Feb 22, 2021

Strategy Bulletin Vol.274

Japanese stocks have begun to correct from their "irrational pessimism"

- The Nikkei 225 is on a straight line to 40,000, and there won't be much pushback

The breathtaking surge in stock prices continues. The Nikkei 225 index reached 30,000 yen for the first time in 30 years, since the collapse of the bubble economy. Since the beginning of this year (until February 19), Japanese stocks (Nikkei 225) have risen 8.8%, the highest among developed countries, much higher than the US (SP500) at 3.8% and Europe (STOX600) at 3.2%. This performance is comparable to the 8.1% of the KOSPI in South Korea and 11.0% of the TAIEX in Taiwan, the two major semiconductor powerhouses that are fully benefiting from the global semiconductor boom. The stock bubble theory is in full swing, with the Yomiuri Shimbun and Mainichi Shimbun running daily columns and editorials criticizing the stock bubble. But this is a mistake. The media and experts should take responsibility for the quality of their words and not just leave it at that. The biggest risk for investors in 2021 will be the "risk of not holding" and not the "risk of falling asset prices," which is the same as last year.

(1) Correction of the "negative bubble" that has taken root only in Japan

The true nature of irrational pessimism

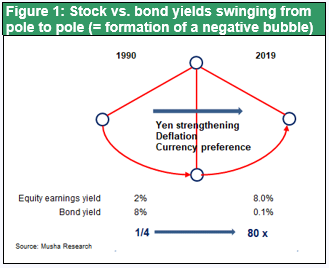

It is noteworthy that the correction of "irrational pessimism" has begun in Japanese stocks. Over the past 30 years, the NY Dow has increased tenfold, from $3,000 to $30,000. However, Japanese stocks (Nikkei 225) have been completely flat at 30,000 yen, an extreme underperformance of one-tenth. This one-tenth can be broken down with half attributed to the correction of the abnormal price bubble, but the other half is attributed to a negative bubble. In 1990, when deposit rates and bond yields were 8%, dividend yields were 0.5% and stock yields were 2% (PER 50x), with stocks clearly in a bubble. In 2019, the year immediately before Covid-19, when deposit rates and government bond yields were 0%, dividend yields were 2% and stock yields were 8% (PER 13x), obviously in a "negative bubble”.

Irrational pessimism: (1) "negative bubble”

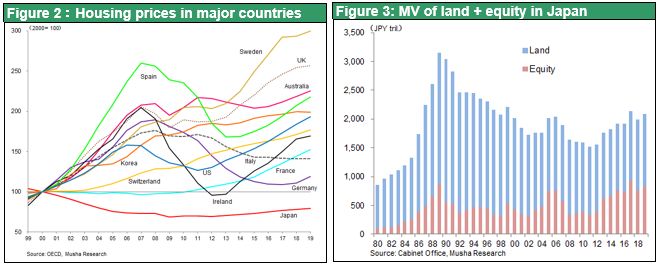

Irrational pessimism has seeped into Japanese stocks during the “lost” 30 years. The false belief that Japan is a special country incapable of growth (on the pretext of its declining birthrate, aging population, and staggering budget deficit) has taken root in academia and the media. There is now a movement to correct two forms of "irrational pessimism": (1) an abnormally undervalued stock valuation "negative bubble" and (2) an extremely risk-averse portfolio of financial assets. A stock bubble is a situation in which stock prices are far from their intrinsic value, which will eventually be corrected by a sudden change in market prices. There are two types of bubbles. The first type is usually a bubble in which prices rise too much, but in Japan a "negative bubble" in which prices fall too much has taken root. As shown in Figure 2, stock and housing bubbles have ballooned then burst not only in Japan but also across the whole world, However, in most other countries, asset prices have subsequently returned to their pre-bubble levels. Japan is the only country where asset prices have not recovered after the bubble burst, with the excessive decline of a “negative bubble” taking root. Figure 3 shows the value of assets in Japan (land plus market value of stocks), which was 3,142 trillion yen in 1989. This value halved to 1,512 trillion yen by 2011 due to the excessive fall of land and stock prices, creating a severe burden for companies, banks and households. There is now a movement to correct this excessive price decline.

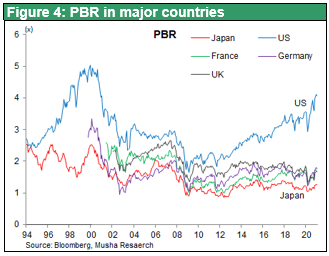

As a result, valuations of Japanese stocks are among the lowest in the developed world. A comparison of the P/B ratios of various countries shows that Japan is extremely undervalued, with the US at 4.1 times, the UK, Germany and France at 1.7 times, and Japan at 1.2 times. If only this were corrected to the level of Europe, Japanese stocks would rise by 40%. If corrected to 2 times, half the level of the US, Japanese stock prices would soar by 80%. We believe that the correction of this "negative bubble," which is unique to Japan, has now begun.

