Feb 10, 2011

Strategy Bulletin Vol.39

The United States, Germany and Japan are remarkable beneficiaries of globalization this year

Money is shifting quickly from bonds to stocks and from emerging countries to industrialized countries

A massive movement of funds has been taking place since the start of 2011 as investors restructure their portfolios. Money is flowing from emerging country stocks to U.S. equity funds as prices of bonds and gold fall. This is a dramatic change from the situation that existed until the fall of 2010 as investors constantly bought bonds due to expectations for global deflation. Driving this shift is the polarization of views about risk involving the global economy. Excessive risk-taking is occurring in emerging countries. In contrast, there is excessive risk aversion in industrialized countries. In China, people are beginning to become worried about the sustainability of economic growth because of increasing inflation and a growing asset bubble. Signs of a bottleneck in economic growth are appearing in the majority of emerging countries as they adopt tighter monetary policies in response to overheated economies, inflation and asset bubbles. In industrialized countries, particularly key countries like the United States, Germany and Japan, the economic downturn has ended as companies have streamlined operations, household savings climb and prices of assets fall. Furthermore, all three countries have ultra-loose monetary policies because of stagnant demand and employment. QE2, the new monetary easing initiative in the United States, will create more difficulties for economies in emerging countries by increasing inflows of capital to these countries, causing their currencies to appreciate and governments to enact tighter monetary policies in response. In 2011, industrialized countries that have finished their economic corrections, especially the United States, Germany and Japan, will be the center of attention. The resulting upswing in prices of stocks and assets in industrialized countries will probably create new demand.

A revision in how globalization is viewed

These developments require making a revision in the widely accepted perception of globalization. Globalization, which equates to the international division of labor, is normally equated to rapid growth in emerging countries and stagnation in industrialized countries. Instead, globalization should be viewed as a process that contributes to the growth of both emerging and industrialized countries. Under the international division of labor, emerging countries supply cheap labor. But this alone is not enough to support economic vitality. Industrialized countries supply technologies, capital, management know-how and marketing. All are vital to economic growth. This explains why industrialized countries should benefit from globalization just as much as emerging countries do. Rising wages are rapidly improving the standard of living in emerging countries. In industrialized countries, globalization is enabling companies to increase earnings. After earnings plunged following the Lehman shock, U.S. corporate earnings have rebounded to an all-time high. At the same time, Japanese companies have staged a powerful recovery in earnings even as the yen appreciated sharply. Both of these recoveries represent the benefits of globalization.

Strong earnings and rising stock prices are the starting points of a virtuous economic cycle in industrialized countries

How should industrialized countries transform the benefits of globalization into the greatest possible amount of demand? There are many potential methods. Examples include (1) the wealth effect from rising stock prices, (2) knowledge-intensive investments in industrialized countries, (3) high salaries for people with the highest levels of knowledge in the world, and (4) a higher standard of living in industrialized countries and the associated service industries needed to support that standard of living. All are challenges that industrialized countries must tackle. But one point is obvious. The engine for economic growth in industrialized countries is higher corporate earnings and the resulting upturn in stock prices.

The new phase of globalization that is driven by industrialized countries

A look back at progress in globalization reveals that this process has gone through a number of clearly defined phases. The first phase was characterized by explosive growth in U.S. demand and the take-off of the Chinese economy (2000 to 2007). Capital flowed to industrialized countries, and particularly the United States, and interest rates were low. An asset bubble emerged as this climate pushed up asset prices. The Chinese economy took off as exports to the United States skyrocketed. During the second phase, the bubble burst and demand in emerging countries surged (2007 to 2010). The end of the U.S. asset bubble caused a sharp contraction in global demand. In response, China increased public-sector expenditures and the United States adopted an ultra-easy-money policy. Investors responded by channeling their capital to emerging countries. Economic growth accelerated in these countries as a result, producing asset bubbles and inflation. Today, I believe we are on the verge of the third phase (starting in 2011). During this phase, economic growth will start to return to the industrialized countries. Directing the benefits of globalization to industrialized countries will most likely spark a new cycle for the creation of demand. Thus we have been benefiting from the powerful follow-wind of globalization for many years even historical financial occurs. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- For reference Strategy Bulletin vol.12 (Apr.27.2010) The revival of the U.S., German and Japanese economies -Germany is gaining a competitive advantage as the crisis in Greece unfolds -

“Holding down unit labor costs” is becoming the key to economic vitality

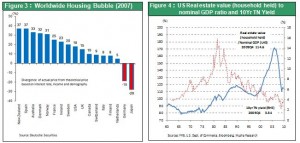

During the first four months of 2010, we have seen an almost consistent rally in stock prices in industrialized countries and a decline in emerging countries. This reality is precisely the opposite of the consensus outlook for economic growth in emerging countries and stagnation in industrialized countries. Significantly, stock prices have been very strong in three unpopular countries: the United States, Germany and Japan. Japan has been widely viewed as an Asian country in decline due to the lack of economic growth over the past decade. But in 2010, Japan has recorded the best performance in Asia. In Europe, one of the best performers is Germany, a country that had been the region’s most stagnant economy because of its high wages. The reviving economies of the United States, Germany and Japan share a common characteristic: all three are “holding down unit labor costs” by boosting productivity while tightly controlling costs. I have discussed the U.S. and Japanese economies in previous reports*. In this report, I will focus on how Germany is making progress in lowering unit labor costs. This subject has a bearing on stock market performance and is also one cause of the current crisis in Greece. *I have explained that U.S. labor productivity increased because of workforce reductions that could even be regarded as excessive (unemployment rose by almost 4 percentage points in 2009 far exceeding 2.4% GDP decline ). The result was a sharp decline in labor’s share of income (See Key Strategy Issue Vol. 289 and other reports). I have also explained that Japan achieved the world’s only significant decline in unit labor costs as the yen appreciated over a period of more than 20 years (See Key Strategy Issue Vol. 287 and 288).

