(1) Will the Abe reflationary measures be implemented?

Public opinion polls indicate that Japan will choose a coalition government led by the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) on December 16. That means LDP president Shinzo Abe is very likely to be Japan’s next prime minister. Financial markets are most interested in whether or not Japan can implement the reflationary measures backed by Mr. Abe. Enactment of these measures would probably produce a big surprise in the direction of financial markets. Mr. Abe wants to enact extremely bold reflationary measures. He wants to (1) establish an inflation target of 2% to 3%, (2) use the Bank of Japan to purchase large amounts of Japanese government bonds, (3) amend the Bank of Japan Law so that the bank is responsible not only for inflation but also for the economy and employment, and (4) increase public-works expenditures. Criticism is intense because these measures go against the conventional thinking of Japanese economists and are inconsistent with the Bank of Japan’s own stance. As a result, many people think that Mr. Abe will be unable to enact these policies.

Most economic experts and members of the media back the current stance of the Bank of Japan, which can be summed up as “the belief that deflation is unavoidable.” This includes the beliefs that (1) structural reforms are needed to end deflation (a point that has been repeated for many years that has not yet been achieved), (2) deflation and the oversupply of goods are historic global trends, (3) monetary easing has already reached the limit and can go no farther, and (4) pressure on the Bank of Japan will lead to hyper-inflation. This “deflation war defeatism” may create a barrier that prevents the enactment of Mr. Abe’s proposed reflationary measures. Expectations for the enactment of these measures in late November when the general election was announced caused the yen to drop and stock prices to rise. But these two movements ran out of steam in December. The reason is probably that investors doubt that the Abe reflationary measures can be enacted.

Power centers support the Abe reflationary measures

However, the view of financial markets is probably mistaken. The reason is that the Ministry of Finance and United States, which are the real powers behind this issue, will most likely support reflationary measures. The Ministry of Finance wants very much to have a strong economy in Japan prior to the 2014 consumption tax hike. The United States needs to have Japan heighten its stature as part of the U.S. strategy regarding China. The United States has come to realize that the strong yen is what has pushed Japanese electronics makers, crucial business partners to U.S. high-tech players, to the brink of bankruptcy and will thus probably allow a correction to lower the yen’s value. Above all, though, Japanese voters want very much to end deflation and turn around the economy. As a result, the Japanese public will probably ignore the ‘list of impossibilities’ espoused by the Bank of Japan, the academic community and the media. This is why implementation of the Abe reflationary measures, which are viewed with skepticism by financial markets, may spark the positive surprise of a big downturn of the yen and upturn in stock prices.

(2) The sharp contrast between the Japanese and U.S. economies over the past 80 years

After the Lehman shock, the U.S. rebounded while Japan slumped

The Lehman shock and the Great Depression of the 1930s are similar in many ways. Both involved the bursting of an asset bubble that temporarily destroyed the financial system. The world came to the brink of economic collapse in both cases. But events that followed these two events are entirely different. In the 1930s, there was a dramatic contraction in economic activity and deflation took hold. This led to the tragedies of international confrontations and eventually a world war. After the Lehman shock of 2008, credit was restored and economic activity returned to the pre-crisis level. There has been steady progress with eliminating the after-effects of this crisis. Creative monetary easing measures overseen by Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke probably rescued the United States from the financial crisis. Today, there is virtually no danger of the United States suffering an economic downturn on the scale of a Great Depression. However, this applies only to the United States.

