economy. It is a means of stimulating U.S. consumption and providing additional demand to a world that is suffering short of demand.

The Dollar's imperial cycle begins to take shape

Thus, the strong dollar has begun to trigger a virtuous cycle of increased U.S. imports (= increased U.S. debt), accelerated global growth, and the concentration of capital in the United States. As long as the dollar remains strong (or the dollar exchange rate remains stable at a high level), this virtuous cycle will sustain U.S.-centered global economic prosperity. The author analyzed this in Chapter 4, "The Establishment of the Global Imperial Circle and the Dollar System," in "New Imperialism," 2007 Toyo Keizai. “The circulation of income and capital, the mechanisms that make it sustainable, is essential to the long-term prosperity of an economy. The Pax Britannica and Pax Americana I periods (1950s-1970s) formed the patterns of capital flows that supported their respective prosperity, but after the period of turmoil that followed the Pax Americana I period, a new stable capital flow, the global imperial flow, began to emerge at the end of the 1990s. “I assume that the global imperial cycle is now an extension of the Pax Americana.

Blind spot for the strong U.S dollar #1 => Decline of US. Competitiveness

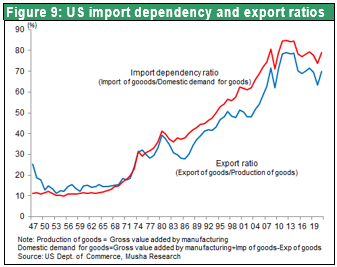

Although the dollar's appreciation is a good thing, there are two blind spots. The first is a decline in the price competitiveness of U.S. companies. When this becomes apparent, the strong dollar will be put on the brakes, but at present, U.S. companies compete with other countries on price only in a very small number of items, such as automobiles. Most U.S. manufacturers are engaged in products with technologies and non-price competitive advantages that are not manufactured in other countries, and there is little fear that their competitiveness will decline even if the dollar appreciates. As shown in Figure 9, the U.S. dependence on imports for U.S. domestic demand for goods has risen to 80% from around 10% in the early 1970s, and there are almost no U.S. manufacturing firms in the U.S. for most products.

In the absence of overseas competitors such as Big Tech GAFAM, the increase in local costs due to the strong dollar can be met by raising local sales prices, in which case U.S. foreign income (= income in dollar terms) will remain unchanged.

Blind spot for the strong U.S dollar #2 => The spiraling increase in interest payments

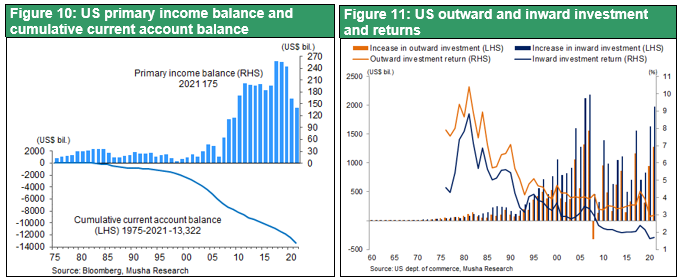

The second blind spot is the increase in interest and dividend payments due to the cumulative increase in U.S. debt. Since the U.S. external deficit has reached more than $13 trillion in the past 40 years cumulatively, if interest at the current long-term interest rate of 4% were to accrue, the annual external payment would be $533 billion (negative primary income), and the country should be stuck in a hellhole of spiraling debt growth, but this has not happened. The U.S., a country with huge net external debt, still has a primary income surplus of $175 billion, including interest payments. The U.S. is the only country in the world that pays no cost for its debt. This is probably due to the fact that the U.S. is a reserve currency-issuing country, so seigniorage works, U.S. companies' overseas profitability is high, and overseas companies' profitability in the U.S. is low (Figure 11). As a result of these factors, the U.S. has been able to increase its external debt (i.e., dollar issuance) and drive global economic growth. This strength of the U.S. in issuing dollars is the secret weapon of the U.S. hegemony. The U.S. is sure to make the most of this privilege in the struggle for supremacy between the U.S. and China, which is a top priority for the U.S.

An Unexpected Strong U.S Era with a Strong U.S. Dollar (as envisioned by the author)

This new frontier that the dollar has reached is something that has never been envisioned by previous exchange rate debates and is new territory that has not been explored by either market participants or academics. Many commentators have presented thought-leading analyses of the dollar and the yen in that era, and have shown new insights to market participants. Paul Krugman (Sustainability and the Decline of the Dollar 1985), who argued that a strong dollar is not sustainable under massive external debt; Richard Koo who insisted that the currency market would react with unbounded yen appreciation unless import barriers of Japan were removed("The Good Yen's Appreciation and the Bad Yen's Appreciation," 1994);Mototada Yoshikawa ("Money Defeat," 1998), and Akio Mikuni ("The Exile of Surplus," 2005), who criticized the Japanese economy for accumulating trade surpluses and hoarding dollars that were to become scrap paper due to accumulated debt, are historic analyses of this kind. However, we are now entering a new era of strong dollar stability of a completely different dimension.