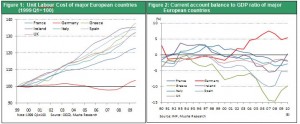

Dealing with unbalanced economic growth is a constant problem with currency unification

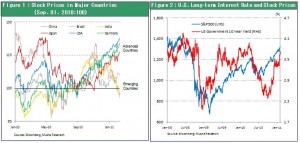

The worst of the Greek debt crisis seems to be behind us because of financial aid from the IMF and a number of countries. However, this aid package does not eliminate the fundamental cause of this crisis. As a result, the world may have to deal with a much larger economic crisis during a future downturn in the global economy. The crisis in Greece, along with other problems the EU faces, are all linked to uneven economic growth among EU countries (differences in costs and the rate of improvement in productivity). Without currency unification, economic stability of individual countries would be preserved through changes in exchange rates of national currencies that offset these differences. But a single currency makes it impossible to rely on exchange rates. This explains why EU countries with low productivity are having such difficulty in taking the actions they require. Greece, which is the economically weakest EU member, has emerged as the first victim of the unified currency system. Soon after EU currency unification in 1999, there was an outflow of jobs from Germany, which had high wages at that time. Taking away these jobs were Ireland, Spain and new EU members with emerging economies, chiefly countries in Eastern Europe. The outflow of jobs created intense deflationary forces that pressured Germany to raise productivity and cut wages. On the other hand, costs rose sharply in EU countries that were capturing jobs from Germany because of severe labor shortages (Figure 1). Higher costs in other EU countries made Germany’s exports more competitive. Germany was soon reporting large current account surpluses while other countries had consistently large deficits (Figure 2).  The fixed exchange rate within the EU imposed by a single currency has the effect of increasing Germany’s competitive advantage, year after year. I believe there are four ways to resolve this problem within the eurozone. First is to improve the productivity of weaker EU members . Second is to lower wages and prices (deflation) in these weaker EU members . The third is to raise wages and prices (inflation) in Germany. And finally, if none of these three measures are possible, the fourth option is to terminate currency unification in Europe. However, it would be impossible for the European Central Bank (ECB) to simultaneously execute policies with differing results ? wage inflation in Germany and wage deflation in weaker EU members . Furthermore, the role of the ECB differs from that of the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank, which is responsible for supporting employment and economic growth. The sole mission of the ECB is preserving the value of the euro. Fulfilling this role makes it almost impossible for the ECB to enact policies to produce deflation in emerging economies (option 2) or inflation in Germany (option 3). Due to these limitations, I believe that the only option for the EU and ECB is to enact emergency stopgap measures while waiting for the productivity of weaker EU members to improve (option 1). But if there is a steep decline in the global economy, the fourth option of considering the termination of currency unification looms larger. But taking this step would be very difficult from a political standpoint. For these reasons, I think there is still more potential for higher wages and corporate profit margins in Germany for the time being. Passing through the powerful winds of globalization and an unprecedented financial crisis, the global economy has returned to its most critical value metric: the unit cost of labor. Japan and Germany are the leaders in this respect. Furthermore, the prices of assets are far below their true values in both countries, despite the recent worldwide bubble in housing prices (Table 3). In addition, the United States is rapidly unwinding its housing bubble. This is why I believe that Japan, Germany and the United States will present attractive opportunities to investors.

The fixed exchange rate within the EU imposed by a single currency has the effect of increasing Germany’s competitive advantage, year after year. I believe there are four ways to resolve this problem within the eurozone. First is to improve the productivity of weaker EU members . Second is to lower wages and prices (deflation) in these weaker EU members . The third is to raise wages and prices (inflation) in Germany. And finally, if none of these three measures are possible, the fourth option is to terminate currency unification in Europe. However, it would be impossible for the European Central Bank (ECB) to simultaneously execute policies with differing results ? wage inflation in Germany and wage deflation in weaker EU members . Furthermore, the role of the ECB differs from that of the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank, which is responsible for supporting employment and economic growth. The sole mission of the ECB is preserving the value of the euro. Fulfilling this role makes it almost impossible for the ECB to enact policies to produce deflation in emerging economies (option 2) or inflation in Germany (option 3). Due to these limitations, I believe that the only option for the EU and ECB is to enact emergency stopgap measures while waiting for the productivity of weaker EU members to improve (option 1). But if there is a steep decline in the global economy, the fourth option of considering the termination of currency unification looms larger. But taking this step would be very difficult from a political standpoint. For these reasons, I think there is still more potential for higher wages and corporate profit margins in Germany for the time being. Passing through the powerful winds of globalization and an unprecedented financial crisis, the global economy has returned to its most critical value metric: the unit cost of labor. Japan and Germany are the leaders in this respect. Furthermore, the prices of assets are far below their true values in both countries, despite the recent worldwide bubble in housing prices (Table 3). In addition, the United States is rapidly unwinding its housing bubble. This is why I believe that Japan, Germany and the United States will present attractive opportunities to investors.