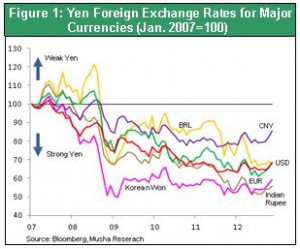

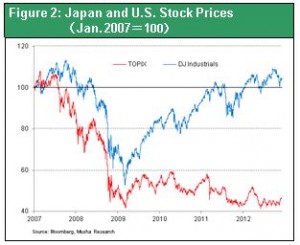

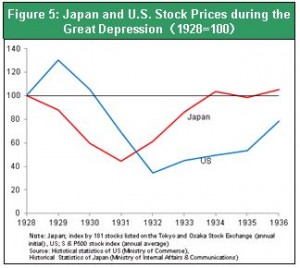

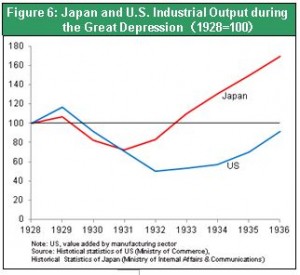

After the Lehman shock, there have been significant differences between the Japan and other major countries in terms of stock prices, foreign exchange rates, inflation and manufacturing. Economies recovered steadily in the United States and other major countries while Japan conspicuously fell behind. There was a peculiar slump in Japanese stocks while the yen alone strengthened among major currencies and Japan alone suffered from deflation. As you can see in Figure 1, the yen appreciated remarkably in relation to other major currencies of the world. Since the beginning of 2007, the yen appreciated 50% against the Korean won and 30% against the U.S. dollar and euro. The yen’s strength severely eroded the competitive edge of Japanese manufacturers. The backdrop for these events is probably the Bank of Japan’s negative stance regarding monetary easing, which was one reason that the yen alone appreciated among major currencies. Figure 2 shows how much stock markets have rebounded from the lowest points after the Lehman shock. As you can see, U.S. and German stock prices have doubled. In Japan, stock prices have recovered only 10%, far less than in the United States and Europe where the financial crisis originated. Furthermore, Figure 3 shows that Japan has also fallen far behind in terms of manufacturing. As I will explain later, this is the result of the following cause-and-effect progression: change in currency (exchange rate) = change in stock prices = change in manufacturing output.

Figure 1 Yen Foreign Exchange Rates for Major Currencies

Figure 2 Japan and U.S. Stock Prices

Figure 3 Japan and U.S. Production Indexes

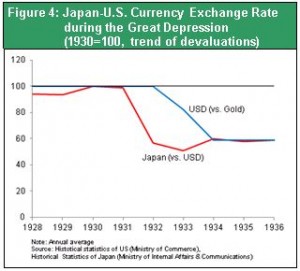

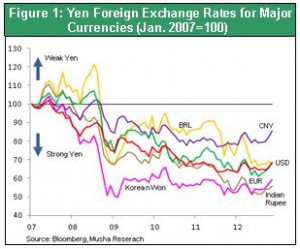

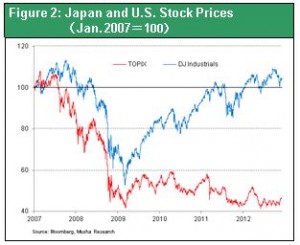

80 years ago Japan enacted reflationary measures while the U.S. embraced liquidationism