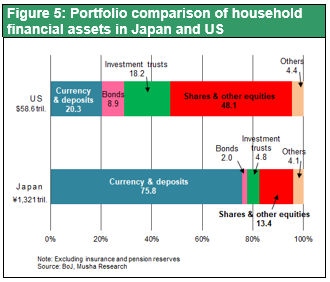

Irrational pessimism: (2) extreme risk-averse portfolio with worst performance

An extreme bias toward holding so-called safe assets (cash, deposits, and bonds) has taken hold in the financial asset portfolios of Japanese households and institutional investors. For example, a comparison between Japan and the US of the composition of financial assets that households have at their disposal (total assets minus pension insurance reserves) shows that in the US, 66% are stocks and investment trusts and 29% are cash, deposits, and bonds, while in Japan, 78% are cash, deposits, and bonds and 18% are stock investment trusts, meaning households are extremely risk averse. Stocks are anticipated to have virtually 2% returns and rise (due to profit growth), but since interest rate are anticipated to rise in future (= loss due to decline in price) because the interest rate on cash and deposit is zero and interest rates on bonds are zero, it must be said that such Japanese portfolios are dominated by "irrational pessimism”. With the Nikkei average having quadrupled in the past 10 years and doubled in the past year, a raging shift of funds from "safe assets" to stocks is inevitable. If the current rally in Japanese stocks is a correction of such "irrational pessimism," the rally will not face much pushback. There will be a straight correction.

(2) The fundamental fallacy of the stock bubble theory

It is time for pessimists to remove their colored glasses. The long period of deflation and economic stagnation has made Japanese investors accustomed to colored glasses tinted with pessimism. However, if they do not change their minds quickly, they may suffer investment losses. In particular, the following three assumptions should be abandoned: (1) rising asset prices will eventually be punished by the bursting of bubbles, (2) monetary easing and fiscal stimulus are bad policies that will leave the bill behind, and (3) the future of Japan is bleak with a declining birthrate and aging population.

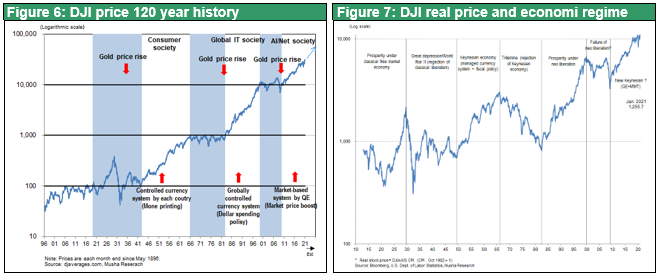

Pessimism fallacy: (1) Rising inflation and interest rates will not cause a stock market crash

There is a persistent argument in the US that high inflation and rising long-term interest rates will cause the stock market bubble to burst. Economists in the mainstream share the view that integrated fiscal and monetary easing will fail because it will result in inflation or government bankruptcy. There is also an argument in the US that higher interest rates will cause stock prices to collapse. We believe this argument is false for two reasons. First, inflation itself depresses the value of real assets such as stocks. It also depreciates the government's real debt. This is exactly what happened in the US in the 1970s (nominal stock prices were flat between 1967 and 1982, but real stock prices depreciated by one-third in 15 years due to 7% annual inflation). Inflation does not cause stock price crashes. Comparing the nominal value of the US NY Dow (Figure 6) with the real value of the NY Dow (Figure 7), we can see how inflation has caused a peaceful depreciation of asset prices without significantly damaging economic confidence.

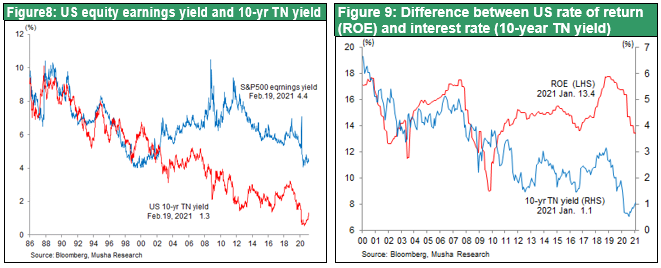

Pessimism fallacy: (2) Rising interest rates will restore the arbitrage function of financial markets

Second, until 2000, the yield on US stocks (SP500) and the yield on 10-year Treasuries were almost at the same level and linked to each other (Figure 8). There was a clear arbitrage between stocks and bonds. However, since 2000, while yields on government bonds have fallen, yields on stocks have remained high, and the gap between the two has widened, meaning that arbitrage investment has disappeared and investors' preference for bonds (i.e., risk aversion) has taken root. This divergence has become even more serious since the Global Financial Crisis. In other words, stocks have become undervalued relative to bonds. The risk of a surplus of savings, zero interest rates, and deflation (known in the West as Japanification) was rising. The expected process of fiscal stimulus -> higher expected inflation -> higher long-term interest rates (i.e., lower bond prices) would restore arbitrage between stocks and bonds, thereby activating and normalizing financial and capital markets. The correction of overvalued bond prices is inevitable, but the argument that this will lead to a decline in stock prices is clearly unreasonable.

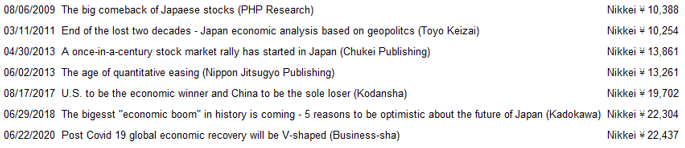

(3) The correctness of Musha Research's consistent optimism

The criticism of "irrational pessimism" over Japanese stocks has been the sole argument of Musha Research for the past 10 years. How and when Musha Research has made this claim is clear from the following works and the stock prices at the time of writing.

In addition to the above works, Musha Research has posted all of its reports for the past 12 years on its website (https://www.musha.co.jp/).