1) The worst of the euro crisis will soon be over

On September 6, the Governing Council of the European Central Bank (ECB) approved unlimited purchases of the bonds of countries in southern Europe. This is referred to as Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) and also called “SM2” (Super Mario 2 after ECB President Mario Draghi). A country must first ask the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) for assistance and meet other requirements. Nevertheless, this move is expected to bring about a fundamental shift in market sentiment, which had been consistently ruled by fear. This was the underlying cause of the euro crisis. The reversal in sentiment will occur because “the possibility of a collapse of the financial system due to growing fear” has been eliminated. A similar reversal from a market paralyzed by fear occurred after the $700 billion TARP (Troubled Asset Relief Program) was established in November 2008 and quantitative easing greatly increased the Fed’s balance sheet. The euro crisis that began in 2010 effectively stopped financial markets from functionin. Fundamentals linked to the north-south imbalance in Europe and reckless economies in southern European countries (low productivity and government deficits) were not the only cause. Markets also stopped functioning because of speculators who decided that a collapse of the euro was inevitable. This situation resembles the sell-off of mortgage-backed securities, corporate bonds and stocks to unreasonably low levels as the subprime loan crisis led to the demise of Lehman Brothers.

A market ruled by irrational fear is what caused the euro crisis. The scenario of not only Greece but also Spain and Italy becoming insolvent and abandoning the euro was unrealistic. Spain’s financial balance is excellent. The United States, United Kingdom and Japan are far worse off financially than Spain, but long-term interest rates in these countries are at historic lows. Nevertheless, Spain’s long-term interest rate has surged. In July, the gap between two-year government notes in Spain and Germany widened to the point where Spain was 6% and Germany had a negative return. Investors are factoring in a Spanish default within two years. Why? Unlike in the United States, United Kingdom and Japan, Spain, Italy and other eurozone countries do not have a central bank that can print money to underwrite deficits. As a result, the ECB has stated that it will assume this responsibility and speculators must abandon the scenario of panic.

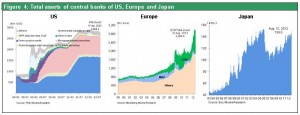

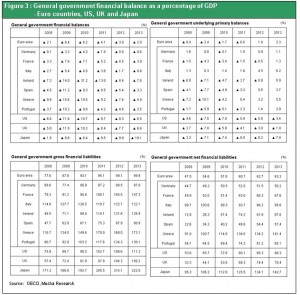

A 2012 OECD comparison of financial data reveals the points. First, government deficits as a percentage of GDP are 1.7% in Italy and 5.4% in Spain, far lower than 8.8% in the US, 7.7% in the UK and 9.9% in Japan. Second, the primary balance as a percentage of GDP is +4.5% in Italy (highest in the world) and +0.5% in Spain but -5.0% in the US, -3.0% in the UK and -8.2% in Japan, an enormous difference. Third, Spain’s net debt is 54.4% of its GDP, the lowest among major countries. This figure rises to 96.2% in Italy, 85.3% in the US, 74.4% in the UK and 134.1% in Japan, showing that Italy is in a much better financial position than Japan.

Preserving the euro is in the national interest of Germany. That means Germany must protect the euro at any cost. The country has the world’s second-largest current account surplus and an enormous external capital surplus because of investments from southern European countries. In the past, outflows of funds through Germany’s private-sector banks supported the circulation of external excess. But these outflows have stopped. Now the sole source of outflows of funds is the growing external account (external loans by the Deutsche Bundesbank to the ECB and other borrowers and other outflows) of the central bank. If the euro collapses, these loans would become massive non-performing assets. Consequently, cutting off financing to southern European countries is already no longer an option for Germany. Bundesbank president Jens Weidmann opposes OMT, but this is probably nothing more than a stance for a German audience. (Opposition was stated only in German; there seems to be no English translation.)

Will southern European countries receiving aid continue to work on cutting deficits and enacting reforms? Can the European economy recover? Uncertainty about these two points is fueling skepticism. However, since these fears will not flare up again for six months to a year, they will not hinder a decline in market interest rates for the time being. Furthermore, a correction in the unusually high interest rates in southern Europe will by itself be a powerful force for an economic recovery. This is why the market will probably shift to a risk-on phase for now.

Figure 1: Spanish government bond yields (2 & 10 year) and IBEX 35

Figure 2: US 10-year government bond yield, risk premium and S&P500

Figure 3: General government financial balance as a percentage of GDP - Euro countries, US, UK and Japan

2) The rising likelihood of QE3 ? The evolving role of central banks

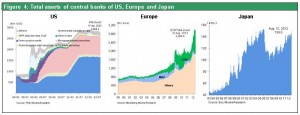

The August US employment statistics showing that 96,000 jobs were added did not meet market expectations. More monetary easing is almost certain to take place. Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke has stated that quantitative easing has produced sufficient benefits and that he is prepared to start more easing if necessary. If this happens, purchases of US Treasuries, mortgage-backed securities and other securities are likely to increase the Fed’s balance sheet to around $500 billion.

In the wake of the Lehman shock, non-traditional financial policies and quantitative easing have become the norm. There are two reasons.

(1) During a financial crisis, central banks have become the buyer of last resort instead of the lender of last resort.