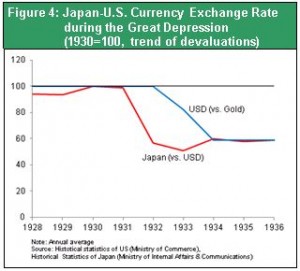

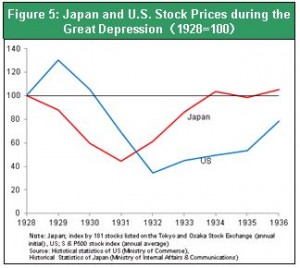

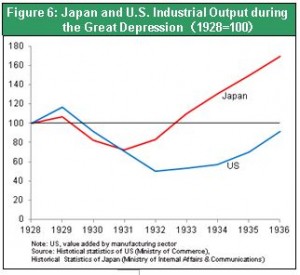

Countries of the world are competing to determine the best policies. Wise countries can secure advantageous positions for their economies and markets. In the 1930s, Takahashi reflation (ending the gold standard and adopting a managed currency system, guiding the yen downward, using the Bank of Japan to underwrite government bonds) made Japan one of the first countries to abandon 'liquidationism and shift to policies that target demand. Around the time the Great Depression began in 1929, the world’s major countries began to return to the gold standard. Somewhat afterward, Japanese Minster of Finance Junnosuke Inoue lifted Japan’s gold embargo (1930). Adopting tight fiscal and monetary policy in the midst of the Great Depression sent Japan into a deep economic downturn (an act similar to opening shutters at the peak of a storm). Nevertheless, Japan’s economy and stock market were first in the world to start recovering due to the Takahashi reflationary initiatives (beginning in December 1931), which were Keynesian measures prior to the birth of Keynesian economics. In the United States, there was a delay in the shift from the Hoover administration’s liquidationism to the demand-linked policies of the Roosevelt administration (starting in 1933). As a result, the United States suffered more than any other country from the global recession. A big reason for Japan’s actions was the support for aggressive reflationary measures by economists Tanzan Ishibashi, the leader of Toyo Keizai, Kamekichi Takahashi and Toshie Obama, all of whom played a prominent role in Japan’s postwar economy. Some individuals at the Bank of Japan, including deputy governor Eigo Fukai, were opposed to the fiscal tightening of Finance Minister Inoue. These same individuals subsequently became the brain power behind the Takahashi reflationary initiatives. As a result, even as the United States became mired in a deep depression, Japanese stocks doubled as Japan staged a V-shaped recovery. Real estate prices in Japan increased, too. The Japanese economy remained strong until 1936, when Finance Minister Takahashi was assassinated during the February 26 incident, an attempted coup d’etat by the military. Clearly, Japan was ahead of the United States in terms of its policies and economic recovery at that time due to the cause-and-effect progression noted earlier in this report: change in currency (exchange rate) = change in stock prices = change in manufacturing output

Table 4 Japan-U.S. Currency Exchange Rate during the Great Depression (Devaluations)

Table 5 Japan and U.S. Stock Prices during the Great Depression

Table 6 Japan and U.S. Industrial Output during the Great Depression

Today, there are concerns about the Bank of Japan underwriting government bonds. We need to examine the time of Finance Minister Takahashi (using government spending to create demand) and the period after this time. Government bond purchases by the Bank of Japan were used as a means of increasing military expenditures, which Finance Minister Takahashi opposed. But this led to hyperinflation that could not be stopped. However, prior to this hyperinflation, bond purchases by the Bank of Japan were an effective means to creating demand that fueled an economic recovery.

This time, the United States was first to shift its policies rather than last as in the 1930s. Japan, which was first to change direction in the 1930s, has been the greatest laggard in altering its economic policies. The reflationary policies proposed by Shinzo Abe are reminiscent of the Takahashi reflationary measures in Japan’s prewar days. Today, Japan has reached a critical point in determining whether or not these policies will be enacted.

Today, there are concerns about the Bank of Japan underwriting government bonds. We need to examine the time of Finance Minister Takahashi (using government spending to create demand) and the period after this time. Government bond purchases by the Bank of Japan were used as a means of increasing military expenditures, which Finance Minister Takahashi opposed. But this led to hyperinflation that could not be stopped. However, prior to this hyperinflation, bond purchases by the Bank of Japan were an effective means to creating demand that fueled an economic recovery.

This time, the United States was first to shift its policies rather than last as in the 1930s. Japan, which was first to change direction in the 1930s, has been the greatest laggard in altering its economic policies. The reflationary policies proposed by Shinzo Abe are reminiscent of the Takahashi reflationary measures in Japan’s prewar days. Today, Japan has reached a critical point in determining whether or not these policies will be enacted.

Today, there are concerns about the Bank of Japan underwriting government bonds. We need to examine the time of Finance Minister Takahashi (using government spending to create demand) and the period after this time. Government bond purchases by the Bank of Japan were used as a means of increasing military expenditures, which Finance Minister Takahashi opposed. But this led to hyperinflation that could not be stopped. However, prior to this hyperinflation, bond purchases by the Bank of Japan were an effective means to creating demand that fueled an economic recovery.

This time, the United States was first to shift its policies rather than last as in the 1930s. Japan, which was first to change direction in the 1930s, has been the greatest laggard in altering its economic policies. The reflationary policies proposed by Shinzo Abe are reminiscent of the Takahashi reflationary measures in Japan’s prewar days. Today, Japan has reached a critical point in determining whether or not these policies will be enacted.