(2) In the past, bank loans were the primary channel for supplying liquidity. Today, buying power can be created by raising market prices, which equates to a reduction in the risk premium.

As a result, there are worries about (1) the rapid growth in central bank assets and (2) the cost to governments resulting from growth in central bank financial assets that are vulnerable to price volatility. Should we view this as a sign of the impending corruption of central banks and promotion of the moral hazard? Or is this simply evolution? Pessimists believe it is a sign of decadence. They think that non-traditional policies have failed and the economy will face even greater difficulties. But optimists like me regard this as the evolution of central banks and believe that prospects for the success of current policies are excellent. The debate must be based on pragmatism. After the bubble burst, can a recovery in jobs take place and the economy returned to a growth trajectory or not? If this possible, the next question is what types of policies and what path is needed to achieve a recovery. To determine the answers, past textbooks and the positions of thinkers will be completely useless.

Today’s problem is caused by the inability to direct an ample supply of capital to the proper users. Correcting this problem should create demand and jobs. Officials overseeing economies of major countries must take the necessary actions. The US Fed is attempting to use surplus funds to encourage risk-taking in financial markets and the real economy. In financial markets, the aim is to use money to buy assets with risk. In the real economy, the aim is to use money to buy durable goods and investments rather than for short-term consumption.

I believe that the role of central banks is shifting. This involves a change in what stands behind the currency that these banks issue. Under the gold standard, central bank balance sheets were currencies and gold. With managed currencies, assets are balanced between currencies and government bonds. However, as the Greek crisis demonstrated, there are increasing doubts about holdings of government bonds. Before the Lehman shock, the Fed’s balance sheet was almost entirely government bonds. Afterward, the Fed added a massive amount of mortgage-backed securities and other marketable securities. This is a shift of historic proportions in the role of a central bank.

The shift in assets from gold to government bonds and then government bonds to marketable securities is very significant. The shift may currently look like nothing more than a stopgap measure to quell a crisis. But this asset structure may become permanent. When the gold standard was abandoned, this move as well was viewed as simply a stopgap measure to achieve stability quickly. At that time, most people probably thought that a central bank system of using government bonds instead of gold to back money could not last. Almost everyone expected a return to the gold standard. When the Nixon shock created the paper dollar standard, people again regarded the move as a stopgap measure to overcome a current problem. However, looking back on these events now shows that they were all the beginning of a new currency system. Perhaps we should regard the current change in the same way.

Currency systems of the past were not developed by someone based on an ideological plan. Systems changed because the markets demanded a change. The gold standard was supported by the widely embraced fantasy that gold would always have a value. Government bonds were backed by the faith of the public that governments, which have the power of taxation, will always be able to redeem the bonds. But cracks are starting to appear in this belief. So exactly what is supporting marketable securities? Marketable securities are the first form of economic value to appear in the assets of central banks. These securities represent the present value of future cash flows that can be predicted with reliability. In this sense, we can say that securities have a more solid backing than gold and government bonds. The mechanism of issuing money backed by marketable securities is just now emerging. Is this a new change? Or is this only a temporary phenomenon? No one knows. However, there is no doubt that the switch to a new currency mechanism will require the creation of new demand. Demand must keep pace with the rapid increase in productivity and the global growth in the ability to supply goods. Otherwise, there will be a strong possibility of a severe recession caused by an excess supply. In this respect, the United States may have started to implement economic policies that look ahead to the next generation.

Figure 4: Total assets of central banks of US, Europe and Japan

3) Mounting of political pressures to the BOJ and investment implications

While the US and European central banks pursue non-traditional financial policies, the incrementalism of the BOJ, which remains faithful to the textbook approach, is creating still more pressure for the yen to appreciate. The US has an aggressive stance for the stimulation of demand. But Japan has a negative stance. Differences between these two approaches are having an enormous influence on economic growth rates and the performance of stock markets.

However, QE and SM2 may ultimately induce a global stock market rally and sustained economic expansion. If this happens, the dollar would rise and the yen would fall. Speculative pressure on the yen is the symbol of risk avoidance as a crisis deepens. But this pressure would probably lessen amid rising stock prices and economic growth in the world.

Mounting pressure for the BOJ to alter its policies is attracting attention. A general election is expected to be held in Japan as soon as this fall. The ruling Democratic Party of Japan and opposition Liberal Democratic Party, Your Party, Japan Restoration Association and other parties have all started calling for more easing to start prior to the election. (1) The DPJ’s rough public promises include the government and BOJ enacting policies in concert to end deflation, BOJ purchases of overseas bonds to prevent the yen from strengthening, and other actions. (2) The LDP wants an accord between the government and BOJ to establish an inflation target (about 2%) and BOJ purchases of foreign bonds. The LDP has also announced a preliminary proposal for revisions to the BOJ Law. (3) Your Party and Japan Restoration Association continue to demand bold financial policies centered on revisions to the BOJ Law.

The BOJ will probably be forced to make a dramatic shift in its policies after the success of the US and European anti-deflation initiatives and non-traditional financial policies. This could be the last push to bring about a major reversal of the yen’s prolonged upturn. Investors should be aware of the possibility that Japan may be on the verge of a big change in direction for both its strong-yen deflation and long-term stock market slump.